BY EDWARD SHORE

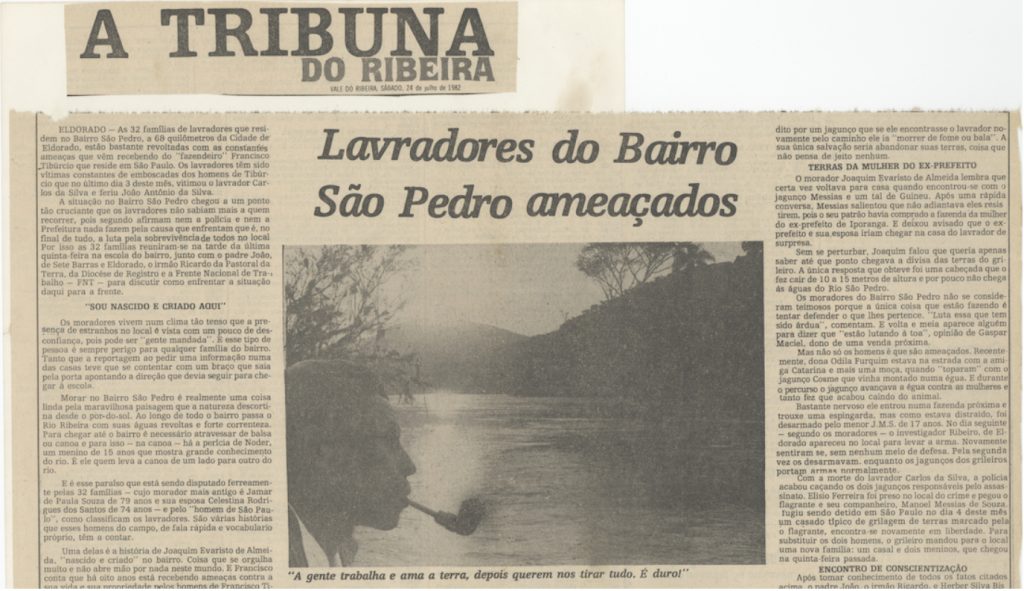

CARLITOS DA SILVA was an activist and community leader from São Pedro, one of 88 settlements founded by descendants of escaped slaves known in Portuguese as quilombos, located in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil’s Ribeira Valley (Vale da Ribeira). During the early 1980s, amid an onslaught of government projects to develop the Ribeira Valley through hydroelectric dams, mining, and commercial agriculture, da Silva defended his community against Francisco Tibúrcio, a rancher from São Paulo. In 1976, Tibúrcio falsified a deed to usurp lands belonging to the residents of São Pedro, a practice known in Brazil as grilagem. When da Silva and his neighbors refused to leave, Tibúrcio dispatched thugs to intimidate residents, burning down homes and setting loose cattle to trample the community’s subsistence garden plots (roças). Several families relocated to the sprawling shantytowns of Itapeuna and Nova Esperança, joining thousands of refugees from rural violence throughout the Ribeira Valley. Yet many others, including Carlitos da Silva, fought back.

Supported by Liberationist sectors of the Brazilian Catholic Church, da Silva and his neighbors pursued legal action against Tibúrcio and his associates. In 1978, they formed a neighborhood association, claiming collective ownership to their lands based on usucapião, equivalent to the English common-law term “adverse possession,” meaning “acquired by use.” Their militancy coincided with a wave of activism throughout the Brazilian countryside, as Indigenous peoples, landless workers, and descendants of slaves pressed for agrarian reform and reparations. Large landowners, flanked by rural politicians and the police, responded with repression. On the morning of July 2, 1982, assassins gunned down Carlitos da Silva in the doorway of his home, in front of his mother, wife, and young children. Francisco Tibúrico had sought to crush the São Pedro neighborhood association by silencing one of its leaders. Yet the assassination of Carlitos da Silva became a rallying cry, emboldening the descendants of quilombos throughout the Ribeira Valley to fight for land rights and social justice.

