BY ADRIAN JOHNSON

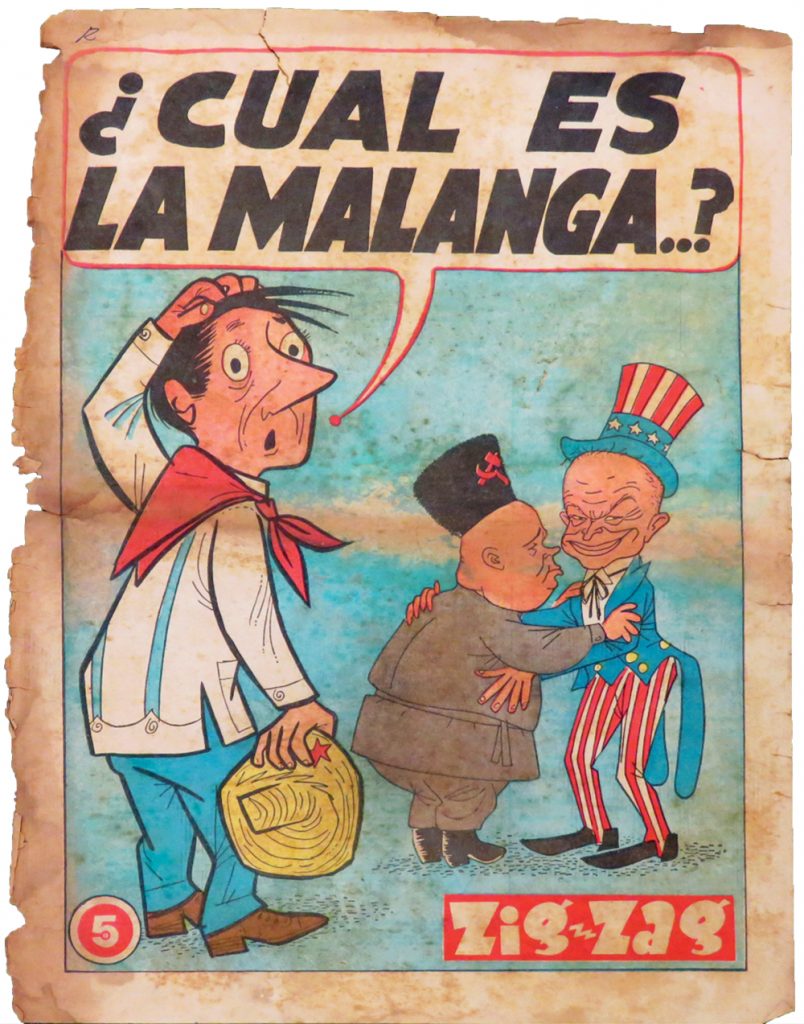

COMIC BOOKS, originally created as entertainment for children, were long relegated to dime-store magazine racks, children’s bookshelves, and the cheap bin at used bookstores. While sales of comics today are struggling, in recent years they have come to occupy a more important place in our culture than most readers in the last century could have ever dreamed. More comics today are written for adults than are written for children. Comic book superheroes are the hottest commodity in Hollywood. And scholarly focus on popular culture production like comics continues to expand.

