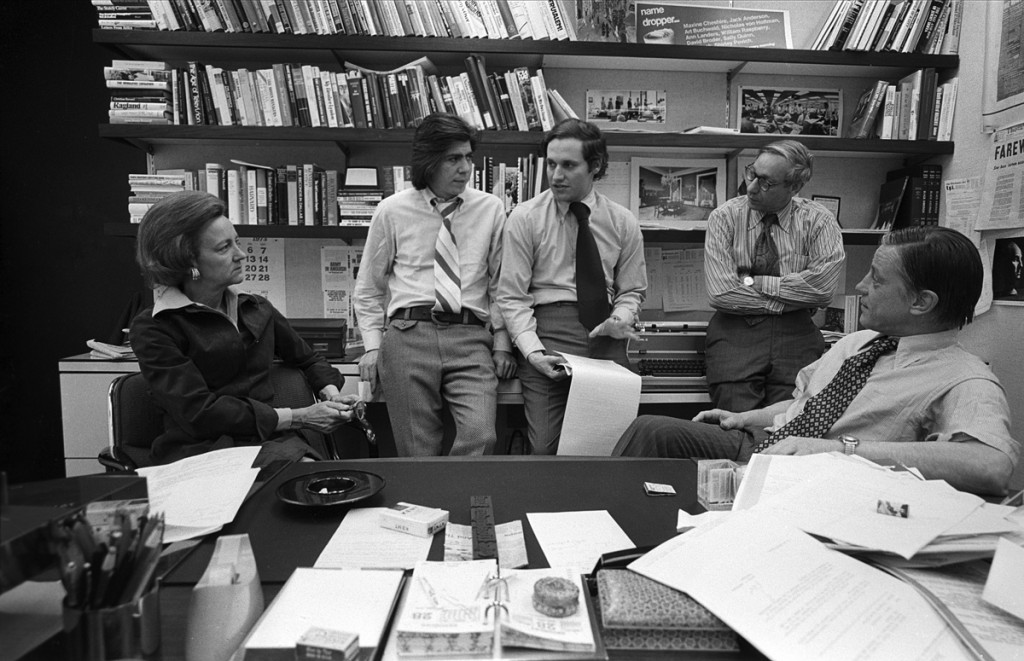

In recent weeks, two separate films have depicted the career of the late Washington Post Executive Editor Ben Bradlee. The HBO documentary The Newspaperman, which premiered December 4, tells Bradlee’s story through a combination of interviews and archival footage.Researchers for the film consulted manuscript materials and audio recordings from the Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers at the Harry Ransom Center. In addition to the documentary, Steven Spielberg’s fictionalized account of the publication of the Pentagon Papers, The Post, starring Tom Hanks as Bradlee and Meryl Streep as Post publisher Katharine Graham, opened later that month.

I had the good fortune to process and describe Bradlee’s papers for the Ransom Center in 2015, and I would like to take this opportunity to share some of the unique materials contained in the archive. Since both the documentary and the feature film discuss the Post’s role in publishing Daniel Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers, I took a second look at the files related to that controversy, searching for original primary source materials not likely to be duplicated in another archive that tell a compelling story. I found letters written to Bradlee from members of the general public expressing their reactions to the Pentagon Papers controversy—one folder of hate mail and one of fan mail, more or less.

Bradlee’s archive is profoundly rich in correspondence; he saved great volumes of letters he received during his career at the Post, not just from friends and colleagues, but also from Post readers, and from those who had never read the Post but saw him on television or read about him in other publications. In those days, public responses to the newspaper were made visible only through a curated selection of letters to the editor published on each day’s editorial page (Bradlee himself did not edit the editorial page and did not select which letters to publish in the newspaper).

Letters from the public that are saved in Bradlee’s archive, however, provide an unmediated expression of what Americans thought about the media at that time. I’ve highlighted some of those voices here, and leave it up to the reader to assess the degree to which American opinion regarding the freedom and responsibilities of the press may have changed in the past 46 years.

