Harry Ransom Center docents are volunteer guides who lead daily tours of the Center’s exhibitions. In the months leading up to exhibition openings, docents work closely with exhibition curators to gain a more complete understanding of exhibition items and content. The docent training process involves readings, discussion, and intense familiarization with the exhibition.

Cultural Compass shares what excites docents about volunteering at the Ransom Center.

In this edition of our series, meet Carol Headrick, a docent at the Ransom Center for the past 7 years. Headrick, a native Texan, lived in Dallas, west Texas, and southeast Texas before moving to Austin 11 years ago. Before retiring, she taught history, English, and English as a Second Language classes as a public school teacher.

Headrick became interested in volunteering at the Ransom Center after attending several exhibitions. She acted on that interest after attending a UT Odyssey continuing education course that explored the Ransom Center and its collections. It was there that she met Lisa Pulsifer, the Ransom Center’s Education and Public Engagement Program Coordinator, who heads the docent program. From the beginning, Headrick was impressed with Pulsifer’s “innovative, warm, and professional handling of educating docents.”

Who would make up your ideal tour group?

My ideal tour group is curious and eager to ask questions and make comments. This has happened with groups of all ages, from young children to senior citizens.

As a long-time docent, which was your favorite Ransom Center exhibition to research and present to the public?

My favorite Ransom Center exhibition would be The World at War, 1914–1918. In addition to the excellent training that Lisa Pulsifer provided, Jean Cannon, one of the curators, met informally with interested docents and suggested additional in-depth reading of history, fiction, and poetry. It was also fun to meet with Lisa and another docent, Sheila Plank, to brainstorm ideas and prepare materials for young children.

Which Ransom Center collections most appeal to you?

Manuscripts most appeal to me because they show the author’s writing processes. Among my favorite authors at the Ransom Center are Tennessee Williams and David Foster Wallace.

Tennessee Williams’s archive shows that his plays were often revised, most interestingly in collaboration with the director Elia Kazan. Williams and Kazan had to leave out sexually explicit references that were part of the 1947 Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire when they made the 1951 film because of censorship restrictions under the Hayes Code. Evidently America’s movie-going public was deemed less sophisticated than the play’s New York audience.

David Foster Wallace’s archive shows how he researched thoroughly and worked and reworked his novels before publication. His copious handwritten and computer-generated manuscripts contain many revisions and notes to himself, some revealing self-doubt. His library contains many annotated self-help books. These materials perhaps illuminate his fans’ emotional attachment to a writer recognized as intellectually brilliant.

Which of the Ransom Center’s holdings has been your favorite to present?

