Leslie DeLassus is a film historian and instructor with a Ph.D. in Film Studies from the University of Iowa. While working on her Ph.D, DeLassus came to the Ransom Center to research early film special effects innovator, Norman O. Dawn, and his groundbreaking work.

Norman O. Dawn was was a relatively obscure yet historically significant early special effects cinematographer, inventor, artist, and motion picture director, writer, and producer. He invented the “glass shot” application to motion picture, and was the first director to use rear projection in cinema.

Ahead of her free lecture on Thursday, May 16, at 7 p.m. at the Ransom Center, DeLassus answered a few questions about Dawn and her time here.

Jared Neuharth: What attracted you to Norman O. Dawn?

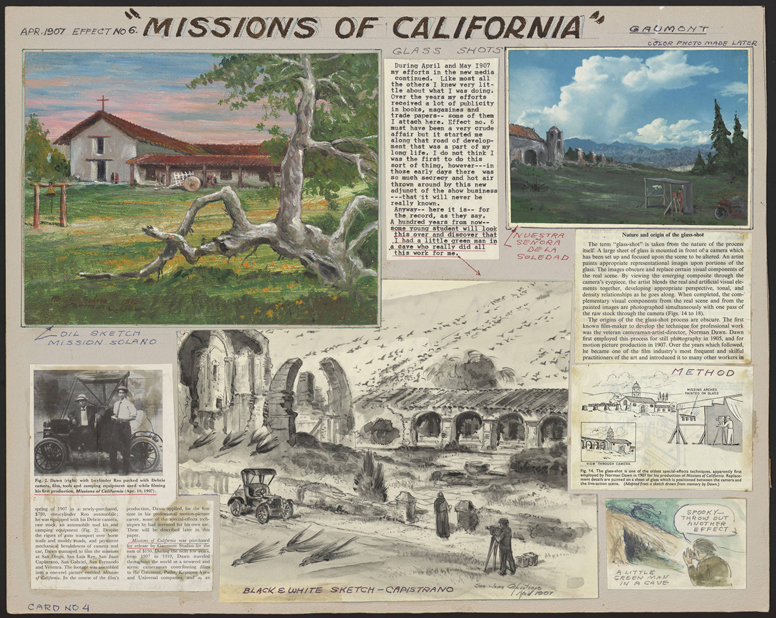

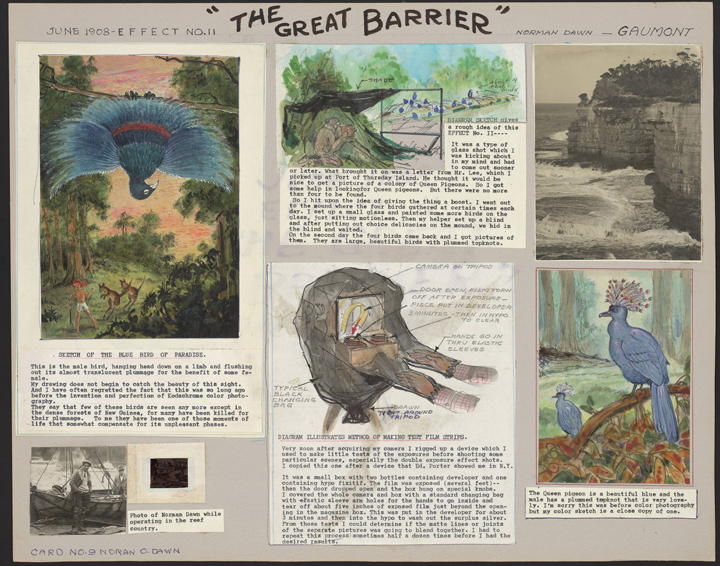

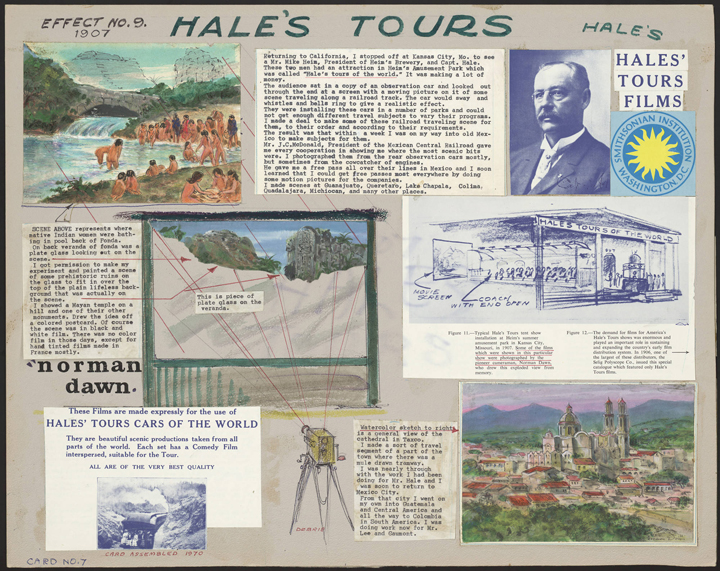

Leslie Delassus: The collection material itself is spectacular. Film Curator Steve Wilson introduced me to the collection while I was an intern at the Ransom Center in 2004. I was drawn in by the collection immediately, which consists of 164 poster-sized collage cards that each explain the composite imaging processes Dawn used to produce special effects scenes for a specific film. Not only are the cards mesmerizing collages of visually stimulating archival material, they unearth a vault of ephemera related to more than 75 films produced between 1907 and 1950, which are either considered lost or have since fallen into obscurity. I completed a dissertation based on these materials in 2016 and still have not exhausted their historical significance.

Could you explain how Dawn’s “glass shot” was executed?

The glass shot process involves shooting a live-action scene through a large plate of painted glass. In the resulting composite image, the painted portion of the glass appears consistent with the live-action scene. Often times, Dawn used this method to visually restore the edifice of a significant structure, such as the Port Arthur Penitentiary, which had to appear to be a fully-operational prison during the production of Dawn’s 1927 Australasian Films historical epic For the Term of His Natural Life, despite the fact that the prison was in ruins at the time. The glass shot process was also used to increase production value by adding spectacular elements to a live-action scene, which would otherwise be too costly and dangerous to shoot.

How different would movies be today if Dawn hadn’t invented these techniques?

Dawn’s composite imaging processes made spectacular scenes economically feasible in studio-era commercial feature film production. Producers were able to include natural disasters, catastrophic accidents and picturesque scenery without exceeding production costs, which ultimately allowed for the elevation of B-picture genres such as science-fiction, horror, and adventure serials in more contemporary commercial Hollywood films such as Star Wars IV: A New Hope and Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The extent of