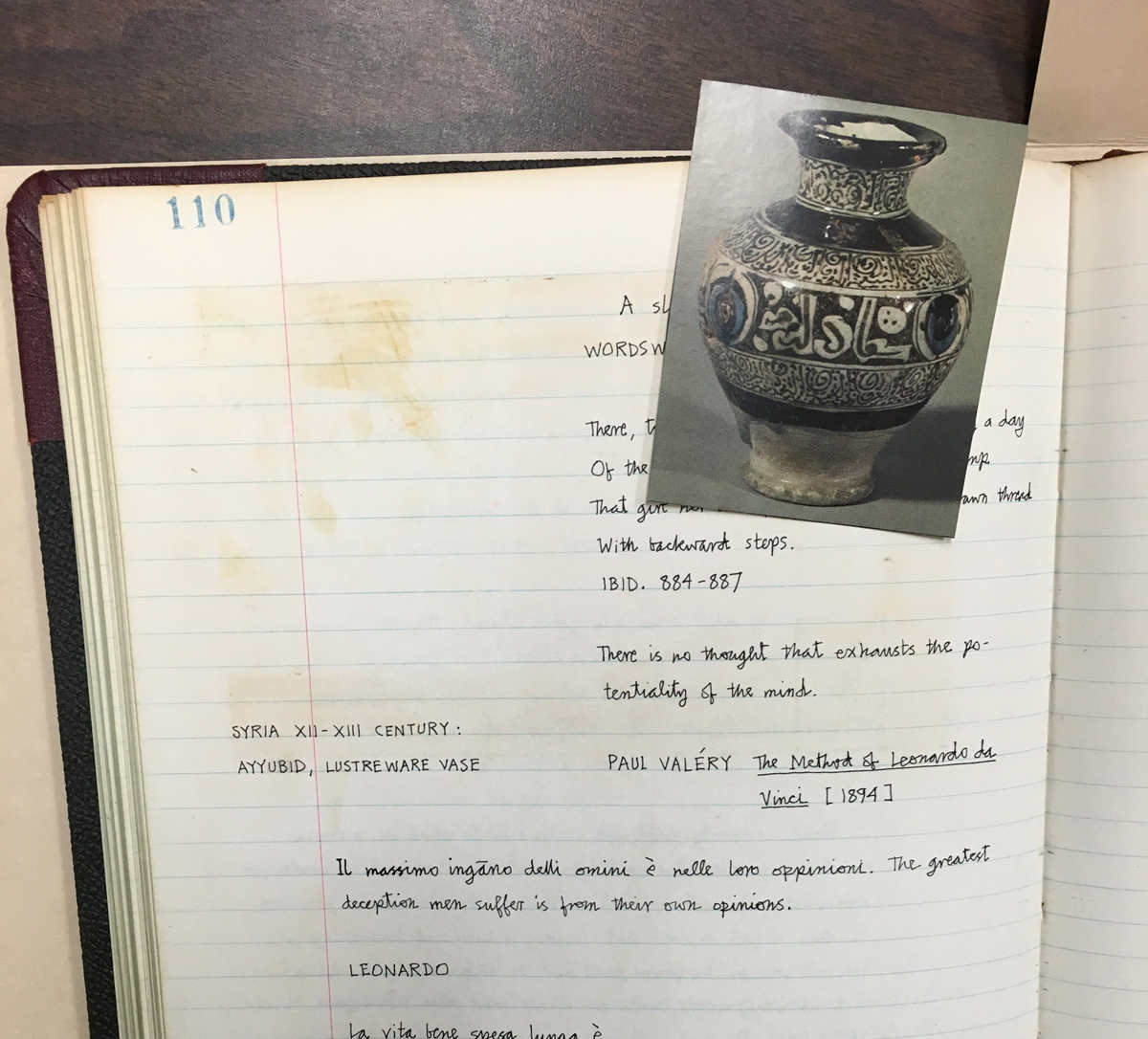

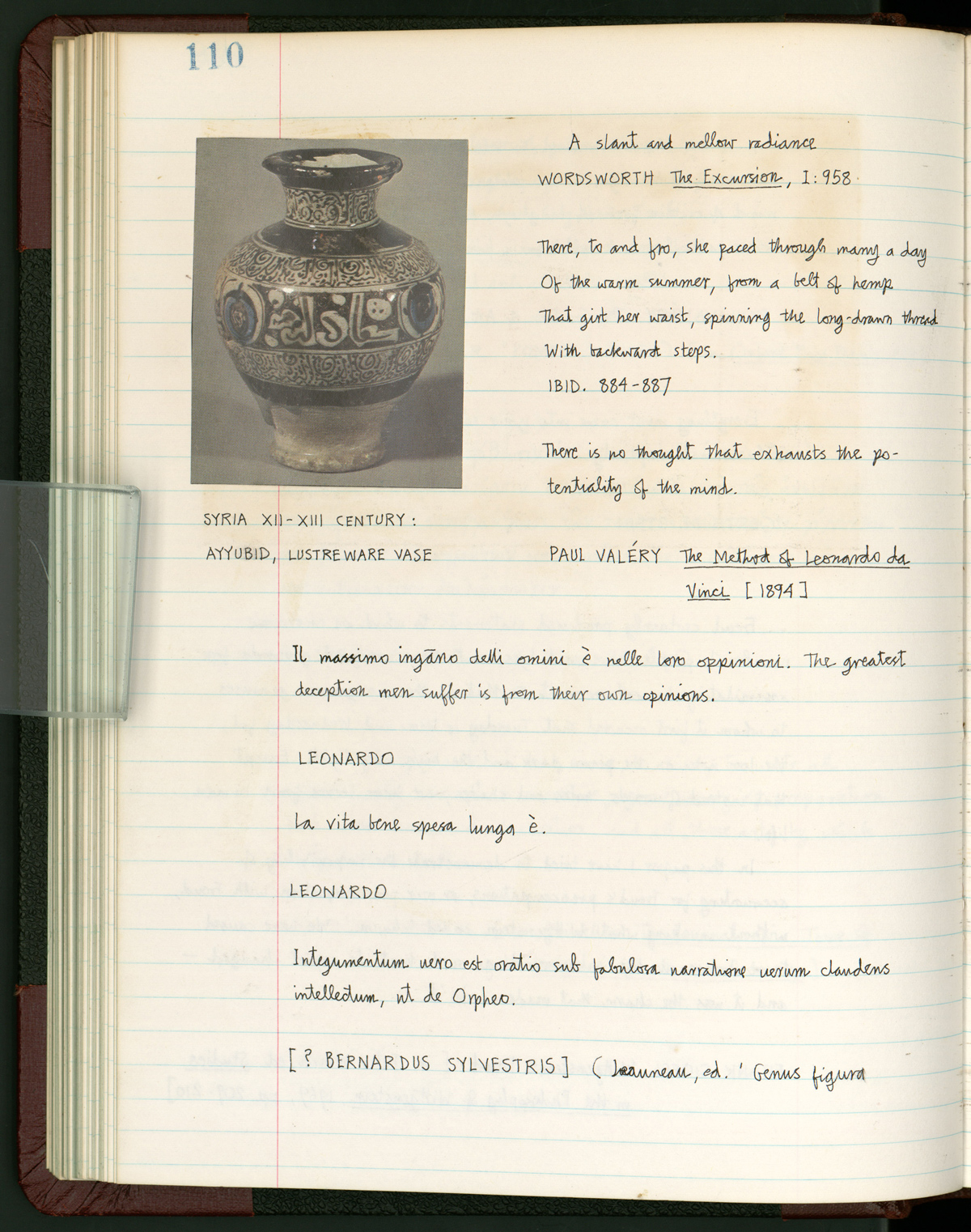

Last year, Ransom Center archivist Richard Workman brought to my attention some journals that he was cataloging as part of the Guy Davenport Papers. Guy Davenport (1927–2005) was an American author, literary critic, and artist. Throughout his adulthood, he regularly kept journals of his day-to-day life and activities (including his feelings about his marriage gone bad, as well as the saga of Humphrey, his cat who went missing for two weeks), but also include entries about his letters to and from the many important literary figures he corresponded with, including Ezra Pound, Hugh Kenner, and Louis Zukofsky. As informative as these entries are, something else that makes these journals stand out is that Davenport illustrated them, mostly using cutouts from magazines as well as his own drawings.

Workman was concerned that some illustrations had detached from the pages. Ransom Center conservators could reattach the illustrations, but the volume posed a daunting task. Other illustrations would likely also detach over time, requiring more treatment at a later date.

We had to determine a way to ensure that loose illustrations did not become separated from the page location within each journal, that each illustration stayed with the proper journal, and that researchers could still access the information within the journals. We made the decision to use a two-step approach to preserving these journals while still providing access.

