A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families by Renee Ryberg, Child Trends, and Arielle Kuperberg, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

April 2, 2025

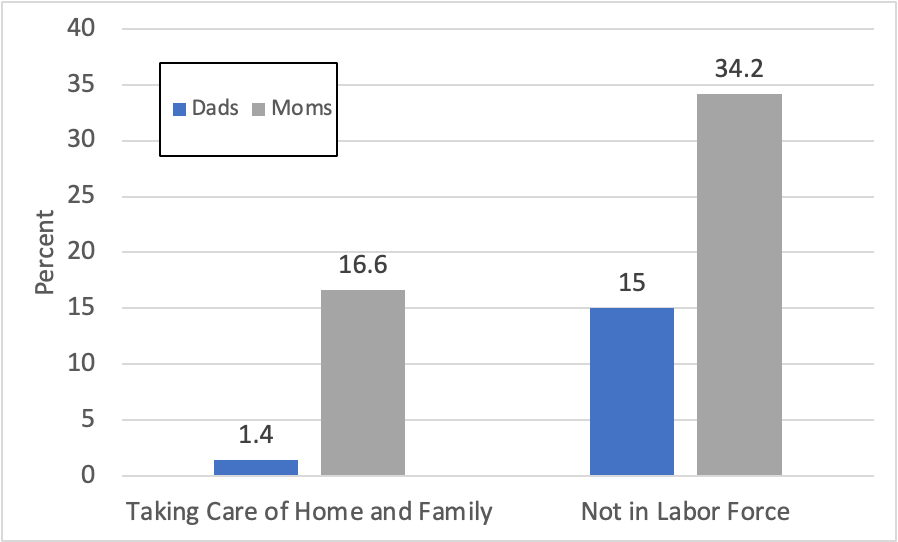

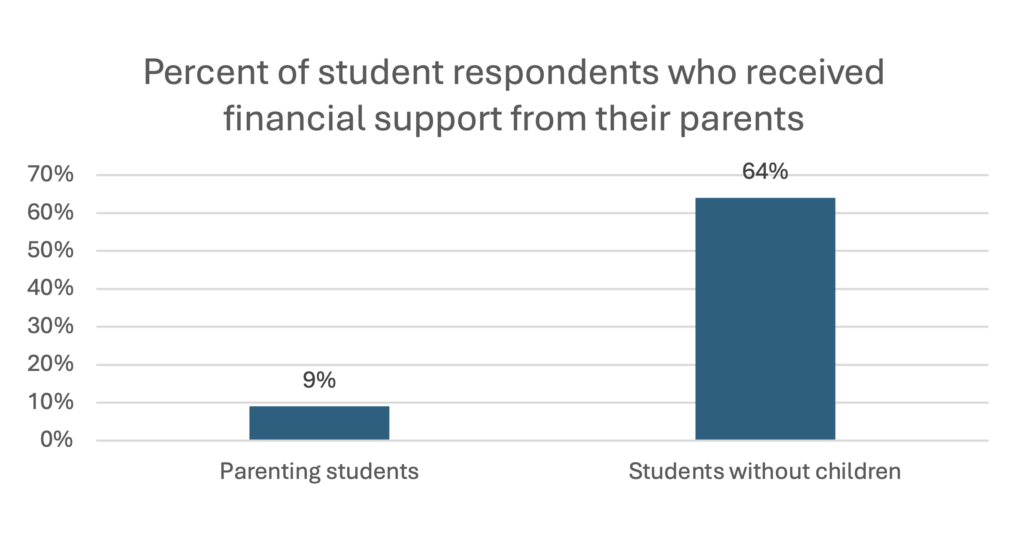

One in five students at community and four-year colleges in the United States are raising children while trying to earn their degrees—and this number may grow as access to abortion becomes more limited. Many student parents find themselves in precarious economic positions, and are often on their own to pay for college. As we found in a new study of students at two public four-year universities, fewer than 1 in 10 (9%) student parents got financial help from their own parents to pay for college tuition or living expenses. By contrast, nearly two-thirds (64%) of childless students received financial help from their parents.

The higher education landscape continues to evolve, serving a more diverse student body. The average college student today is no longer the carefree, wealthy 18–22-year-old highlighted in American movies. Although higher education—and the economic benefits that come with it—are available to more people, there is a fundamental mismatch between how colleges were designed and the realities of many of today’s students. Higher education was designed for students to depend on their families, with students’ parents largely footing the bill.

But, as our new study in The Journal of Higher Education finds, that is often not the reality students with children face. Although student parents tend to be older than students without children, differences in age or background (race, parents’ education, region, gender, grew up in US) don’t explain all of the gap in help from their parents. When examining students of the same age and background, we found that the odds that a student parent received help from their parents to pay for college was one-third of that of a student without children.

This disparity puts barriers to graduation in front of the 3.1 million undergraduate student parents pursuing higher education to better the lives of themselves and their children. Instead of getting help from their parents, student parents must draw on a unique and complex set of resources to pay for tuition and living expenses while navigating a college system that was not designed for them.