Dawn’s contribution to film history extends beyond the innovation of special effects processes. Dawn participated in the relocation of the film industry to Hollywood from New York and New Jersey where the Motion Picture Patent Company monopolized all resources for film production, distribution and exhibition by smuggling a Debris camera into the U.S. from France and shooting travel and scenic footage for film producer Arthur Lee and for an amusement park ride that simulated train travel called Hale’s Tours of the World.

Even though the film Dawn was working with is now outdated, are any of his techniques still applicable?

Dawn made significant innovations to the multiple exposure process, which is essentially the predecessor of contemporary digital effects that combine live-action scenes with computer-generated imagery. The main difference is that the multiple exposure process relies on imagery such as matte paintings, while digital effects rely on computer-generated imagery.

Of Dawn’s techniques, do you have a favorite?

I love the in-the-camera matte double exposure, which involves the compositing of two separate exposures into the same shot. I find it fascinating that the first exposure must be absent during the second exposure in order to create the illusion that two spatially distinct image elements are visible from a single vantage point.

Did you make any surprising discoveries while researching the Ransom Center’s collections?

While I was doing research on For the Term of His Natural Life, I noticed that one of Dawn’s cards titled “October 1908, Subject no.12, Glass Shot” contains a frame enlargement of a glass shot of the Port Arthur Penitentiary with what appears to be two costumed actors from For the Term of His Natural Life. An excerpt positioned underneath the frame enlargement from film historian Raymond Fielding’s book The Techniques of Special Effects Cinematography cites the image as an enlargement of a glass shot from a 1908 nitrate print of a scenic film Dawn shot in Tasmania. I found in letters of correspondence between Fielding and Dawn a letter to Fielding from a film historian in Australia questioning the labeling of the frame enlargement. In the final piece of correspondence concerning the possible mislabeling of the frame enlargement, Dawn confirms the 1908 date of the glass plate instead of the enlargement.

This strange inconsistency left me with two options: 1) observe the 1908 date provided by Fielding and Dawn, which prompted the ludicrous fantasy of Dawn insisting that the costumes for the cast of For the Term of His Natural Life must match the two figures in the 1908 glass shot; or, 2) allow the discrepancy to remain and examine possible consistencies that would permit such a mislabeling. While I was doing this kind of research, I felt somehow outside of linear time, like a double agent of history with one foot stuck in 1908 and the other in 1927, which became an important theoretical problem that I tried to address in my dissertation.

Related content

View Norman O. Dawn’s collection