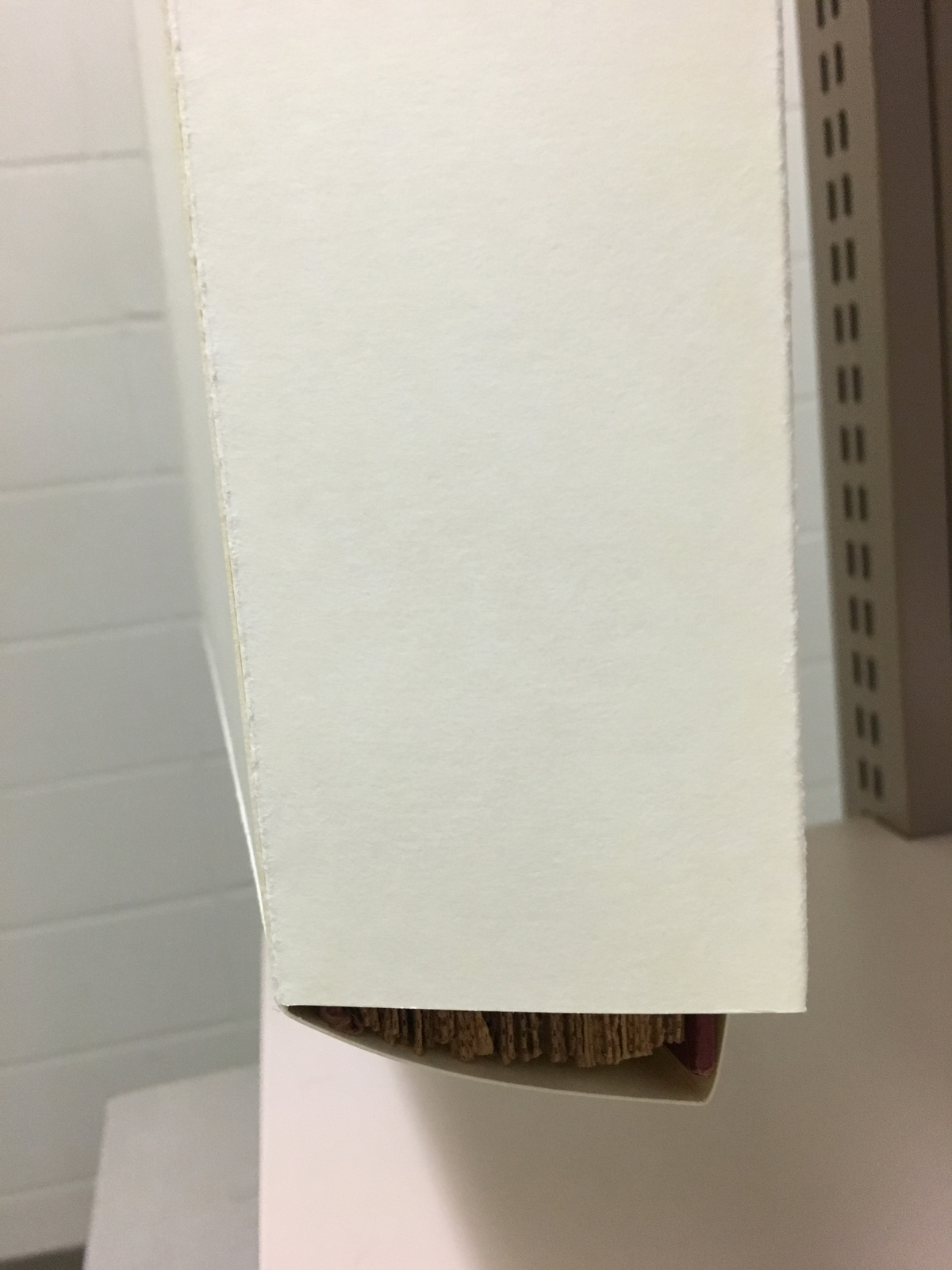

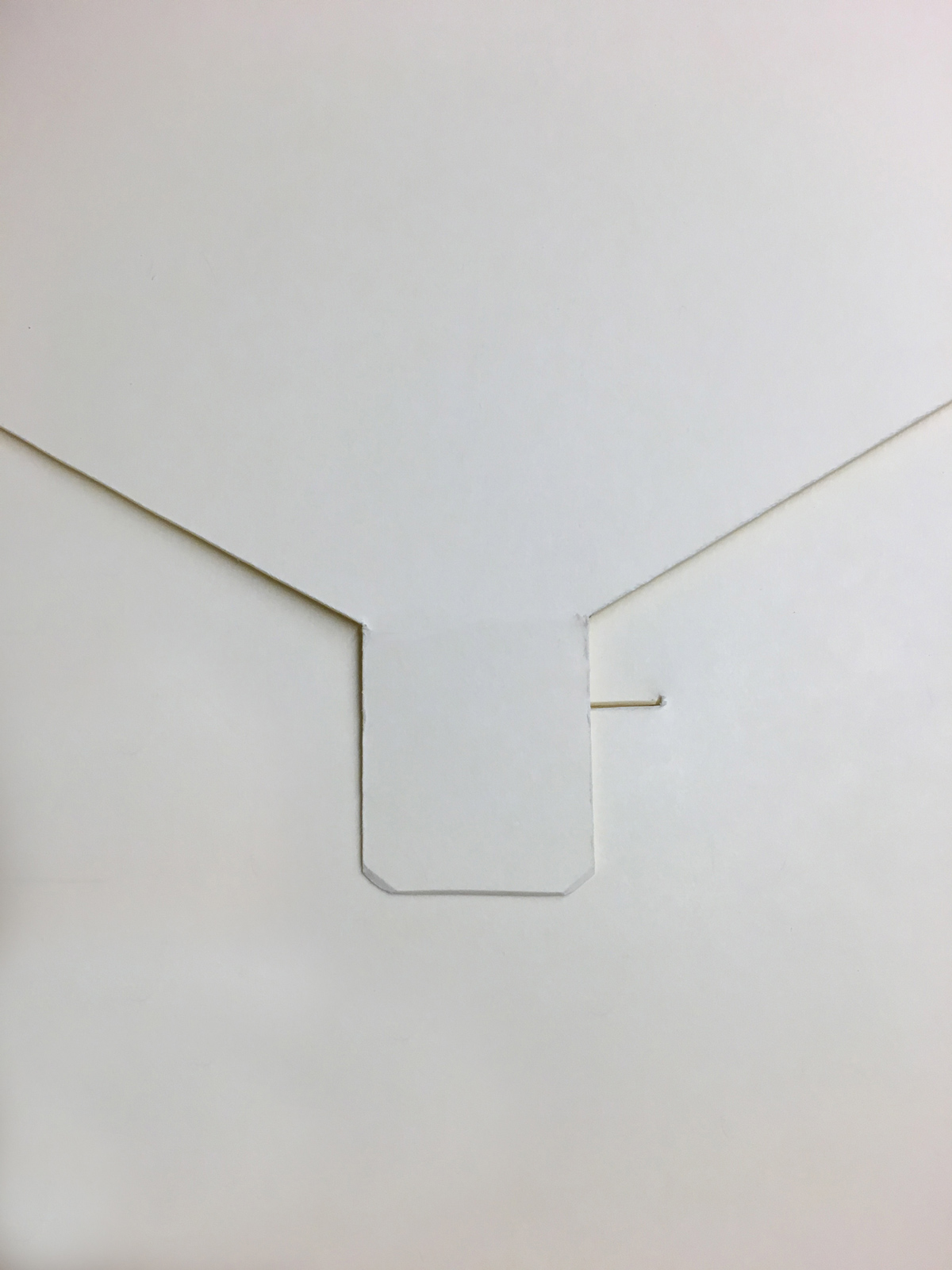

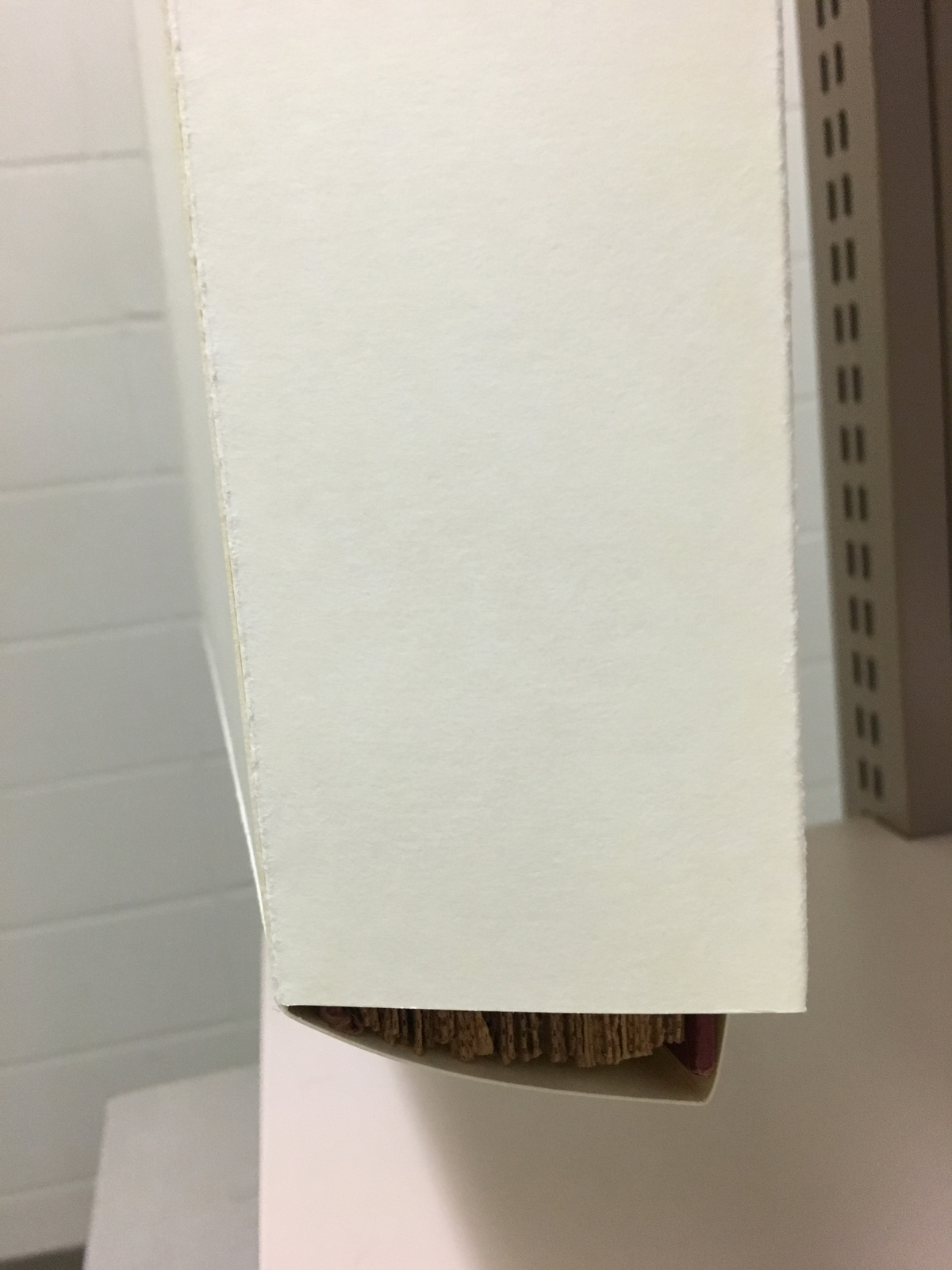

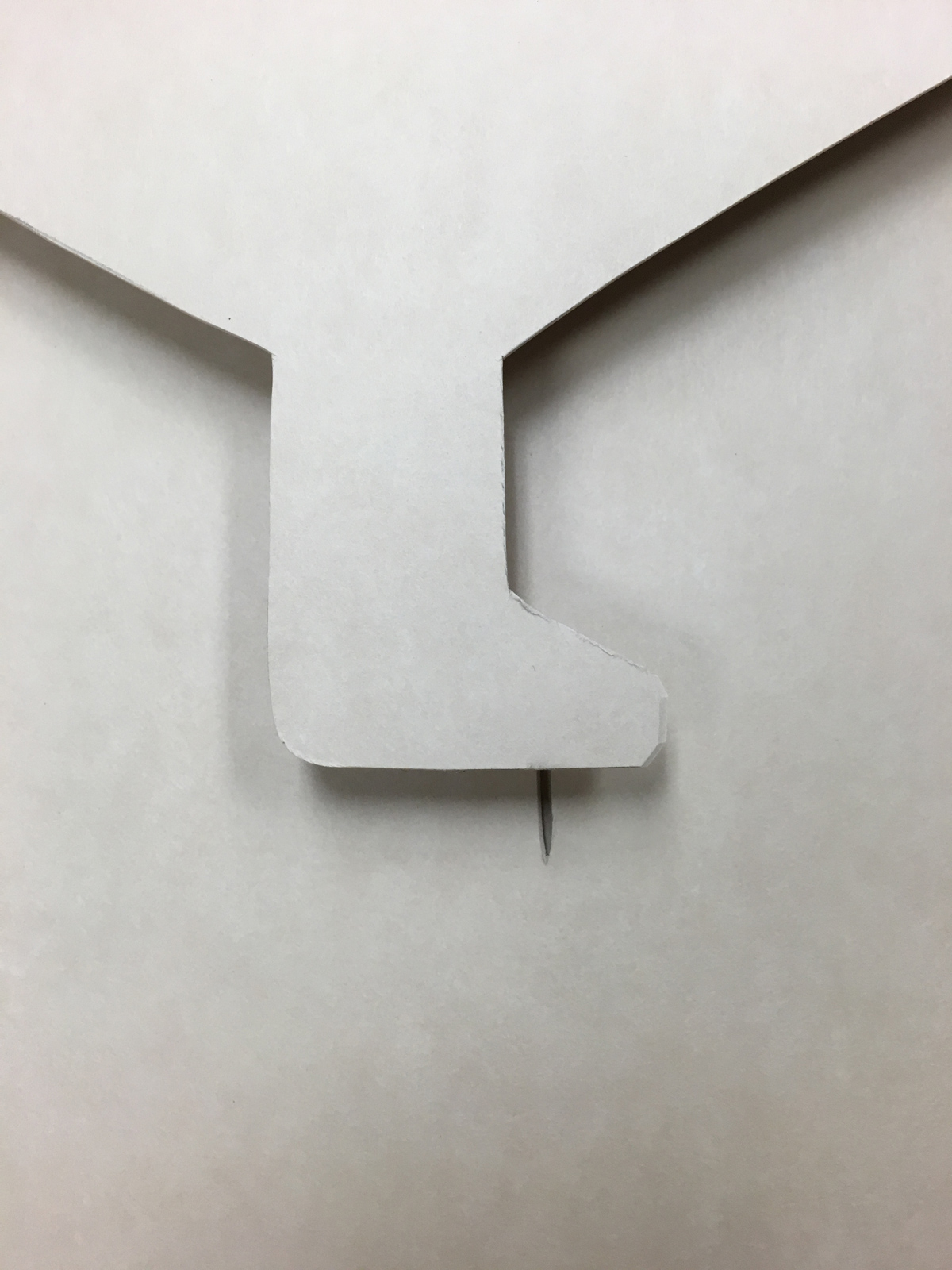