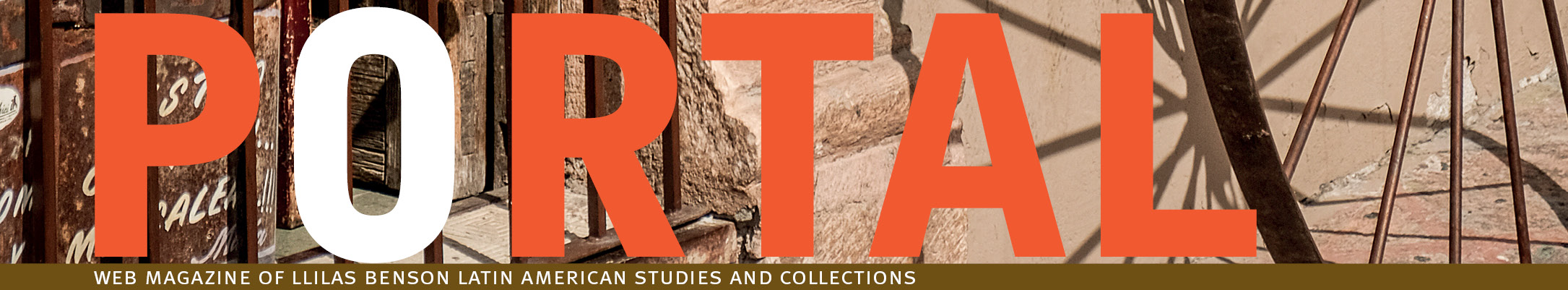

The Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection has collected Latin American and US Latinx comic books for decades. But a recent acquisition, the Caridad Blanco Collection of Cuban Comic Books / Historietas Cubanas, containing over 750 comic books and newspaper cartoon inserts, documents the history of graphic art and humor in Cuba, focusing especially on the decades following Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution.

