A briefing paper prepared by Daniel L. Carlson (University of Utah), Richard J. Petts (Ball State University), and Joanna R. Pepin (University of Buffalo – SUNY) for the Council on Contemporary Families.

For the past 30 years the gender revolution has proceeded at a snail’s pace. Some argue it has actually stalled. Relationship quality and stability now appear greatest when heterosexual partners are equals, and some evidence shows that couples are increasingly likely to share domestic labor. Yet the proportion of couples who achieve egalitarian arrangements remains low relative to the proportion of adults who value gender equality. And now, as the COVID-19 pandemic rages, some fear the gains of the gender revolution will be erased. Recent surveys commissioned by the New York Times and USA Today appear to confirm such fears, suggesting that during the pandemic women continue to shoulder the majority of housework and childcare, and now also do the majority of homeschooling too, despite men’s claims to the contrary.

These polls, however, omit one very important thing – how families were arranging domestic labor prior to the pandemic. A focus on homeschooling as an emergent and pressing issue is understandable, given the way this task may exacerbate inequalities at home. But how partners divide the responsibilities for educating their children during the pandemic may tell us little about the future of gender equality once the pandemic ends, since homeschooling is temporary for most parents. When we examine trends in the division of those housework and childcare tasks that have been in the process of renegotiation for decades, the patterns provide evidence of more egalitarian progress.

A glass half full or half empty? Most women still do more at home than men, but many men are doing more than before the pandemic — and very few (if any) are doing less

Our survey[i], an online non-probability sample of parents (n = 1,060) in different-sex couples, conducted in mid-April, assessed divisions of labor during the pandemic and compared them to how couples divided labor before it began. Our results[ii] suggest a more hopeful scenario than those implied by the headlines: According to both men and women, men are doing more housework and childcare during the pandemic than before it began, leading to more equal sharing of domestic labor. Moreover, given the conditions under which men are doing more, there is potential that these changes may persist after the pandemic ends.

Though homeschooling falls largely on the shoulders of women, our results indicate that for the majority of men and women (approximately 60 percent), time in domestic labor has not changed since the beginning of the pandemic, even accounting for helping children with homework. This is because time in some tasks like transporting children, attending children’s events, organizing children’s schedules/activities, and grocery shopping (for women, at least) have declined dramatically or stopped altogether.