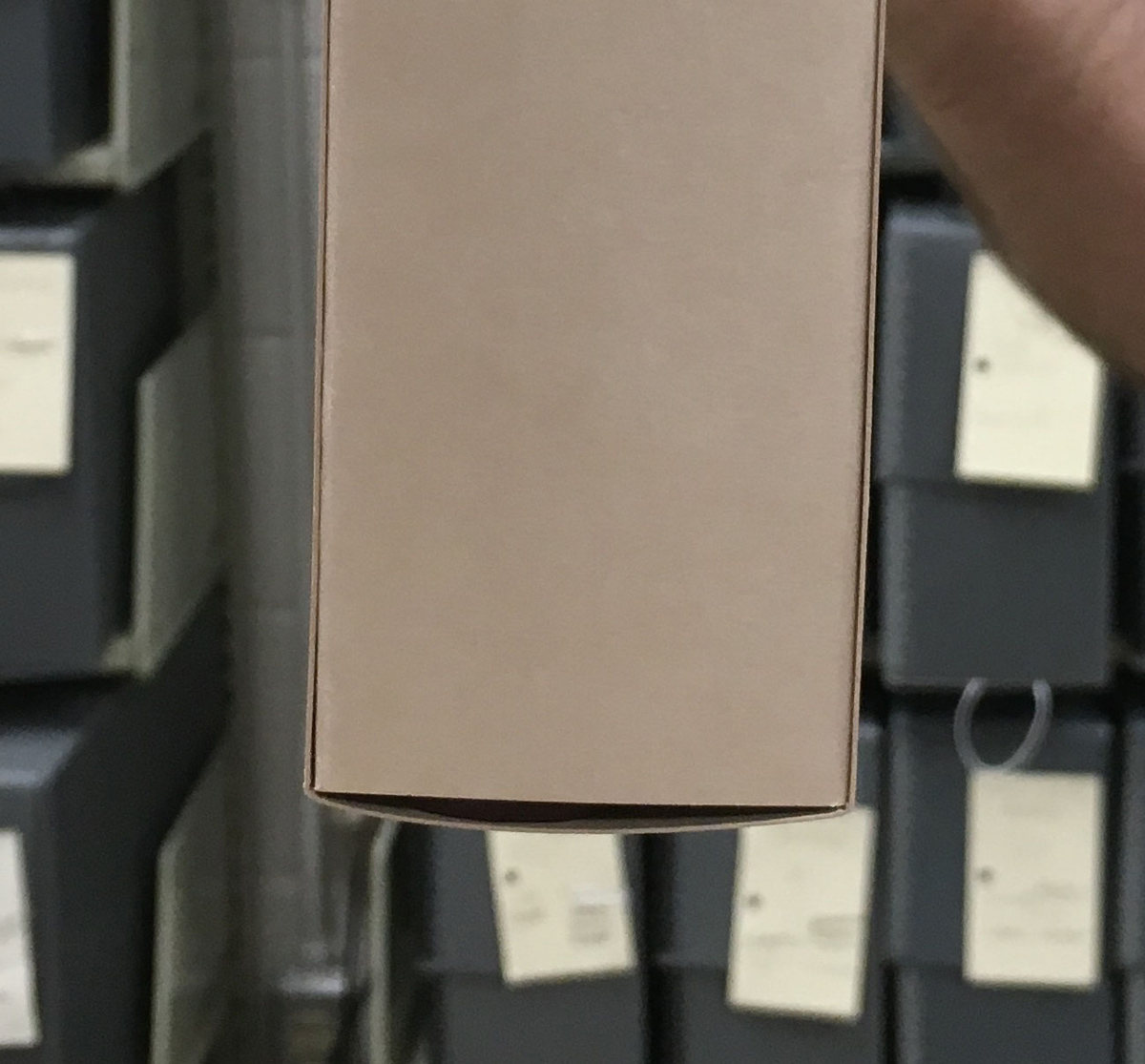

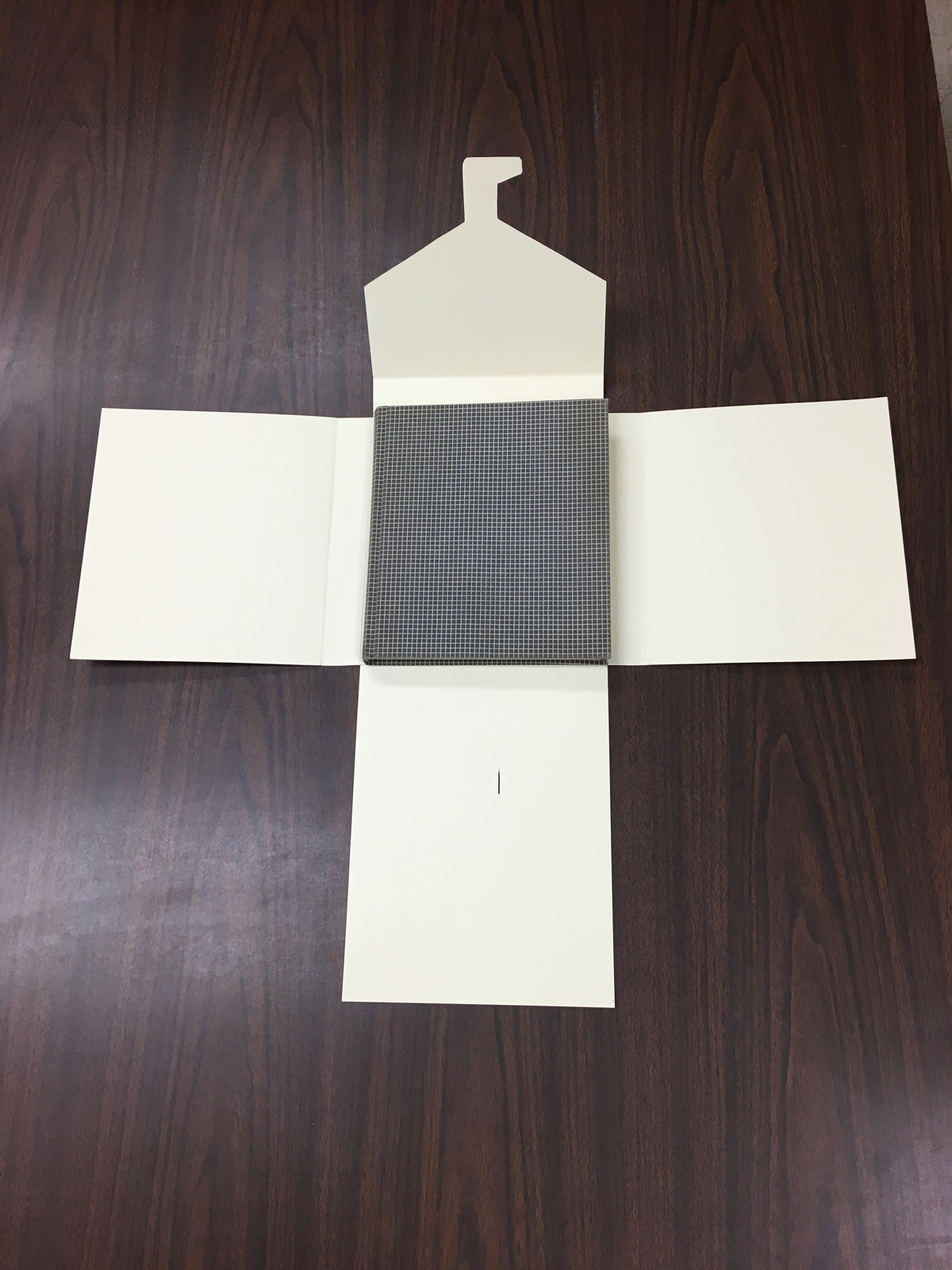

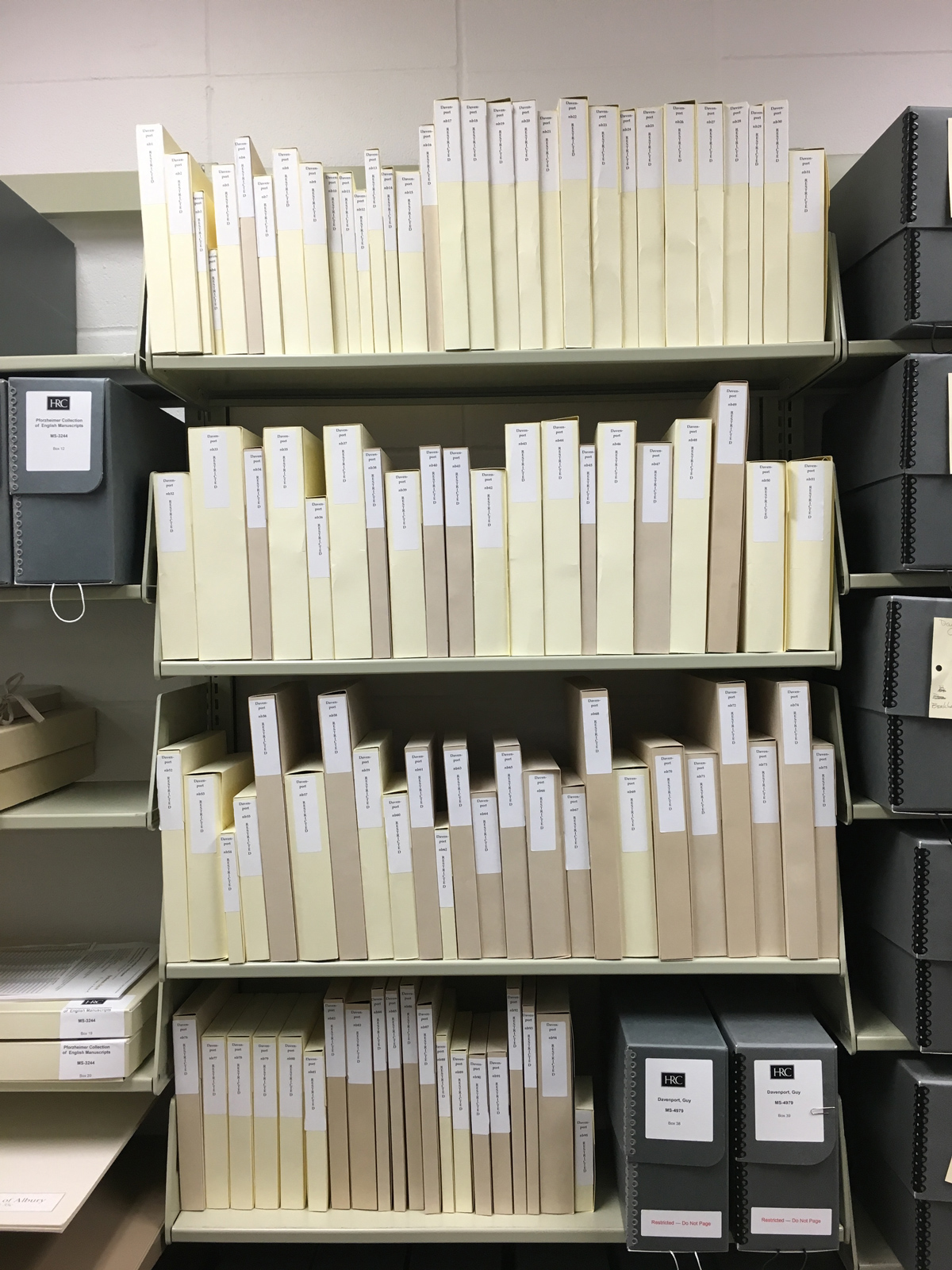

The first step was to make a housing for each journal. We decided to use what conservators call a tux box, a simple four-flap enclosure developed at the Ransom Center. This way, if an illustration came loose from the page, it could not easily fall out of the journal. However, the choice of a tux box presented a new problem: larger books stress the bottom of the box, potentially causing damage to the item or structural failure of the box. The design of the tux box had to be modified in a way to keep the bottom of the box from sagging.