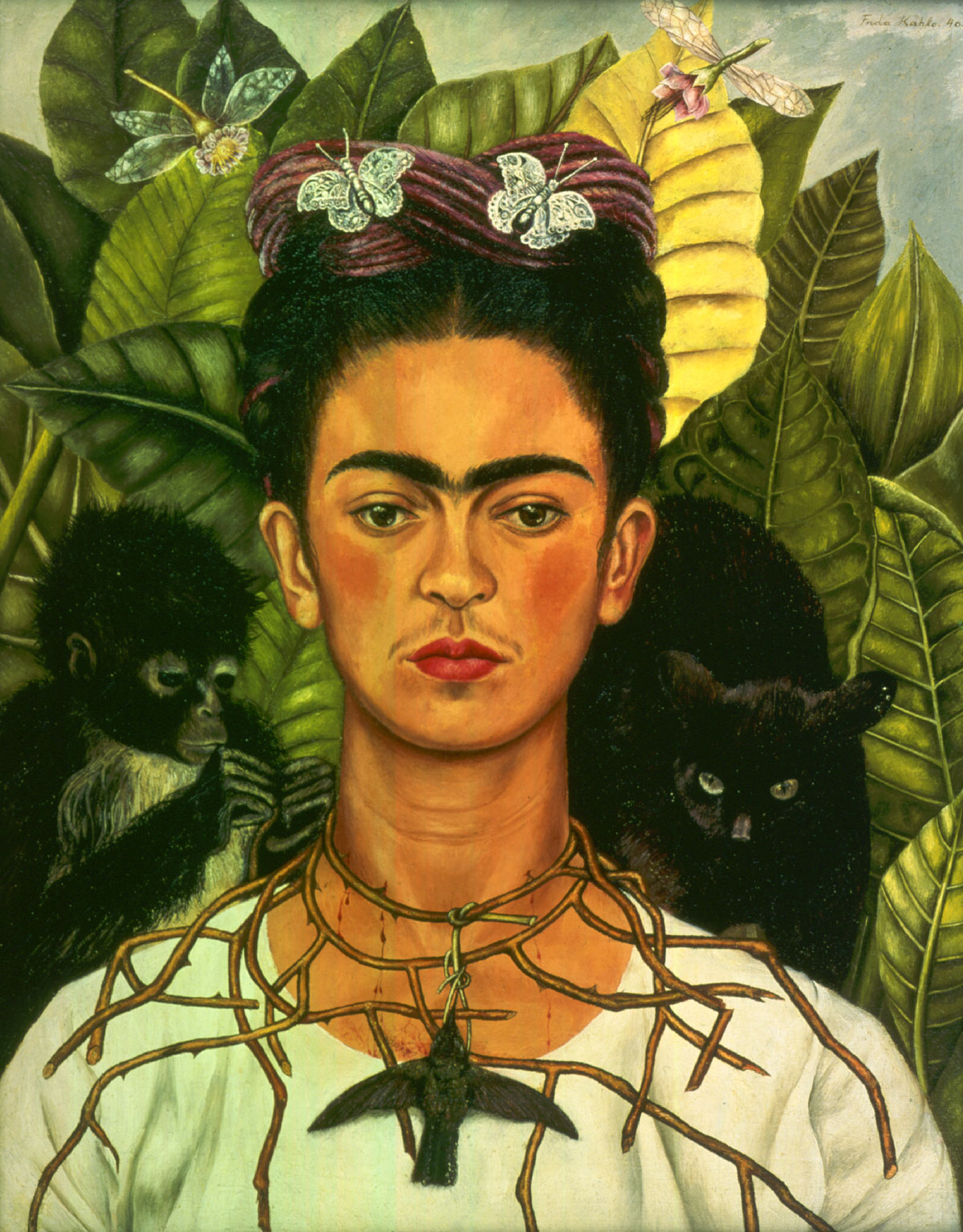

I love to tell visitors about Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird because of the painting’s interesting backstory and its evocative images that spark discussion. Kahlo’s self-portrait arrived at the Harry Ransom Center in 1966 as part of the Nickolas Muray collection. Muray, an Olympic fencer, celebrity photographer, and Kahlo’s lover, bought the painting from Kahlo around 1940, when she was divorced from her husband, Diego Rivera—a difficult time for her financially and emotionally. The compelling images—the thorn necklace, the hummingbird, the expressions of the monkey and black cat, the stylized butterflies and flower-insects—convey her state of mind and invite interpretations from visitors of all ages.

As a docent during the recent exhibition, Frank Reaugh: Landscapes of Texas and the American West, what did you learn about Reaugh when preparing for tours?

The most interesting thing that I learned about Reaugh was his unique teaching method. For 50 summers he took students on sketching trips through Texas and the American Southwest. The “Cicada,” a modified Model T vegetable truck, transported students over narrow, unimproved roads throughout the unsettled plains of Texas and the American Southwest. The accommodations, similar to those of his earlier sketching trips with cattle drives in the early 1880s, offered such adventures as sleeping in bedrolls on ground shared with tarantulas. Reaugh’s trained instructors explained his method to students. They used a viewfinder and specially formulated pastels, manufactured by Reaugh, to paint what the eye saw from top to bottom. Reaugh’s role was to periodically critique each student’s work as master artists had critiqued his work in the Parisian ateliers of Académie Julian in 1889. Reaugh’s method enriched many students’ lives by fostering their love of the land and love of art, and it inspired a few students to establish art careers that surpassed that of their teacher.

What was your favorite item on display in Frank Reaugh: Landscapes of Texas and the American West?

My favorite item is the sketch The Lake—McKavett. It is amazing that Reaugh could capture such details of flora and fauna, and especially the reflection of the lake, in such a tiny plein-air sketch.

The galleries are currently closed while we install Shakespeare in Print and Performance, which opens December 21, 2015. During the run of an exhibition, Ransom Center docents give free exhibition tours daily at noon, Thursdays at 6 p.m., Saturdays at 2 p.m., and Sundays at 2 p.m.