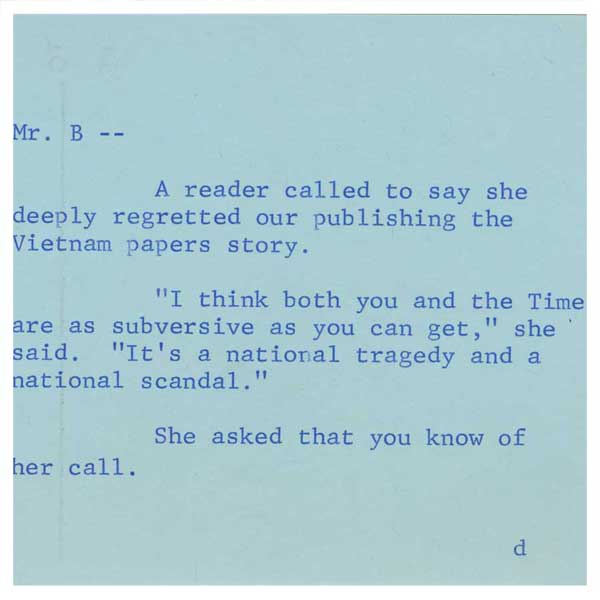

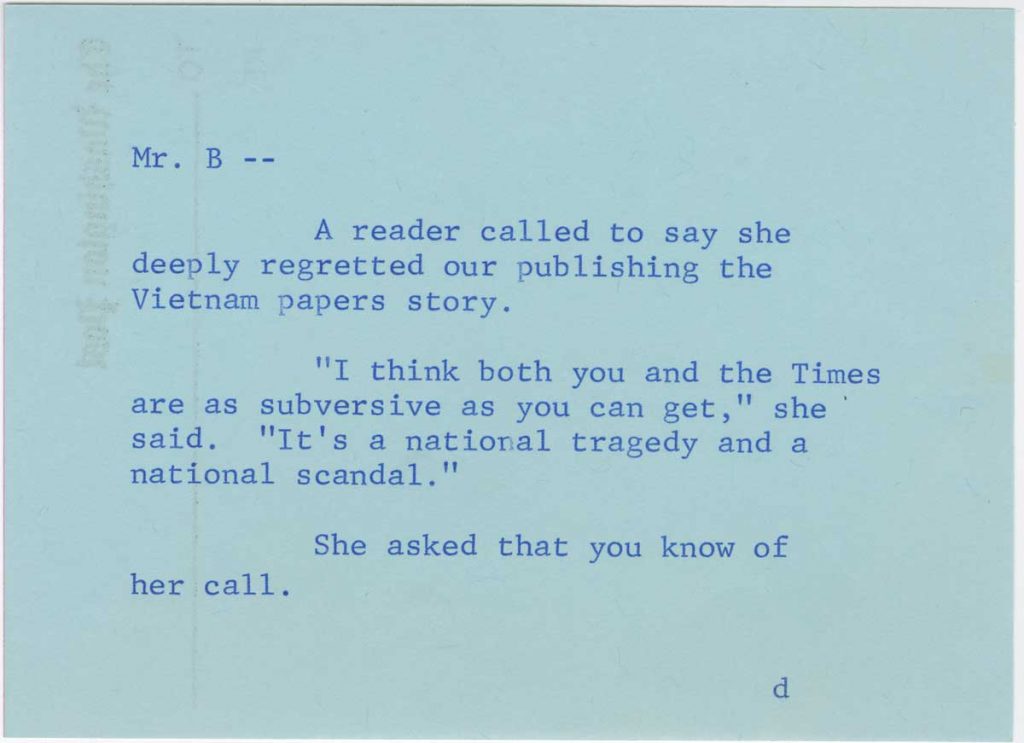

Bradlee’s original files divided the letters he saved regarding the Pentagon Papers into two folders, labeled “Public reaction (negative)” and “Public reaction (positive).” Several writers in the “Public reaction (negative)” folder were disappointed in the publication of information that they believed would compromise national security interests or possibly even put American lives at risk.

