Visuals can be valuable tools for persuasion in briefs.

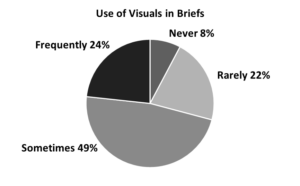

Legal writers should use visuals as persuasive tools in their documents, and it’s already happening: In my survey of 133 lawyers, 70% said they frequently or sometimes use visuals in briefs. The survey targeted writers of persuasive documents at an initial-dispute stage: trials, administrative hearings, arbitrations, and others.

This article displays a simple pie chart showing the answers to survey question 2: “In writing briefs or other persuasive documents, do you ever use visuals: graphics, images, charts, tables, illustrations, and so on?

In part one of this series, I’ll discuss the recommendations in favor of visuals from experts and practicing lawyers.

As the survey results show, many legal writers are already using visuals in briefs. That only makes sense because those who research and write about using visuals have been recommending the practice for several years. Here are two experienced practitioners in 2019:

- “Using images in briefs can be an effective tool for both catching and keeping the attention of a ‘wired’ judge or clerk and for increasing the persuasive force of your legal argument.”[1]

Here’s a 25-year in-house lawyer, writing in 2013:

- “Well-crafted images—charts, diagrams, photographs—can make your briefs more interesting and persuasive ….”[2]

No, the written word isn’t dead, said two legal-writing professors in 2015, but “[a]s legal writing moves toward a more digital medium, it is time for lawyers to incorporate visual persuasion into their documents.… [Visuals users] are advancing legal writing in a positive direction.”[3]

My survey produced some supporting recommendations as well. In responding, writers could choose from a list of the potential benefits of visuals, and here are the top three responses:

- Sometimes visuals can convey concepts that text cannot;

- Sometimes using visuals is easier than describing something in the text; and

- Visuals add persuasive force to the document.

Survey respondents could also add comments, and there were several strong endorsements:

- “Using graphics, charts, etc. can be very helpful to a brief and the judge’s understanding of the issues.”

- “I use tables and charts as often as it makes sense. When I was clerking, I found graphics in briefs to be generally helpful. One table compared specific allegations in the complaint with what the plaintiff had ultimately presented on that point after discovery. The discrepancies were already glaring, but the table really nailed it.”

- “I use tables and charts when they help organize the information: with multiple parties and I’m trying to display the differing facts about each one, in discovery disputes—breaking down the disputed-information categories, for financial information, and in timelines.”

- “In a case with multiple claims and multiple defendants, I created a table in which each row was a specific claim against a specific defendant. In the columns, I briefly explained why that claim failed and cited a key case.”

To these endorsements we can add the obvious point that lawyers have used visuals for live trials and hearings for many years. It’s taken for granted that photos, maps, charts, and other visuals have a strong persuasive impact on judges and juries. So it’s not surprising that the same is true for briefs.

Yet 30% of my survey respondents said that they rarely or never use graphics in briefs. Why not? I’ll address that in the next part of this series.

_____

[1] Emily Hamm Huseth & Michael F. Rafferty, A Picture Can Save a Thousand Words: The Case for Using Images in Appellate Briefs, For the Defense 22, 23 (Feb. 2019).

[2] Adam L. Rosman, Visualizing the Law: Using Charts, Diagrams, and Other Images to Improve Legal Briefs, 63 J. Leg. Educ. 70, 70 (Aug. 2013).

[3] Steve Johansen & Ruth Anne Robbins, Art-iculating the Analysis: Systemizing the Decision to Use Visuals as Legal Reasoning, 20 J. of the Leg. Writing Inst. 57, 59, 60 (2015).