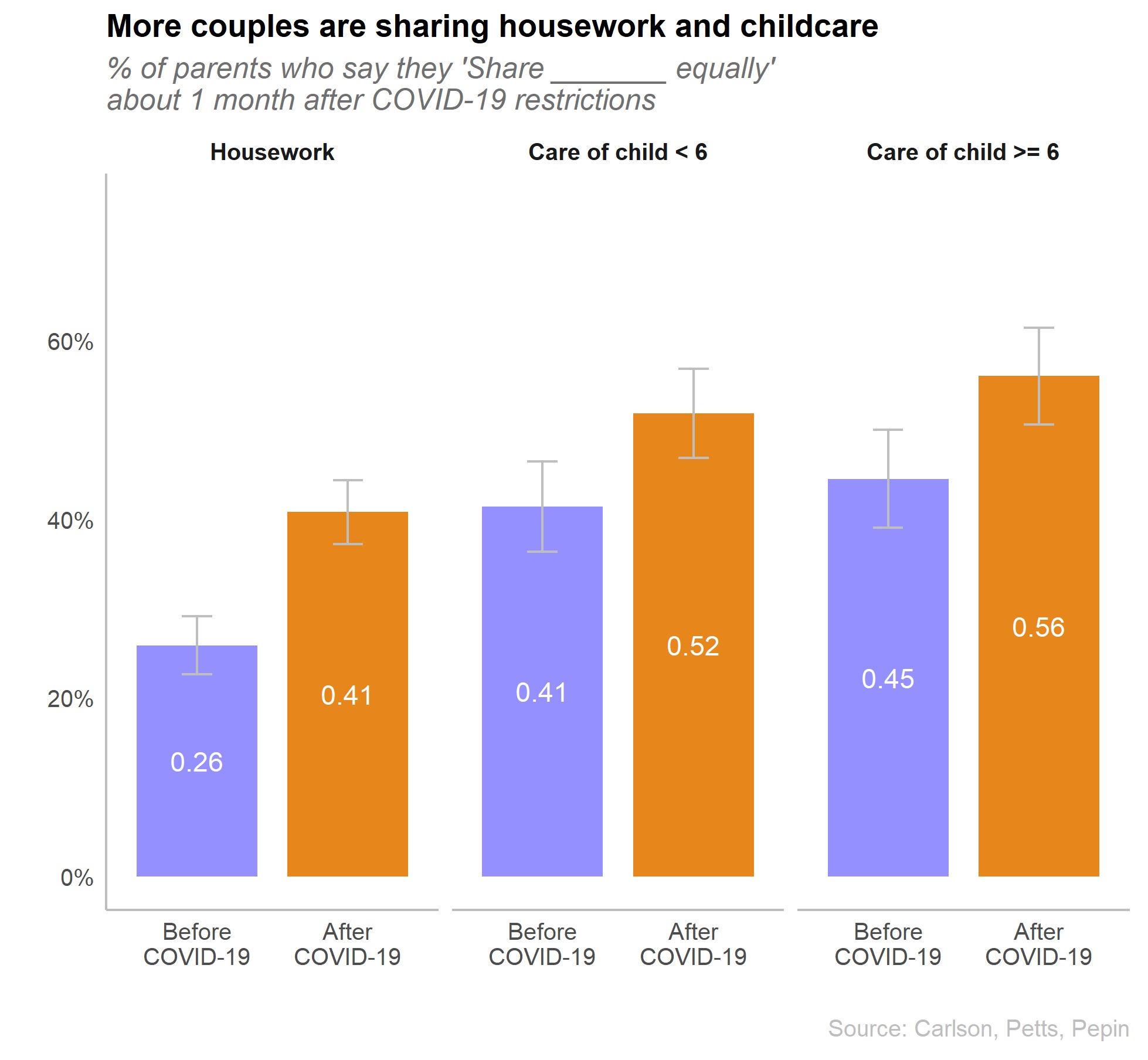

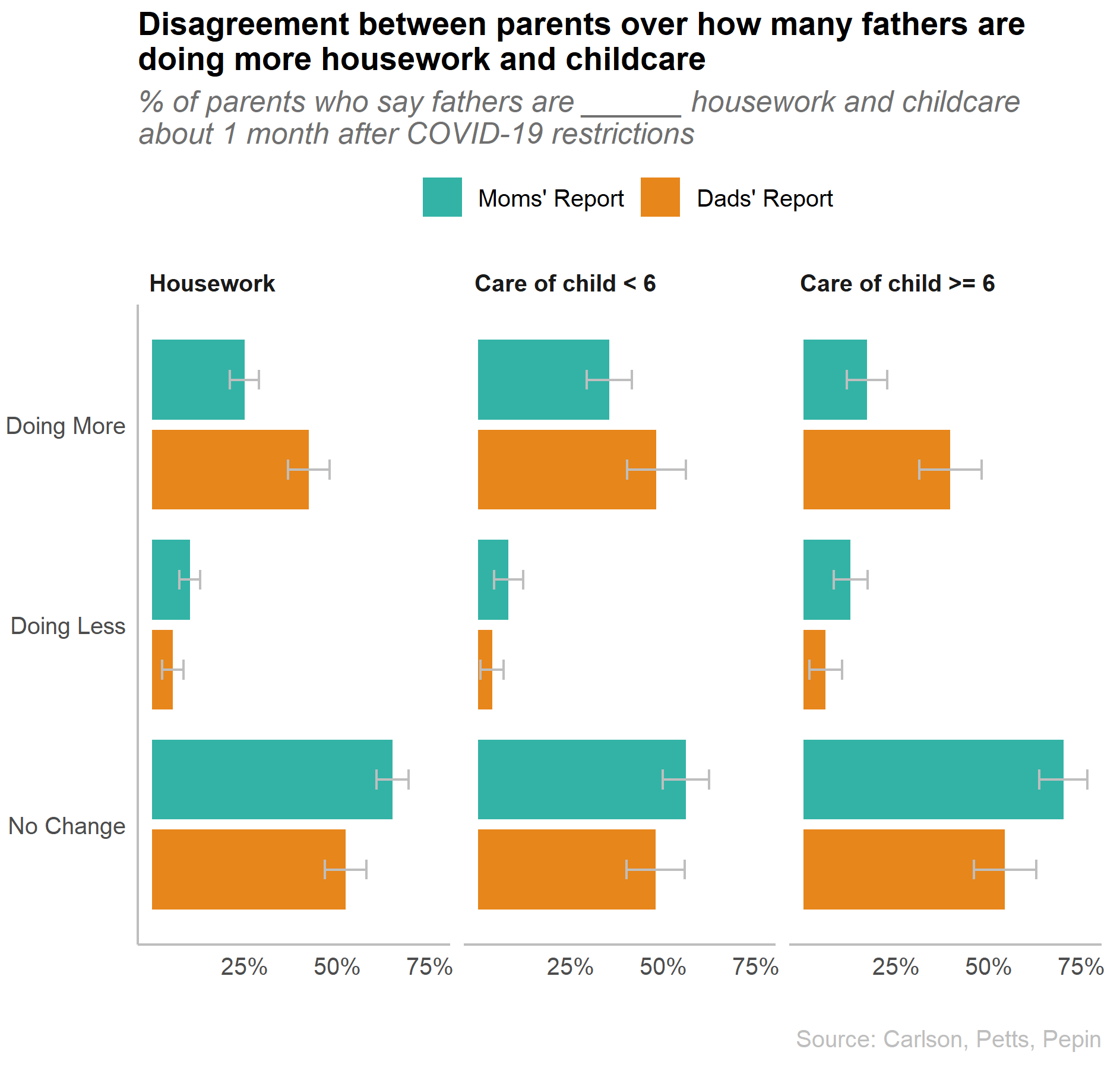

CCF experts Dan Carlson, Richard Petts, and Joanna Pepin discuss the findings of their latest brief report on gendered division of labor during the covid-19 pandemic with Deseret News’ Lois M. Collins.

Read the article, “More men are doing housework during the pandemic, research finds,” here.

UPDATE: read more coverage of CCF’s latest brief report in the Boston Globe’s, “Men are taking on (slightly) more household chores during pandemic,” as well as The Washington Post’s, “The pandemic didn’t create working moms’ struggle. But it made it impossible to ignore.”