“We were threatened. Some of us left [São Pedro] and others fled the region altogether,” Aurico Dias of Quilombo São Pedro told me in a 2015 oral history. “But thanks to our faith in God, we were able to rise up again, quickly, and discovered the courage to take back what was ours.”

Preserving the Voices of the Silenced

I learned about Carlitos da Silva’s story while conducting archival research at the Equipe de Articulação e Assessoria às Comunidades Negras (EAACONE, Articulation and Advisory Team to Rural Black Communities of the Ribeira Valley, formerly MOAB, the Movement of Peoples Threatened by Dams), an Eldorado-based civil society organization that defends the territorial rights of quilombos residing in the Atlantic Forest of São Paulo state and Paraná. During my first trip to EAACONE in 2015, I found a dossier documenting the history of political activism for communal land rights in São Pedro, a village established during the 1830s by a fugitive slave, Bernardo Furquim, and his companions, Coadi and Rosa Machado, near the banks of the Ribeira de Iguape River.

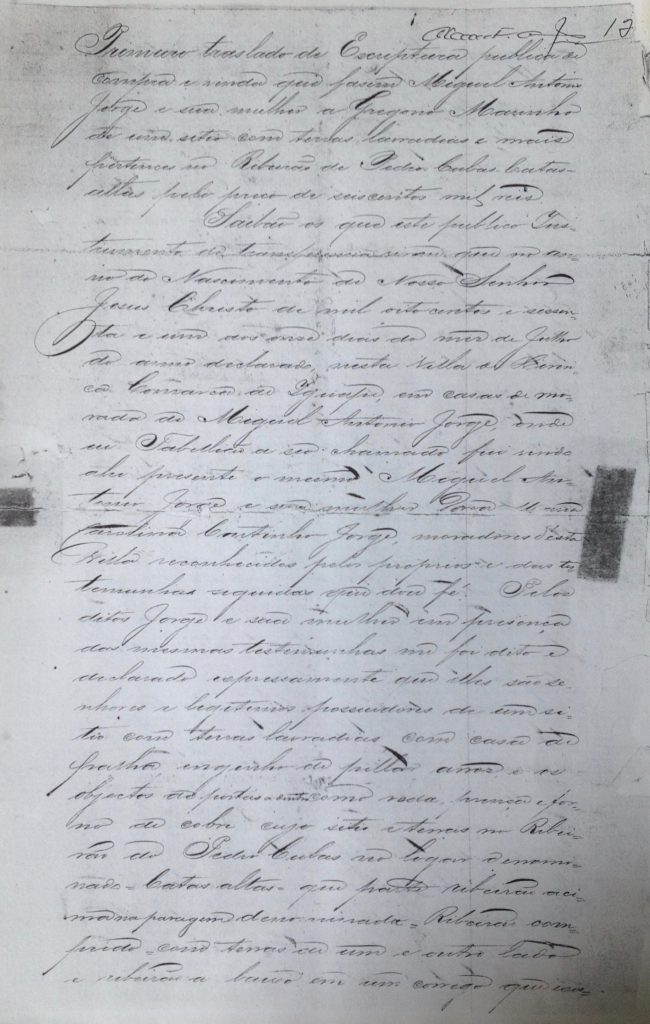

The dossier was the tip of the iceberg. For more than thirty years, MOAB/EAACONE’s staff has compiled historical documentation—property deeds, baptismal records, court documents, photographs, and oral histories—to strengthen the legal claims of quilombos to their ancestral lands. In 1994, the quilombo community of Ivaporunduva brandished land titles belonging to Gregório Marinho, a fugitive slave, as historical evidence of their long-term territorial dominion when its residents sued the Brazilian government for failure to apply Article 68, a constitutional provision that accords land rights to the descendants of maroon communities. The lawsuit, the first of its kind in Brazil, paved the way for thousands of quilombo communities to enlist history and genealogical memory to demand collective land rights.

