BY KELLY McDONOUGH

One of the main attractions among the rare books and manuscripts at the Benson Latin American Collection is a group of late-sixteenth-century manuscripts and maps known as the Relaciones Geográficas (or RGs for short). As described in the Benson’s web portal to the RGs, these manuscripts are responses to a fifty-question survey sent by the Spanish Crown in 1577. The survey requested information about Spanish-held territories in the Americas. Many of the questions focused on the population, cultural practices, physical terrain, vegetation, and other material resources. The Benson holds 43 of the 167 extant responses and accompanying maps (the rest are in archives in Spain). Scholars travel from around the world to Austin every year to work with the RG maps. Recently, however, one of the RG maps did some traveling of its own. On October 5, 2015, as part of a tribute to Mexican indigenous studies scholar Dorothy Tanck de Estrada at the Teatro de la Ciudad in Puebla, Mexico, I had the honor of presenting a stunning reproduction of the 1581 RG map of Cholula to eighteen traditional indigenous authorities (fiscales and mayordomos) of San Pedro and San Andrés Cholula. The theater was standing-room-only as more than 200 attendees witnessed this return of historical memory to the people of Cholula.

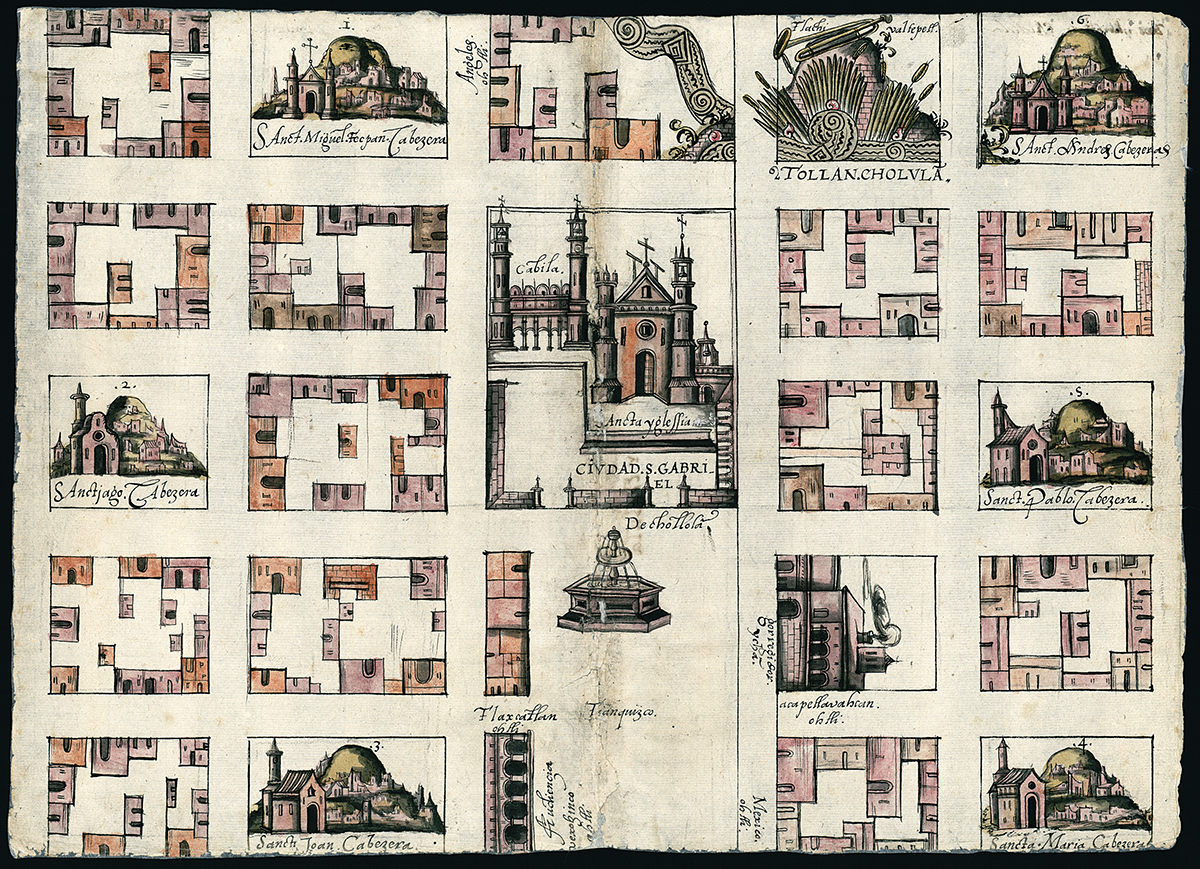

Question number ten of the survey requests a pintura or a painting—meaning a map—of the town(s) in question. The map was to include “the location and center of said towns, if the area is highlands or lowlands, or plains; with a sketch of the design, painted, of the streets and plazas and other places such as monasteries, however one might easily draw this up on paper, and that it identifies which part of the town faces north.” (“El sitio y asiento donde los dichos pueblos estuvieren, si es en alto o en bajo, o llano; con la traza y designio, en pintura, de las calles y plazas y otros lugares señalados de monasterios, comoquiera que se pueda rasguñar fácilmente en un papel, en que se declare qué parte del pueblo mira al mediodía o al norte.”)