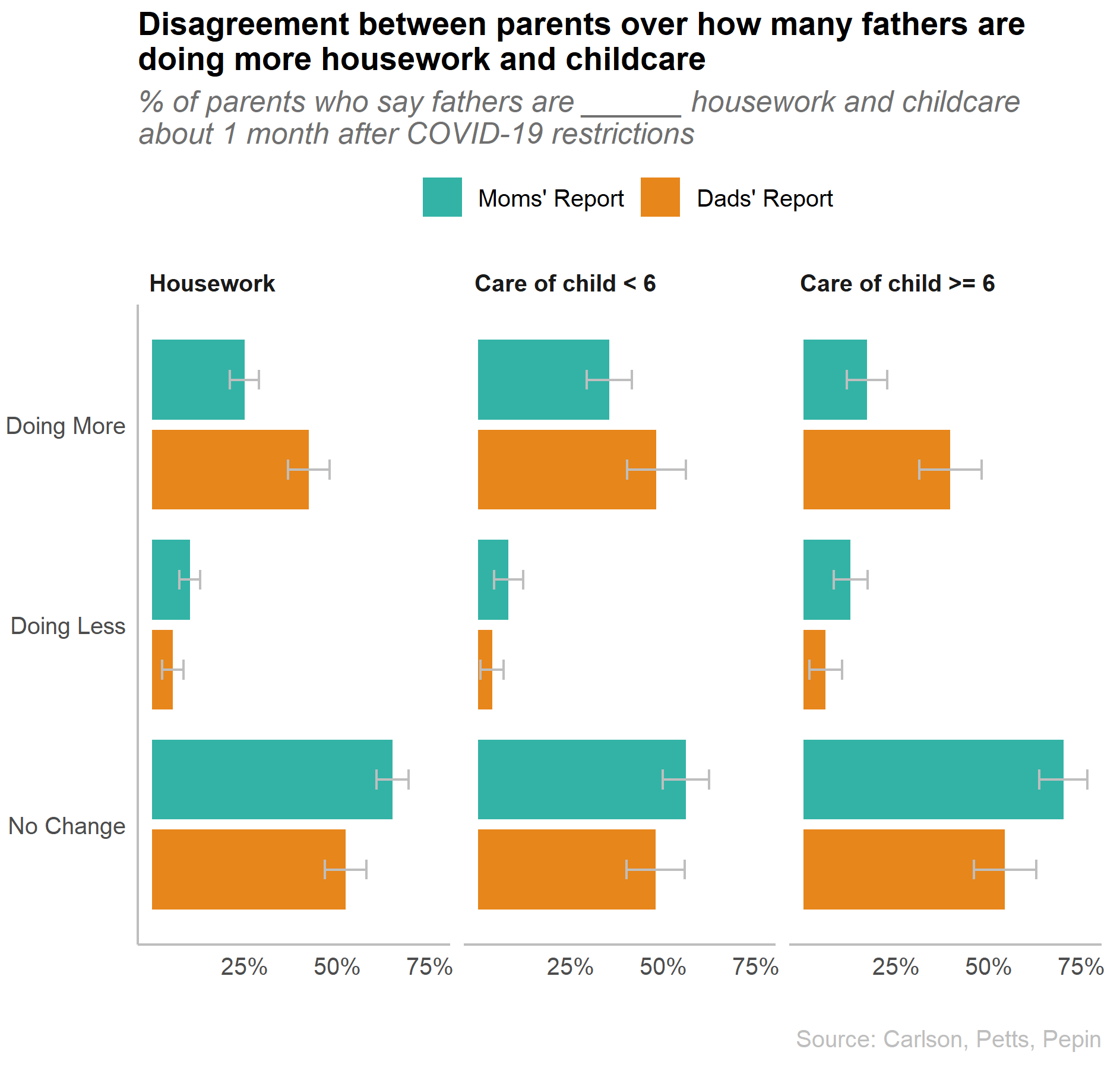

Men and women differ in their reports of who does more domestic work; the truth is likely somewhere in the middle.

One of the most provocative findings in the NYT and USA Today surveys is the discrepancy between men’s and women’s reports of who is doing what in the household. For example, in the NYT story, 80 percent of women report doing the majority of homeschooling right now. Yet 45 percent of men also claim to be doing most of the schooling, while only three percent of women report their male partners as the primary educator. Like the Times, we find that most women (70 percent) report being primarily responsible for homeschooling during the pandemic, but we find a much smaller gender gap in men’s and women’s assessments of men’s responsibilities for schooling: 20 percent of men say they are doing the online educating while three percent of women say their male partners are largely responsible. Discrepancies between the estimates in the two studies may be the result of sampling variation or differences in question wording – the NYT asked about homeschooling children or helping with distance learning – that may influence responses.

Men and women also differ in their reports of how much housework and childcare each is doing, although the differences are not as large as over the homeschooling question. The NYT story suggests that men’s estimates are more accurate than women’s. But it is not at all clear that men exaggerate their time use more than women in surveys or fail to notice their partners’ time use more than women do (Bianchi et al. 2000; Kamo 2000; Lee and Waite 2005; Yavorksy, Kamp-Dush, and Schoppe-Sullivan 2015). In an appendix to this report, we discuss why we use both men’s and women’s reports to construct estimates of the division of domestic labor during the COVID-19 pandemic – an approach we argue is ultimately conservative. Nonetheless, even if we rely only on women’s reports, the story from our data on how the pandemic has changed domestic labor is the same: Men are doing more housework and childcare since the pandemic began, and this has led to an increase in egalitarian domestic arrangements.