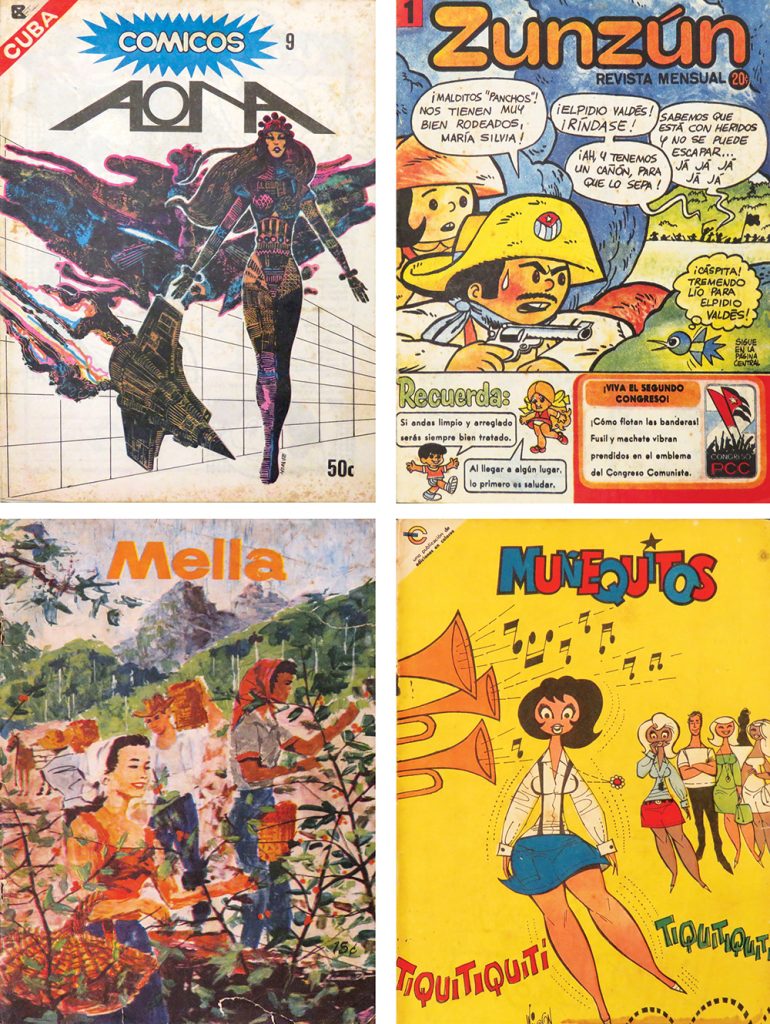

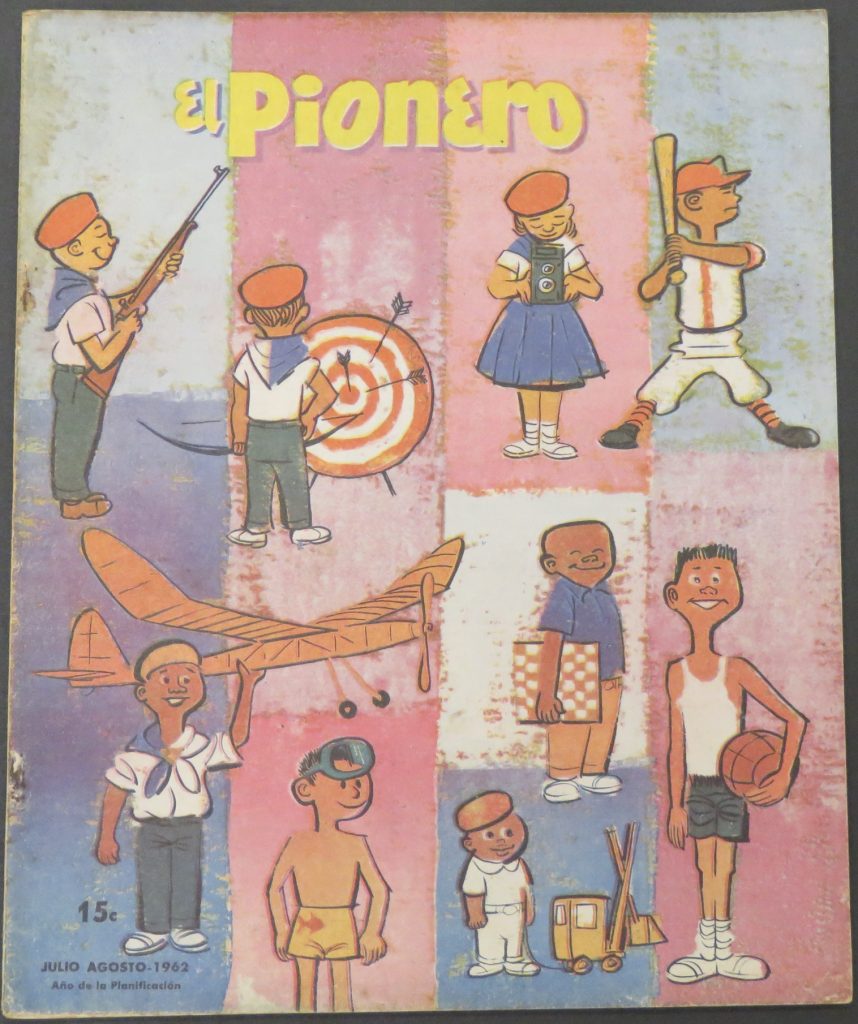

Graphic humor developed in Cuba, as in much of the West, with newspaper strips and satirical political cartoons, starting in the late nineteenth century. A strong culture of graphic art also developed in the form of trading cards, beginning with tobacco cards, and expanding in the twentieth century to collectible cards included with different food products. This tradition continued through the revolution and still remained popular for Cuban children through the end of the twentieth century. Comic books began appearing in Cuba in the early twentieth century, but were primarily Spanish-language translations of Disney and superhero comics popular in the United States at the time. With the triumph of Fidel Castro’s revolution in 1959, comic books abruptly found a new purpose and strong official support.

As the new government developed revolutionary ideals, graphic art, along with other popular art forms, was quickly put to the service of building a revolutionary nationalist consciousness. This coincided with a movement throughout Latin America focused on distinguishing national cultures and identities from those of the United States. In Cuba, US comics were quickly replaced by Cuban comics, written and drawn by Cuban artists, with uniquely Cuban themes.