Archives at Risk

These archival materials documenting the history of the African Diaspora in Brazil are at risk. Government officials have enacted deep cuts to public education, museums, and state archives in the aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis. Although the National Archives in Rio de Janeiro and the Public State Archive of São Paulo have digitized vulnerable materials, many archives and museums throughout Brazil have fallen into disrepair. The electrical fire that tore through Rio’s National Museum in 2018 destroyed priceless artifacts and historical patrimony pertaining to indigenous peoples and Afro-Brazilians.

Collections documenting underrepresented populations in Brazil, especially quilombos, are politically vulnerable, as well. In 1890, two years after abolition, Finance Minister Rui Barbosa ordered the treasury to burn all records related to slavery, in part to stave off the demands for the indemnification of slave owners, but also to suppress the historical claims to land rights and reparations that quilombola activists assert today.

In 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro declared war on rural activists, pledging to amend the Brazil’s terrorism laws to prosecute members of the Movimento Sem Terra (MST, or Landless Workers Movement) and vowing never to cede “another centimeter” of land to quilombos and Indigenous communities. Amnesty International has reported sabotage, arson, and hacking of human rights activists and progressive civil society organizations throughout Brazil. In light of the dire political situation confronting traditional peoples in Brazil over the past several years, and given EAACONE’s gracious support for my research, I wanted to give back. Then fate intervened.

Forging a Transcontinental Partnership

In spring 2015, LLILAS Benson announced a “call for partners” to support post-custodial initiatives1 in Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil, with particular emphasis on archival collections documenting human rights, race, ethnicity and social exclusion. I excitedly shared the news with my friends at EAACONE and the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA, or Socio-Environmental Institute), a São Paulo-based NGO that defends the social and environmental rights of traditional peoples in Brazil and a longtime ally of MOAB/EAACONE.

Although my colleagues in Brazil were intrigued by the project, they voiced serious concerns related to privacy, access, and power. EAACONE is hardly a traditional archive. In fact, the collection serves primarily to furnish historical evidence to support quilombos’ legal battles for land and resources. While EAACONE grants access to their archive to vetted researchers, the organization was understandably reluctant to publish any sensitive materials that might jeopardize ongoing cases. Furthermore, their members underscored the necessity of maintaining intellectual and physical control of their collections in their original context. They pointed to the sordid legacy of imperialist collecting practices, whereby researchers from the Global North extracted documentary heritage from communities in the Global South and re-concentrated them in museums and archives in Europe and the United States.

In a similar vein, members of quilombos have long lamented how scholars have conducted academic research in their communities, only to withhold their findings or publish them in English. EAACONE and ISA were eager to participate in the post-custodial project, but only if it promoted collaborative partnership to advance the territorial and socio-environmental rights of quilombo communities.

We took their concerns to heart. Over the next four years, I worked with Rachel E. Winston, Black Diaspora Archivist at LLILAS Benson, to build trust and foster partnership between EAACONE, ISA, and LLILAS Benson. “There is something very powerful in helping to facilitate a community’s efforts to document themselves and their experiences. To that end, one of the things that has to be examined very carefully is the equity of the partnership,” Winston later reflected. “This is something that, at its core, has to serve a meaningful purpose for our partners and the larger institutional goal of providing online access to vulnerable, underrepresented, important documents.”

In November 2015, LLILAS Benson invited Frederico Silva, an anthropologist at the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) in Eldorado, to participate in a workshop in Austin, Texas, alongside representatives from archival collections in Mexico, Colombia, and Central America. Two years later, in spring 2017, I invited Silva and Vanessa de França, a teacher and community activist from Quilombo São Pedro, to Austin to participate in a roundtable discussion about threats to quilombola agriculture and food security at the Lozano Long Conference. (Read the related article, “Brazilian Roças: A Legacy in Peril.”) Last summer, Rachel Winston and I traveled to Eldorado to deliver our pitch to EAACONE and ISA personally. We assured their full autonomy in selecting materials for digitization and publication, guaranteeing that sensitive documentation would remain inaccessible to the public. In August 2018, members of EAACONE and ISA voted to accept our proposal, joining the Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN, or Process of Black Communities, Colombia) and the Fondo Real de Cholula (Royal Archive of Cholula, Mexico) as members of LLILAS Benson’s second post-custodial cohort2 in Latin America.