When we focus on the housework and childcare tasks that couples were dividing before the pandemic, we find that among couples where the division of tasks has changed, it has changed in an egalitarian direction. Indeed, in no situation — and in no type of family, whether dual-earner where both are working full-time, dual-earner where someone is working part-time, single earner, or both unemployed — did we find that the division of tasks became less likely to be shared.

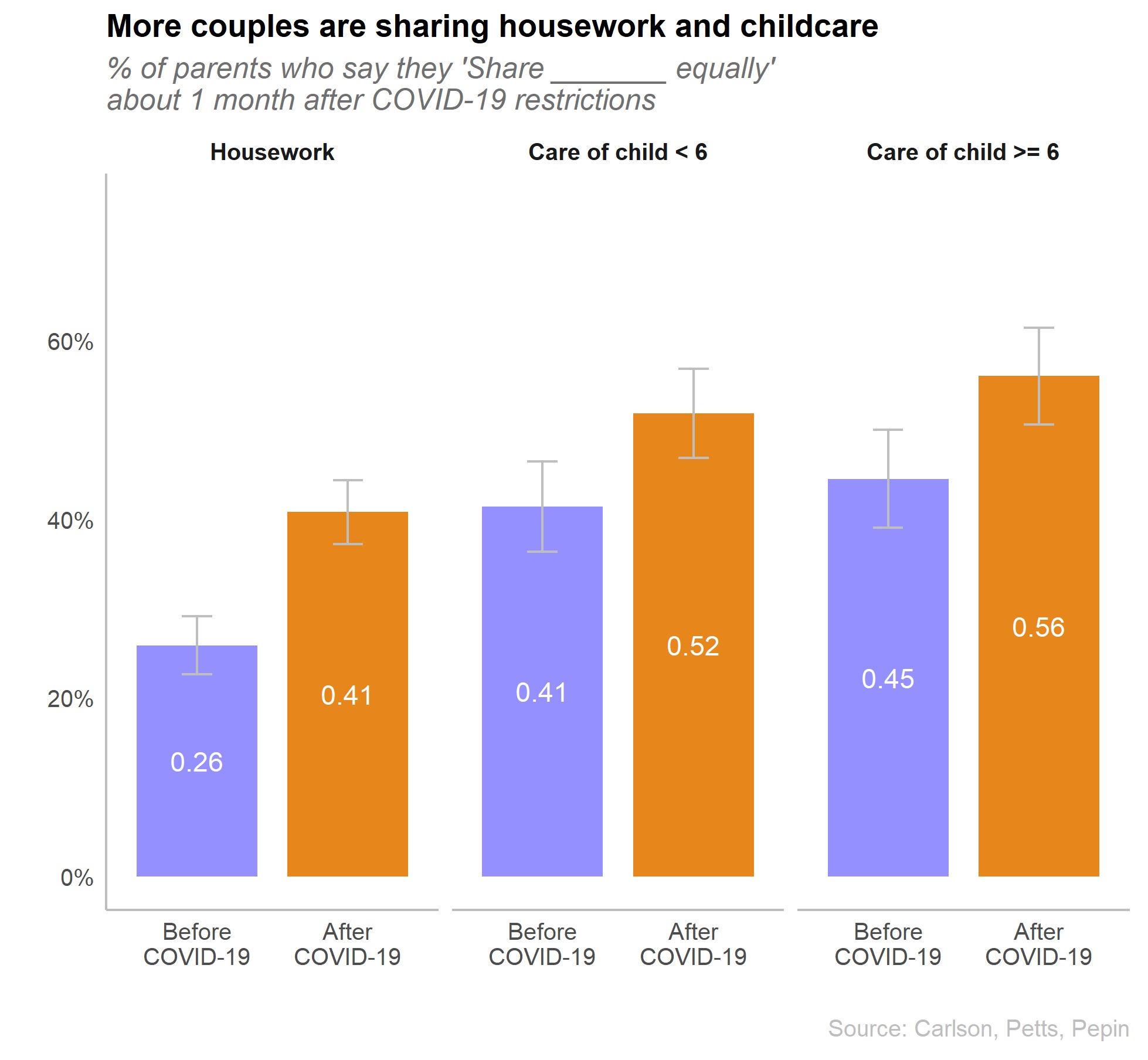

Considering both men’s and women’s reports, we see that prior to the start of the pandemic, 26 percent of parents reported sharing routine housework[iii] relatively equally[iv] with their partner, 41 percent reported sharing care for young children[v] relatively equally – although physical childcare and the mental load of organizing children’s lives were by and large mother’s responsibilities — and 45 percent reported sharing care of older children[vi]. A little more than a month after the start of the pandemic, 41 percent of parents reported sharing housework with their partners – a significant 58 percent increase — while the percentage of partnered parents reporting equal sharing care of young and older children also increased significantly, to 52 percent and 56 percent respectively. The proportion sharing in the care of young and older children grew by 27 and 24 percent respectively, driven by increases in equal sharing of physical care, monitoring, reading, and organizing children’s activities.

We find similar evidence of change when we restrict analyses to women’s reports only. Only one-in-six women (16 percent) reported sharing housework with their partners prior to the pandemic, compared with more than one-in-four (27 percent) who reported sharing it during the pandemic. As for childcare, 28 percent of women reported sharing care of young children relatively equally prior to the pandemic while 34 percent reported sharing it equally during. For older children, women’s reports of equal sharing grew from 29 percent to 42 percent.

The increase in egalitarian arrangements is largely the product of men’s doing more. Forty-two percent of fathers reported an overall increase in housework time, 45 percent reported more time in the care of young children overall, and 43 percent reported more total care of older children. Many mothers also reported that their partners increased their total time in housework (25 percent), care of young children (34 percent), and care of older children (20 percent). Nonetheless, mothers are significantly less likely than fathers to report that fathers have increased their time in housework or childcare. Men and women who report that fathers increased their time in housework and childcare also widely report that they were sharing housework (69 percent) and childcare (76 percent) responsibilities equally with their partner during the pandemic or that the men were doing the majority.