Hate mail

One correspondent from Dallas who wrote to Max Frankel, editor of the New York Times, after viewing an NBC News special on the Pentagon Papers (copying Bradlee on the letter), “You spoke of the First Amendment and the privileges of the New York Times to print the news whatever the consequences…Any given number of additional secret document printing for public consumption and there could possibly be no more First Amendment, no more democracy, and yes—Mr. Frankel—no more New York Times…This is the type of action that is destroying the United States from within and to say the very least causing the public not to know what to believe.”

A writer from Troy, New York who watched the same program wrote, “I believe the press has too much power at times and in cases that concern vital information or information concerning our government…I really felt ashamed of you and Mr. Frankel and am sorry I watched the program, having the feeling that you were not sincere—just not interested in what your country might feel vital information nor how you hurt people now living or dead…The news must come first before country or people must be your motto.”

Other correspondents felt that the Times and the Post had acted immorally by publishing documents that Ellsberg had copied illegally. A minister based in Washington, D.C., wrote, “It is my own personal hope that the government of the United States will indict and prosecute to the fullest extent not only the thieves or thief, but also the representatives of the newspapers and anyone else involved.”

Several writers argued that by publishing the Pentagon Papers, newspapers were furthering the aims of Communists: “The NY Times might as well be a subsidiary of Pravda,” concluded the sender of one anonymous postcard. The “Public reaction (negative)” folder also contains some examples of hate speech. A Post reader from Alexandria, Virginia, wrote that the Pentagon Papers were “All a ‘Jewish’ conspiracy to take over America. To the concentration camp with treasonable and disloyal bas—-…and others of your paper that are part and parcel of this conspiracy. Hitler was right on this score…” Out of about 50 letters in the “Public reaction (negative)” folder, three are anti-Semitic in content (two from the same correspondent in Alexandria).