In fall 2018, collaborators in Eldorado and Austin prepared for the implementation of this ambitious, transcontinental project. With funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, EAACONE hired two full-time archival technicians, Letícia Ester de França and Camila Mello de Gomes, to process, digitize, and describe the collection materials. De França is a student and activist from Quilombo São Pedro who has worked with ISA and EAACONE to support the training of quilombola youth leaders. Mello de Gomes is a geographer from Piedade, São Paulo, who has long collaborated with EAACONE and quilombo communities to support human rights, youth education, and the collective mapping of traditionally occupied lands.

In Austin, David Bliss, Digital Processing Archivist at LLILAS Benson, researched and ordered scanning equipment and software to meet the needs of our partners, developing a detailed scanning workflow to guide EAACONE’s team through every step of the digitization process. Itza Carbajal, Latin American Metadata Librarian, developed schemas and templates for the capture of metadata, which is the information displayed alongside archival materials to describe their content and historical context. Carbajal will work with de França and Mello de Gomes to produce their own metadata to describe the contents of EAACONE’s collections. As a CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow in Data Curation, I translated workflows and digitization manuals into Portuguese while serving as a liaison between LLILAS Benson and our collaborators in the Ribeira Valley. In February, Rachel Winston and I traveled to Brazil with Theresa Polk, Head of Digital Initiatives at LLILAS Benson, to deliver equipment and co-teach a week-long seminar on digitization and metadata for EAACONE’s team.

The capacitação (training) was the highlight of my professional career, an exercise in community building, collaborative research, and transnational solidarity. Accompanied by Raquel Pasinato and Frederico Silva of ISA in Eldorado, we met with EAACONE’s team—Sister Maria Sueli Berlanga, Sister Ângela Biagioni, Rodrigo Marinho Rodrigues da Silva, Heloisa “Tânia” Moraes, Antônio Carlos Nicomedes, Letícia Ester de França, and Camila Mello de Gomes—to exchange stories and talk politics over a cafézinho. The group gave us a tour of the archive, displaying historical maps, nineteenth-century land deeds, and photo albums capturing popular demonstrations against the Tijuco Alto hydroelectric dam project during the 1990s. Sueli Berlanga, Sister of Jesus the Good Shepherd nun, attorney, and co-founder of EAACONE, shared pedagogical materials from her early experiences as a community organizer in the countryside, unveiling lessons plans she used to teach literacy and promote conscientização of the historical legacies of slavery in Brazil. Meanwhile, our teams installed equipment and prepared a work station.

Our greatest challenge is to remember all the people whose work has gone unnoticed, those who appear [in the documents] and those who have managed to preserve all this information for so many years, so that today, the archive remains intact to be digitized. — Letícia de França

Among the materials that EAACONE chose to digitize was the Carlitos da Silva dossier. Letícia de França identified her relatives in the newspaper clippings, photographs, and testimonies documenting Carlitos’s assassination in 1982 and the murder trial of Francisco Tibúrcio. In capturing metadata for the dossier, she and Mello de Gomes stressed the importance of recording the names of every quilombola who was affected by the violence and who fought for justice for Carlitos da Silva and his community. “Our greatest challenge is to remember all the people whose work has gone unnoticed, those who appear [in the documents] and those who have managed to preserve all this information for so many years, so that today, the archive remains intact to be digitized,” de França reflected. “Now those documents that capture the history of our struggles can be passed on to the communities themselves.”