Consistent with past research (Kamo 2000; Lee and Waite 2005), though men and women disagree on men’s time, there was no such disagreement regarding mother’s time. More than one-quarter of both fathers and mothers reported an increase in mothers’ time in housework and childcare. The women most likely to increase their time in childcare and housework were the ones who were already responsible for the majority of such work before the pandemic. Parents also agree that between 11-16 percent of mothers and 6-8 percent of fathers decreased their overall time in domestic work. This might be because some tasks are just currently obsolete.

We still don’t have an egalitarian utopia

Families are sharing domestic labor more equally since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. That is not to say, however, that the pandemic has created an egalitarian utopia in households. Indeed, although conventionally gendered divisions of housework and childcare have become less common since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many mothers continue to find themselves in these arrangements. Of the mothers who continued to be primarily responsible for domestic work during the COVID-19 pandemic, roughly one-third increased their time spent in housework and care of children during the pandemic. Moreover, 70 percent are also solely responsible for educating their children. Consequently, among families that have not moved toward more egalitarianism, domestic work for mothers has become even more time-intensive.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted every aspect of Americans’ daily lives. Stay-at-home orders in nearly every state, along with the closure of schools, childcare centers, and non-essential businesses, have placed immense strain on families, suspending important care supports and demolishing barriers between work and family roles. Our findings demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic has both exacerbated and reduced gender inequalities in the division of domestic labor. For women who continued to shoulder domestic work during the pandemic, housework and childcare responsibilities have become much more arduous. Not only are these women spending more time in classic tasks, but homeschooling has also been added to their plates. Nonetheless, though roughly half of women are doing most of the housework and childcare right now, according to our estimates another half of women are not. Among a sizeable number of families, the burden of domestic responsibilities has become more equal as fathers have increased their contributions to housework and childcare.