The resulting maps were for the most part drawn and/or painted by anonymous indigenous men, providing rare insight into indigenous perspectives of cultures in contact during the first century of colonization in Mexico (for more information, and to see several of the digitized RG maps, visit Relaciones Geográficas).

One of the things I like most about my research is that I don’t just study indigenous sources from Mexico, but I try to ensure that indigenous peoples have access to these sources as well. Since coming to UT Austin in 2012, it has been a goal of mine to return a reproduction of each of the 43 RG maps to their communities of origin. Knowing that I would be in Cholula for a conference this fall, I asked Julianne Gilland, director of the Benson Latin American Collection, if we might begin with the map of Cholula. She enthusiastically agreed and swiftly oversaw the beautiful reproduction and framing of the map. Gilland also wrote a generous letter in Spanish on behalf of the Benson. Her letter, also signed by the men and women who received the map with great reverence and emotion, is being translated into English and Nahuatl as well, and will soon hang framed next to the map in Cholula.

Seven of the major barrios of Cholula are depicted on the 1581 map, each with its own Catholic Church and mountain, the latter representing the pre-Hispanic indigenous place of worship. It was common practice to build the churches directly on top of such places of worship. Whether the indigenous map-maker/painter meant to suggest that the churches were simply built at these already-sacred sites, or perhaps that the Catholic religion had not eliminated earlier forms of worship but instead joined them, we cannot know.

The Convento de San Gabriel presides in the center of the map, illustrating Spanish dominance in the region. In the upper right-hand corner, however, we see the Nahuatl-language place-name of Tollan Cholula in bold capital letters. Tollan, “among the reeds,” often signified a mytho-historical place of origin or an urban center. Cholula refers to acholloyan, “place where the water flows.” Above the place-name we see a depiction of a mountain with grasses and reeds, the Tlachihualtepetl (literally “man-made mountain”), the largest pyramid in the Americas. The mountain spills into the quadrant to its immediate left, and is connected to a snaking shape used in indigenous painting to represent water. This association between water and the pyramid evokes the Nahuatl term for a socio-political unit—altepetl—literally, water-mountain (atl-tepetl). With this in mind, even though it is not physically represented at the center of the map of Cholula, the great pyramid is the most important image on this map in that it signals this socio-political unity, or the peoplehood of Cholutecas.

This reminder of the unity and interdependence of the major barrios comes at an important time in Cholula’s history. State and local government officials in Puebla have made steady inroads in the destruction of the platform of the pyramid of Cholula to make way for tourist attractions and commercial development. Traditional authorities and concerned citizens of Cholula have protested these activities vehemently over the past year, both in the streets and in the courts.

Two Cholultecas, father and son Paul Xicale Coyópol and Adán Xicale, were imprisoned for over a year for their participation in protests aimed at protecting the sacred site from commercial development.* Whereas in earlier 2015 the courts had temporarily halted construction, as of May 2016 many of the flower fields that covered the pyramid’s platform have already been bulldozed and covered with concrete pavers. Planters with trees and other plants have been installed, although what ought to be green is either yellowing or already dead.

What does the gift of a reproduction of a map have to do with the crisis at this archeological site? It is the traditional indigenous authorities of Cholula who have spearheaded the movement to protect the pyramid and its environs from commercial development. At times, I am told, they feel as if they are unable to stop their culture from slipping away, or in this case being covered in concrete to make way for a coffeeshop. But the return of a forgotten map some 435 years after their anonymous ancestor sketched out the town and the people has given the fiscales a renewed sense of hope that their histories and ways of life can survive, even flourish.

Kelly McDonough is assistant professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese. She is author of The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico (2014), a book that challenges the commonly held assumption that indigenous intellectual activities in Latin America ceased or decreased dramatically with the advent of European conquest and colonization.

Note

*Read more about the Xicale cases at La Jornada. Watch “Luz bajo la tierra: la destrucción de Cholula,” a 20-minute documentary on the destruction of the Cholula archaeological site.