The box closes itself with a tongue and slit. The slit is usually horizontal, allowing gravity to easily pull it down when not supported on a shelf. However, if the slit is vertical, and the tongue adapted to slide into a vertical slit, then the bottom part of the box is held more securely in place.

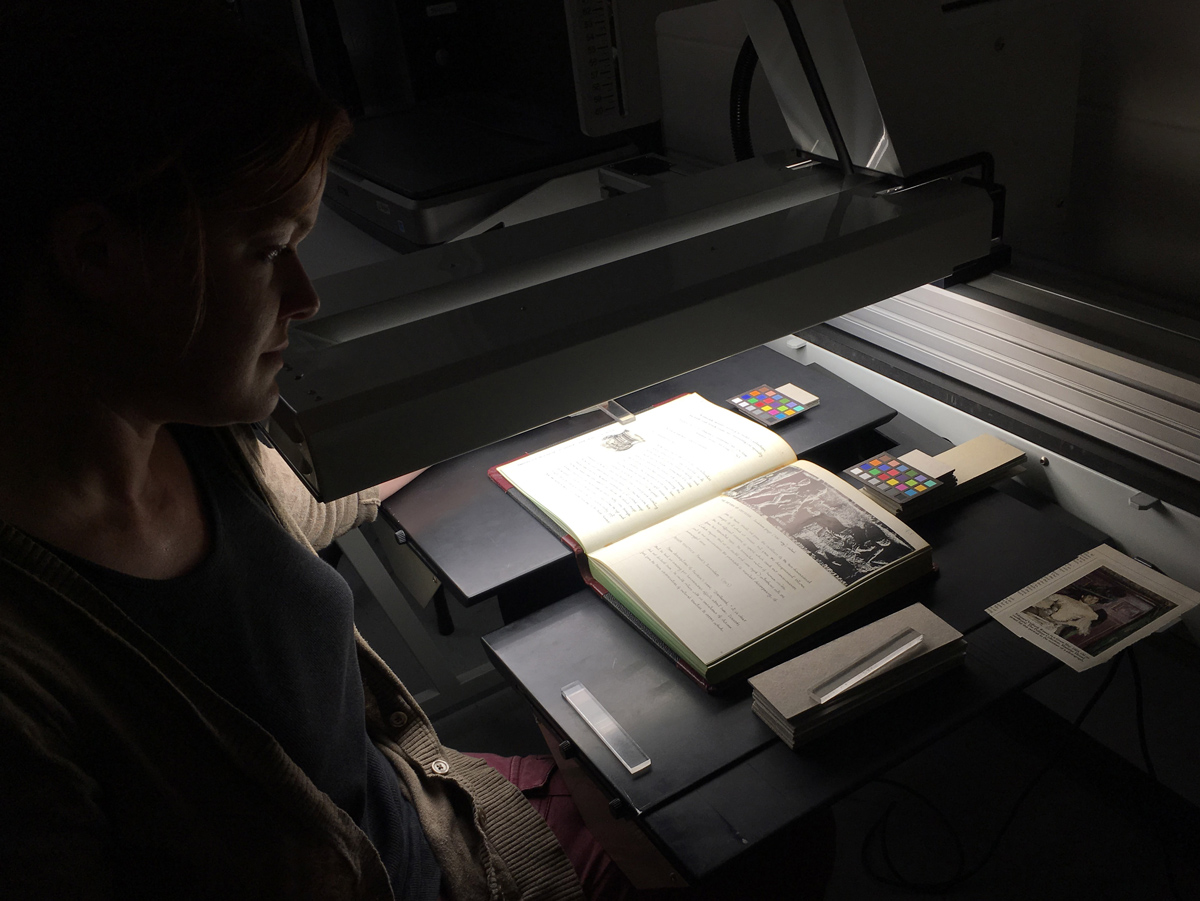

The next challenge was making the information in the journals available to researchers without risking the misplacement or loss of loose illustrations. We decided to digitize the journals cover-to-cover, convert the images to PDF format, and make the digital files available in the Reading and Viewing Room. This way we are able to restrict handling of the physical journals yet still allow access to what is inside them. Another advantage of scanning the journals is that Ransom Center staff now have a record of where each illustration lies within each journal.

Although the Ransom Center has created housings for thousands of journals and scrapbooks, and digitized almost as many, this is the first time we have comprehensively approached a collection of this size with the initial intention of using both methods of preservation. During this project, we housed 95 journals and scanned almost 20,000 pages.

The Guy Davenport journals have been digitized and are available for viewing in the Reading and Viewing Room along with the rest of the Davenport Papers.

Related content

Dear Guy: Letters in the Guy Davenport collection

Receive the Harry Ransom Center’s latest news and information with eNews, a monthly email. Subscribe today.