Will the trend towards egalitarianism last beyond the crisis?

A central question is whether fathers will continue their domestic contributions once the pandemic passes. The signs, we think, are encouraging. Research shows that many couples fail to craft egalitarian divisions of household labor in part due to unsupportive workplace-family policies (Pedulla and Thébaud 2015). The COVID-19 pandemic has eliminated some of the structural barriers to sharing domestic work – particularly for men – since many adults are now working from home. The pandemic has demonstrated that many jobs can be done remotely. To the extent such arrangements increase, this may create greater egalitarianism, because recent evidence from before the pandemic shows that men who work from home share more equally in domestic labor (Carlson, Petts, and Pepin 2020). However, whether men and women will continue to have schedule flexibility or the ability to work from home as employers re-open is unknown.

Nonetheless, just the experience of having heightened responsibilities for housework and childcare during this time bodes well for men’s continued involvement in housework and childcare. As research on paternity leave demonstrates, men who take leave, especially extensive leave (e.g., two months), continue their involvement in housework and childcare over the long-term even after returning to work (Petts and Knoester 2018; Bünning 2015). The longer the pandemic lasts, the more hardships most of us will experience. But perhaps in the aftermath the patterns of domestic involvement men are establishing now will become a new normal.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT:

Daniel L. Carlson / Associate Professor / Department of Family and Consumer Studies / University of Utah / daniel.carlson@fcs.utah.edu.

Richard J. Petts / Professor / Department of Sociology / Ball State University / rjpetts@bsu.edu.

Joanna Pepin / Assistant Professor / Department of Sociology / University at Buffalo (SUNY) / jpepin@buffalo.edu

LINKS AND ABOUT:

Report: https://sites.utexas.edu/contemporaryfamilies/2020/05/20/covid-couples-division-of-labor/

Press Advisory: https://sites.utexas.edu/contemporaryfamilies/2020/05/20/covid-couples-division-of-labor-advisory/

The Council on Contemporary Families, based at the University of Texas-Austin, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization of family researchers and practitioners that seeks to further a national understanding of how America’s families are changing and what is known about the strengths and weaknesses of different family forms and various family interventions.

The Council helps keep journalists informed of notable work on family-related issues via the CCF Network. To join the CCF Network, or for further media assistance, please contact Stephanie Coontz, Director of Research and Public Education, at coontzs@msn.com, cell 360-556-9223.

Follow us! @CCF_Families and https://www.facebook.com/contemporaryfamilies

Read our blog CCF @ The Society Pages – https://thesocietypages.org/ccf/

REFERENCES

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79(1), 191-228.

Bünning, M. (2015). What happens after the ‘daddy months’? Fathers’ involvement in paid work, childcare, and housework after taking parental leave in Germany. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 738-748.

Carlson, D. L., Petts, R. J., & Pepin, J. (2020). Flexplace Work and Partnered Fathers’ Time in Housework and Childcare. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/jm2yu/

Kamo, Y. (2000). “He said, she said”: Assessing discrepancies in husbands’ and wives’ reports on the division of household labor. Social Science Research, 29(4), 459-476.

Lee, Y.S., & Waite, L. J. (2005). Husbands’ and wives’ time spent on housework: A comparison of measures. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 328-336.

Milkie, M.A., Bianchi, S.M., Mattingly, M.J. et al. (2002). Gendered division of childrearing: Ideals, realities, and the relationship to parental well-being. Sex Roles, 47, 21–38.

Pedulla, D. S., & Thébaud, S. (2015). Can we finish the revolution? Gender, work-family ideals, and institutional constraint. American Sociological Review, 80(1), 116-139.

Petts, R. J., & Knoester, C. (2018). Paternity leave‐taking and father engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1144-1162.

Press, J. E., & Townsley, E. (1998). Wives’ and husbands’ housework reporting: Gender, class, and social desirability. Gender & Society, 12(2), 188-218.