Revolutionary Storylines

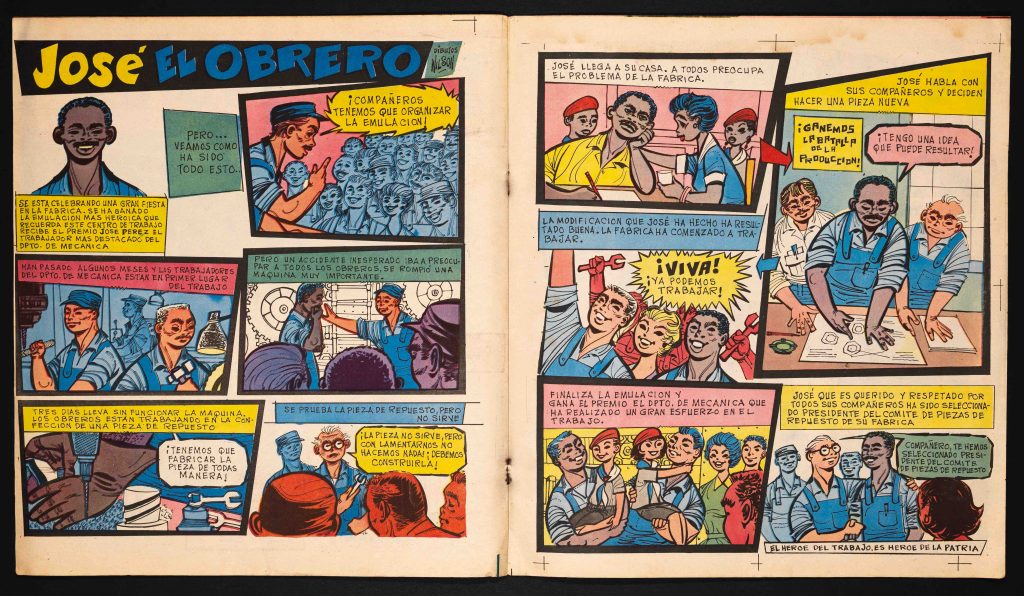

Stories took a swift revolutionary stance, urging readers to work to become the new socialist man, an identity characterized by devotion to work, individual contribution, and involvement in collective efforts. Comics told stories of the heroes of the revolution and the Cuban Independence movement, exemplified by the most popular comic book character in Cuba, Elpidio Valdés, a colonel with the peasant Mambi army fighting for liberation from Spain in the 1890s. Alongside these larger-than-life hero characters, stories focused on ordinary Cuban citizens, each doing their part to improve the quality of life for themselves and their neighbors. Protagonists are humble, don’t lie to their family or friends, they take care of themselves physically and emotionally, and always contribute to community projects. When characters make decisions counter to the revolutionary ideal, everyone comes together to get them back on track. Comics without overtly political messages at the least featured public service announcements with similar messages sprinkled among the stories.

