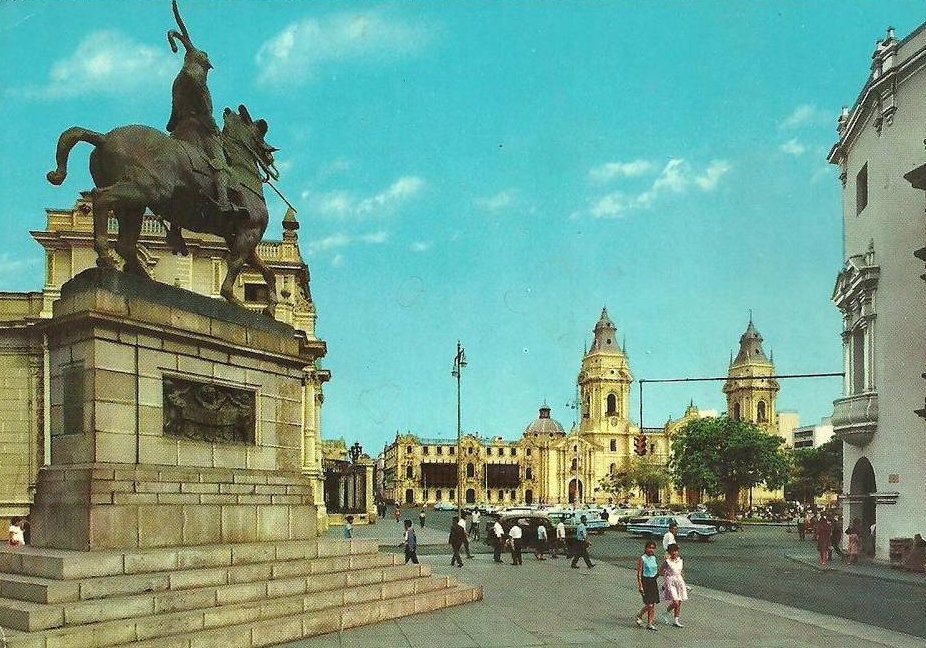

The monument of Francisco Pizarro (1470/71 – 1541) in Lima is the work of the American sculptor Charles Cary Rumsey (1879 – 1922). In 1913 Rumsey received an invitation to contribute a large equestrian statue of Pizarro to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915. His work appears to have been well-received. Other copies were cast later, and three of them are extant today: in Buffaly, NY, in Trujillo, Spain (Pizarro’s place of birth), and of course in Lima, Peru. This particular bronze statue was donated to the city of Lima by his widow Mary Harriman Rumsey (1881 – 1934) and unveiled on January 18, 1935, on the occasion of the fourth centenary of Lima’s founding by Pizarro.

Francisco Pizarro led a brutal and bloody campaign to conquer and subjugate the Inca empire. His expedition reached northern Peru in 1532, and he founded the city of Lima in 1535 which was going to become the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1541. Later in 1535 he entered the Inca capital of Cusco, thus completing his conquest of the Inca empire. Pizarro was murdered in Lima in 1541 by a fellow Spaniard as a result of political conflict among colonizers–which was a common feature of the Conquest.

While the landscape of South America is dotted with monuments to the two main South American liberators Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) and José de San Martín (c. 1778–1850), why would the city of Lima set up a monument to Francisco Pizarro? The reasons lie in the way the Peruvian Republic, which declared its independence in 1821, dealt with the colonial past.

Even though the revolutionaries and liberators of the early 19th century, like Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, were of Spanish descent, they pursued a distinct nationalist Peruvian (and South American) identity that was detached from the Spanish colonial masters, following the path the United States had taken from 1776 onward. In the 1860s, the Republican governments started to transform Lima into a modern capital which was modeled after Paris; it featured wide avenues and large stately buildings in the then-dominant neo-classical style. The imitation of the European colonial masters had become acceptable again.

After World War I, a neo-colonial style became more fashionable, the palace of the archbishop (1924) next to the cathedral perhaps being the best example. This conscious reflection on the civilizing legacy of the Spanish colonizers on the Peruvian Republic was in part in response to growing indigenist viewpoints that framed the Spaniards as brutal colonizers who had committed genocide. It also was a tribute to a rising European fascism which had a significant impact in Latin America and to which many in the elites had an affinity. It is in that context that the veneration of Pizarro became a point of identification among the Peruvian elites. In 1928, a chapel celebrating Pizarro’s achievements was dedicated in the historic Lima Cathedral, including a memorable mosaic showing Pizarro entering a primitive and depraved Peruvian landscape.

This was followed by the erection of said monument to Pizarro just a few steps away in 1935. In his opening speech at the unveiling of the Pizarro monument in 1935, Lima mayor Luis Gallo Porras (1894 – 1972) called the statue a “figura preclara del héroe y del civilizador” (illustrious statue of the hero and civilizer).

Initially, the monument was located in front of the Cathedral on the Plaza de Armas (Plaza Mayor), the most prominent and symbolic space in the entire city of Lima. From the very beginning, the placement of the monument caused conflict. Due to complaints from the Archdiocese of Lima, the statue was moved to a small square off the Northwest corner of the Plaza de Armas, between the Presidential Palace and Lima’s Palacio Municipal, in 1952. The small square then was called Plaza Pizarro.

Conservatives saw it appropriate to commemorate the founder of the city and to celebrate the colonial roots of contemporary Peru. They likened the Spanish conquest of Peru to the Roman conquest of Spain and argued that Peru in its essence was Spanish. Progressives viewed the monument as a symbol of colonialism and oppression and argued that Lima should not honor the destroyer of the Inca culture and oppressor and murderer of Peru’s indigenous people. They viewed Peru as a nation rooted in indigenous culture which survived centuries of efforts to eradicate it.

As a clear majority of the Peruvian population identifies with indigenous cultures, the political mood was changing in this direction in the last quarter of the 20th century. In 2003, Lima Mayor Luis Castañeda Lossio ordered the removal of the statue. The plaza was remodeled and renamed “Plaza Perú”. The statue was eventually placed into a remote corner of the Parque de la Muralla (park of the wall), a park that was developed at the time as part of a project to protect remnants of the historic city wall which were discovered during a construction project a few years earlier. The statue also has been deprived of the large and commanding base which it enjoyed in its previous two locations–the equestrian monument has been demoted to a pedestrian level. While the statue still is publicly displayed, it is clear that Pizarro has been exiled to an insignificant spot outside the boundaries of colonial Lima.

Pizarro is founding father to some and war criminal to others. His monument is a lightening rod for ongoing political conflicts between the conservative elites mostly of Spanish descent and progressive forces who identify with and support the cause of Peru’s indigenous majority. It is symbolic for the negotiations to create a unified national identity and for the ongoing effort to define a hybrid culture that in some form existed ever since Pizarro arrived. As the conflict surrounding the Pizarro monument illustrates, even two centuries after Peruvian liberation, the legacy of colonial rule is omnipresent in Peruvian culture and political discourse.