Examining how Student Parents Pay for College

To examine how student parents pay for college, we analyzed unique survey data collected in 2017 from 2,830 students at two regional public universities. Of those who completed the survey, 338, or 12 percent, identified as parents—a rate comparable to the national rate of student parents at public four-year colleges and universities.

More than half of the student parents that we surveyed used student loans, Pell grants, or money earned from a job to pay for college—the same resources that many of their fellow students without children rely on. But, parents and nonparents rely on these resources to different degrees. And, student parents can’t count on their families to pay for higher education in the same way that childless students do—and the way the system was designed.

Why don’t students with children get support from their parents when paying for college? After all, they have additional expenses and responsibilities compared to students without children.

One reason is that students who have children are more likely to be considered “adults,” so their families may believe that they should be more financially independent. Or, their families may want to support them through college – but may not be able to do so. Student parents tend to come from families with fewer resources, so their parents may not have extra cash on hand to help them with rent or tuition.

So how do student parents pay for college, if they aren’t getting help from their parents?

Instead of Relying on Support from their Parents, Student Parents Rely on Support from Romantic Partners and the Government

Many student parents rely on support from romantic partners, including spouses: in our survey we found that 43 percent of student parents used a partner’s money to pay for educational and living expenses, compared with less than 10 percent of students without children.

The support that student parents received from their partners didn’t necessarily make up for not getting financial support from their parents, though. The proportion of student parents who received support from either their parents or partnerswas less than the percent of students without children who received support from their parents.

Student parents also turn to Pell Grants—a federal grant program for students with low incomes or who have parents with low incomes. Two-thirds (66%) of student parents in our study used Pell Grants to pay for college. Once background characteristics are taken into account, the odds that a student parent used Pell Grants was more than three times that of students without children.

Policy Pitfalls for Student Parents

As student parents pursue higher education, they navigate a funding environment at odds with the realities of their lives.

Pell grants do not typically cover the full cost of tuition, much less living expenses. Perhaps because of the relatively low value of Pell grants, and because students with children could not rely on their parents’ financial support, we found student parents took out higher amounts of student loans. They were also more likely to work while in college.

Juggling a job, child care, and college while also navigating a complex financial situation makes it harder to complete a degree. Indeed, research shows that although student parents have GPAs as high as students without children, they are more likely to leave college without a degree.

But completing a college degree can really pay off for student parents—and their children. One study focused on single mothers found that those who completed a four-year degree were one-third as likely as those who had a high school degree to live below the poverty line, and earned an additional $625,000 across their lifetime. Single mothers who completed a college degree were also less likely to use public assistance programs and contributed more tax revenue.

So what can we do to facilitate success for student parents?

Within the financial aid system, it is critical that financial aid officers are trained to best support students with children. Child care expenses can be factored into loan and grant packages, but many financial aid officers do not communicate this information to students. Pell grants can also be expanded to cover a larger share of tuition and living expenses.

Beyond the financial aid system, many student parents are eligible for federal anti-poverty programs aimed at families with children, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Child Care Development Fund (CCDF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and tax credits including the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC). Navigation services on campus can help student parents access this disparate patchwork of supports.

Although many student parents turn to these programs to make ends meet, they are often penalized for being in school. Many of these programs are structured in ways that prevent student parents from receiving full benefits. Work requirements in some states do not fully count going to school. And, other programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, provide lower benefits to workers who earn the least money.

Schools can also help lower costs for student parents by expanding affordable child care offerings to their students, and building affordable family housing on campus, as most colleges do not allow students with children to move into campus housing or have on-campus child care for students.

Training financial aid officers on the needs of student parents, expanding Pell funding, reforming anti-poverty programs to value the long-term investment of pursuing higher education, and building infrastructure on campus that supports parents could help support student parents to complete their degrees—increasing their long-term economic stability and self-sufficiency—which will benefit their children as well.

Acknowledgements

The study discussed in this briefing paper is published in The Journal of Higher Education. We would like to thank JR Moller and Stephanie Pruitt for their research assistance. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1947603, and a University of North Carolina at Greensboro Advancing Research Summer Award Grant and Faculty Research Grant, as administered by the Office of Sponsored Programs.

Links

Brief report: https://sites.utexas.edu/contemporaryfamilies/2025/04/02/student-parents-brief-report/

Full study: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00221546.2025.2480024/

For more information, please contact:

Renee Ryberg, Senior Research Scientist, Child Trends

rryberg@chidltrends.org

Website: https://www.childtrends.org/staff/renee-ryberg

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/renee-ryberg-8b2a1a2b/

ABOUT CCF

The Council on Contemporary Families, based at the University of Texas-Austin, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization of family researchers and practitioners that seeks to further a national understanding of how America’s families are changing and what is known about the strengths and weaknesses of different family forms and various family interventions.

The Council helps keep journalists informed of new and forthcoming research on gender and family-related issues via the CCF Network. To locate researchers or request copies of previous research briefs, please contact Stephanie Coontz, Director of Research and Public Education, at coontzs@msn.com, cell 360-556-9223.

Follow us! @CCF_Families and https://www.facebook.com/contemporaryfamilies

YouTube: @contemporaryfamilies

Read our blog CCF @ The Society Pages – https://thesocietypages.org/ccf/