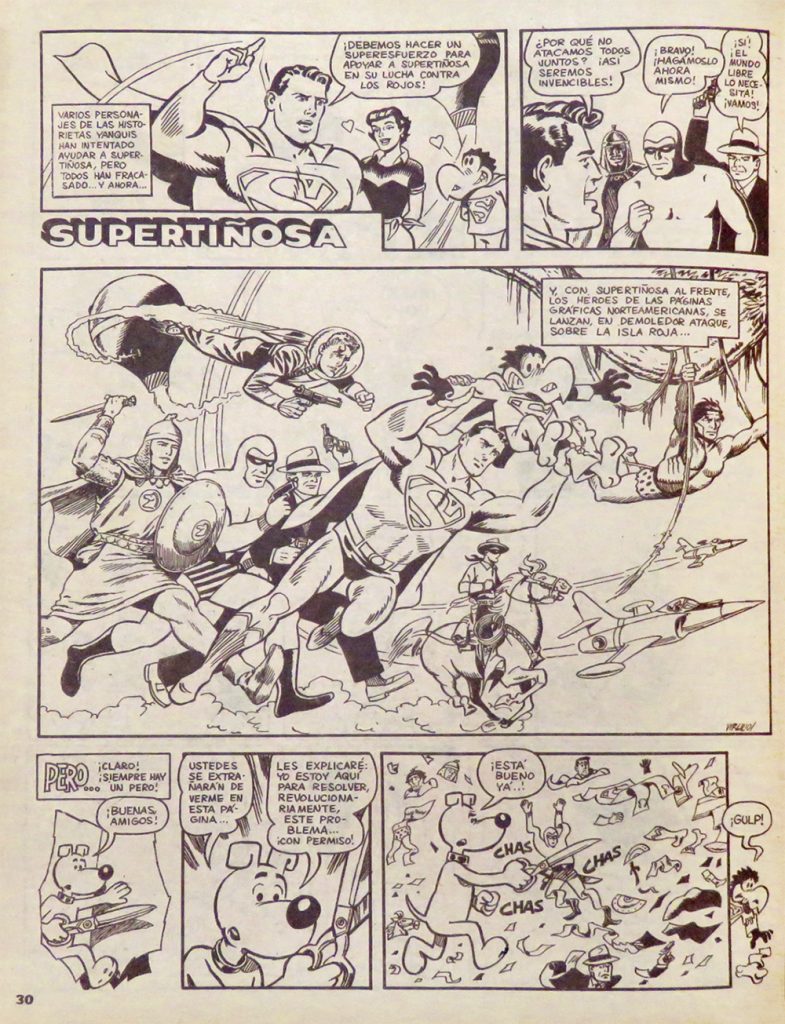

A common theme of Cuban comics is anti-imperialism. Authors did not shy away from portraying the United States as a money-addicted, racist society obsessed with overthrowing communism. Supertiñosa, for example, is a US-style superhero who works with Superman, Dick Tracy, the Lone Ranger, Captain America, and others to overthrow los rojos (the reds) in Cuba. Other comics focus on historical imperialism, such as the character Yarí, an indigenous Taíno constantly struggling (and triumphing) against the Spanish conquistadores. Portrayal of Afro-Cubans stands in stark contrast to common US portrayals (and absences) of African Americans during the 1960s and 1970s.

Graphic Art and Artists under the Embargo

While many of the Cuban comics feature artistic styles similar to comics universally, multiple factors led to distinctive and unique graphic art. Cuba’s revolutionary government strongly and actively supported the arts. The nation was small and highly literate, with granular, if sometimes forced, participation in building a revolutionary society. Opposition to the United States and the embargo remained high among those artists who stayed in Cuba, especially in the first decade. Finally, artists had to be creative and inventive simply due to lack of materials like paint and paper, resulting from the embargo. All of these factors set Cuban graphic art apart from contemporary trends elsewhere the world. This collection encapsulates and documents these uniquely Cuban trends from the 1960s onward.

The collection’s namesake, Caridad Blanco de la Cruz, is a curator at the Centro de Desarrollo de las Artes Visuales (Center for the Development of the Visual Arts) in Havana. Comic books and graphic art and humor are a lifelong passion. She is a graphic art scholar, has published articles and books on the topic, and created numerous exhibitions spotlighting Cuban comic book artists in Cuba and in Europe. Her most recent book, published in April 2019, is Los flujos de la imagen: Una década de animación independiente en Cuba (2003–2013). Blanco has collected comic books throughout her life, resulting in a collection carefully curated to reflect the most important themes, artists, characters, publishers, and newspaper inserts of the last sixty years. One of her lifelong goals has been to elevate graphic humor in Cuba to the status of a fine art, worthy of serious consideration in the art world and the scholarly universe. This collection will be a treasure trove for scholars of literature, art, public relations, history, political science, African diaspora studies, Latin American studies, and much more.

Adrian Johnson is librarian for Caribbean Studies and head of user services at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection.

View the Caridad Blanco Collection of Cuban Comic Books via Texas Archival Resources Online.

Related Collections

Cuban Comic Books and Graphic Fiction Collection (1952–2017)

Cuban comic books, graphic novels, zines, and other graphic fiction.

https://txarchives.org/utlac/finding_aids/00504.xml

Puerto Rican Popular Culture Print Materials Collection (1974–2015)

Comic books, zines, cartoneras, and other popular culture and graphic

fiction materials from Puerto Rico.

https://txarchives.org/utlac/finding_aids/00505.xml

Libros Latinos Latino Comics Collection (1992–2005)

Comic books, zines, graphic novels, posters, and ephemera acquired from San Francisco–based bookseller Libros Latinos.