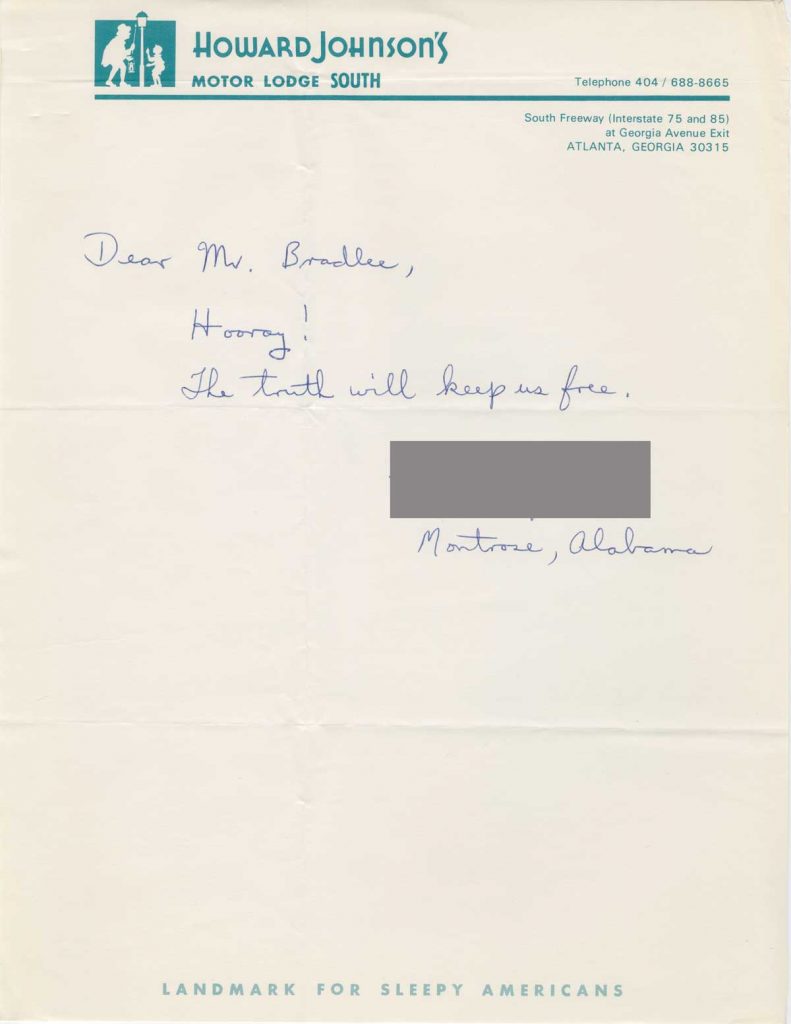

Fan mail

Bradlee’s “Public reaction (positive)” file is slightly smaller than the file of negative responses, containing approximately 40 letters. There are a few letters of support from Bradlee’s friends and several letters and telegrams from journalists in the United States and overseas. Many letters written to Bradlee by members of the public stress the importance of a free press that is independent of political control. A viewer of the NBC Special Report from Pittsburgh wrote, “I and many Americans are very very wary of politicos or their hirelings, no matter to which political party they make their genuflections, of making the omnipotent decisions of which piece of truth will be or will not be injurious to the citizenry of the land…The dangers to this democratic republic of an ill-informed or misinformed populace far outweigh the ‘horrendous’ dangers to national security and defense put forth by those on the program who urged that the public be kept in the dark.”

Another viewer from Spokane commented, “At such a frightening time in our history, you and Mr. Frankel afforded us our most refreshing hope for our future and the future of our country that we have encountered in many years. May we offer our support along with our appreciation for your courageous stand against government infringement (at least) on the freedom of the press to supply us with the truth.” A viewer of the NBC special from Cincinnati wrote, “You did a great job in expressing my viewpoint, and I’m sure of the ‘silent majority’ on the right of the people to know about Vietnam. It’s past time and you have my absolute gratitude!”

“Thank you for standing up and being counted when so many people in ‘power’ positions seem to pass the buck and compromise themselves. Perhaps there’s more hope for this country than I realized. I rejoice in your courage and real patriotism,” commented a viewer in Minneapolis.

One correspondent from Beverly Hills sensed that the Nixon administration’s attempt to prevent the Pentagon Papers’ release could presage future abuses of power: “Consider now the President…what risk does he have to weigh? Suppose, as happened here with the Pentagon Papers, three tiers of courts slap him down. What punishment does he suffer for his attempt at an illegal exercise of power?…what restraint is there on him from doing anything he pleases and seeing if he can get away with it? The situation is tailor-made for every chief executive to try out wider and wider powers. The temptation is too great that he can’t help himself.”

And in contrast to those writers who criticized Bradlee for publishing illegally disseminated documents, a correspondent from El Paso wrote, “Mr. Ellsberg should be cited as a hero for literally forcing the government to be honest in spite of itself…I believe the laws broken by Mr. Ellsberg in taking the documents and disseminating them to the press are, at best, laws that need to be broken. Secrets can damage us far more than the truth.”

The last word

I conclude by quoting some of Bradlee’s words from a letter sent in response to a Post reader from Arlington, Virginia, who criticized the newspaper’s publication of diplomatic documents from the Pentagon Papers in 1972. She commented, “I love my country and support our President and the good men around him in government. I’d like to see the Post take a positive step in the right direction for a change.”

Bradlee replied, “None of us has a corner on love of our country or on hope for positive change. You and I perhaps disagree only on the role of newspapers in expressing that love and making this earth ripe for that hope. I begin with the conviction that an informed people, a people truly informed by a press totally free of allegiance to anything but the truth, is the foundation of our democracy.”