Scarborough, W. J., Sin, R., & Risman, B. (2019). Attitudes and the stalled gender revolution: Egalitarianism, traditionalism, and ambivalence from 1977 through 2016. Gender & Society, 33(2), 173-200.

Yavorsky, J. E., Kamp Dush, C. M., & Schoppe‐Sullivan, S. J. (2015). The production of inequality: The gender division of labor across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(3), 662-679.

APPENDIX

Early analyses using data from the 1980s found that although men and women both overestimate their time in housework in surveys compared to time diaries, men were more likely to overestimate their time than women (Press and Townsley 1998). And new fathers in dual earning couples also appear to overestimate their housework time more than new mothers (Yavorsky, Kamp-Dush, and Schoppe-Sullivan 2015). But numerous other studies comparing time diary and survey data on men’s and women’s time use indicate that men and women equally overestimate their own time in housework in surveys (Bianchi et al. 2000; Lee and Waite 2005; Yavorsky, Kamp-Dush, and Schoppe-Sullivan 2015). According to Bianchi et al. (2000) and Yavorsky and colleagues (2015), men and women overestimate their own time in housework in surveys both by approximately 50 percent. This applies to men and women generally, including married men and women and childless men and women in dual-earning couples. The study by Yavorsky and colleagues is the only one that we are aware of that compares men and women’s estimates of time in childcare between time diary and survey data, and even then, it only evaluated physical childcare amongst new parents in dual-earning couples. These researchers found that new mothers appear to overestimate their time in childcare more than new fathers. Whether these patterns hold for non-physical childcare, older children, and parents in single-earning couples is unclear.

When estimating one’s partner’s time, research shows that men and women disagree over men’s time use, but generally agree on women’s time use (Kamo 2000; Lee and Waite, 2005). In US based samples, men report more time in domestic labor than women report of their male partners (Kamo 2000; Lee and Waite, 2005; Milkie et al 2002). In surveys, men overestimate their female partners’ time, while women’s estimates of men’s time are generally consistent with men’s time use gathered using time diaries (Lee and Waite, 2005).

The tendency of women to overestimate their own time, but not their partners’ time, may lead to an underestimation of men’s shares of domestic labor in surveys (Lee and Waite 2005). Though men’s reports of time use are less accurate in terms of absolute amounts, their tendency to overestimate both their own and their partners’ time use appears to result in more valid estimates of partners’ shares of domestic labor. When using survey data, accordingly, estimates of relative shares of domestic labor may give a more accurate picture of couple dynamics than estimates of each partners’ absolute time in tasks (Kamo 2000). Using both men’s and women’s reports of men’s shares of domestic tasks is therefore a conservative approach to estimating the division of domestic labor from survey data.

[i] Participants for this study completed a Qualtrics questionnaire and were recruited from Prolific (www.prolific.co). Prolific is an opt-in online survey panel similar to Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk). The sample consisted of parents who reside with a spouse/partner, with an oversample of men, black, non-college educated, and ideologically conservative respondents to approximate national demographics. The sample included an additional n = 86 same-sex partners who are not included in this analysis. [ii] Results have been weighted using estimates from the 2019 Current Population Survey to be representative of American parents who reside with a child under the age of 18 based on parent’s gender, age, and race/ethnicity. Because our sample is a non-probability sample results still may not be representative of the United States population despite weighting. [iii] Routine housework includes cooking meals, doing dishes, house cleaning, laundry, and grocery shopping [iv] Relatively equal is defined as men doing between 40 percent and 60 percent of labor. Findings regarding patterns of change are similar when a 35/65 split is used. [v] For parents of young children (less than age 6) tasks include: physical care; talking to children; looking after children; reading to children; putting children to bed; playing with children; organizing children’s lives/activities; enforcing rules. [vi] For parents of older children (age 6 to 17) tasks include; talking to children; monitoring children’s whereabouts; attending children’s events; reading with children; playing with children; organizing children’s lives/activities; enforcing rules; picking up/dropping off children up; helping children with homework.