Over the next several months, she and Camila Mello de Gomes will continue to scan and create metadata for more than five thousand documents pertaining to the history of the Quilombo Movement in the Ribeira Valley. They will deliver external hard drives to LLILAS Benson, where the Digital Initiatives Team will process the materials and upload them to LADI. The EAACONE Digital Archive is scheduled to launch in November 2019, together with the PCN and Fondo Real de Cholula digital collections. But the real work is what comes next.

An Archive’s Hopes for the Future

From the very beginning, our collaborators have reflected on how best to use post-custodial digital archives to promote international research, teaching, advocacy, and collaboration to defend the rights of vulnerable communities in Latin America. In spring 2019, the Digital Initiatives Team at LLILAS Benson hosted a symposium in Antigua, Guatemala, where representatives from each of our post-custodial partners shared their experiences and plotted future steps.

Camila Mello de Gomes and Letícia de França shared with me their vision for EAACONE. Mello de Gomes proposed the creation of a Center for the Historical Memory of Traditional Peoples of the Riberia Valley, based on the EAACONE archive, which would encompass the collections pertaining to indigenous communities, caiçaras (traditional inhabitants of the coastal regions of southern and southeastern Brazil, descended from Europeans, Indigenous peoples, and Afro-descendants), caboclos (persons of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry), and small farmers. She expressed hope that the center would furnish historical documentation to advance territorial claims and redistributive justice. “As these documents make visible the history of human rights violations that traditional peoples of the Ribeira Valley continue to suffer, I believe that international and scholarly pressure can jointly advance calls for historical reparations and accountability for those responsible for this violence, as well as ensure the care and preservation of an extremely powerful and revolutionary collective memory of the work of MOAB/EAACONE.”

De França expressed hope that the digital archive will serve as a pedagogical resource for preparing the next generation of quilombola activists in the Ribeira Valley. “I hope [the project] draws more young people into confronting the day-to-day challenges that our communities still face. . . . I hope this makes young people more aware of the importance of preserving each document, every single handwritten draft, that tells the history of the struggle of the quilombola people,” she reflected. “All these documents are evidence of the social struggles that we have endured throughout history. Our people never had the support of the rich and powerful. Each victory we achieved was [society’s] recognition of our basic rights. Since we are a humble people, our rights are too often ignored. But with the preservation of this archive, the world will know that every single document that we digitized is a human right that we fought for and won.”

Edward Shore is a historian and human rights activist. His current research explores the longstanding struggles of the black peasantry over land, natural resources, and autonomy in Brazil. He is a postdoctoral fellow at the Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice, working on inequality, human rights, and the future of work. Previously, he was CLIR postdoctoral fellow for data curation in Latin American Studies at LLILAS Benson.

A version of this article was originally published in Not Even Past, a publication of the Department of History at The University of Texas at Austin. Portal is grateful for permission to republish the work in edited form.

Notes

- According to the Society of American Archivists, post-custodial practice requires that “archivists will no longer physically acquire and maintain records, but they will provide management oversight for records that will remain in the custody of the record creators.” Through this model, LLILAS Benson establishes contractual partnerships with smaller, underserved institutions with archival collections, including community archives and civil society organizations based in Latin America. Partner institutions maintain ownership of their original materials and intellectual rights over digital copies, while LLILAS Benson provides funding, archival training, and equipment to produce and preserve digital surrogates. Additionally, LLILAS Benson promotes online access to the collections through the Latin American Digital Initiatives (LADI), a digital repository for historical materials pertaining to human rights in Latin America, which launched in November 2015.

- The first such cohort came together via an innovative project, funded by the Mellon Foundation, to digitally preserve and provide online access to three archives in Central America: Center for Research and Documentation of the Atlantic Coast (CIDCA, Nicaragua); the Museum of the Word and the Image (MUPI, El Salvador); and Center for Regional Research of Mesoamerica (CIRMA, Guatemala).