Leslie DeLassus is a film historian and instructor with a Ph.D. in Film Studies from the University of Iowa. While working on her Ph.D, DeLassus came to the Ransom Center to research early film special effects innovator, Norman O. Dawn, and his groundbreaking work.

special effects

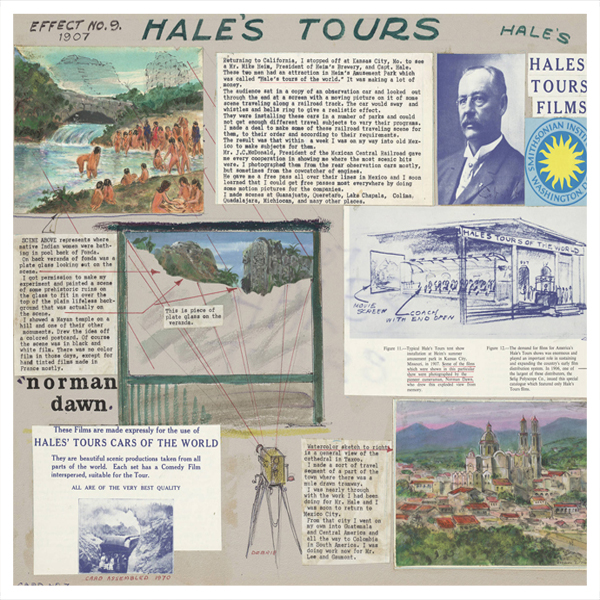

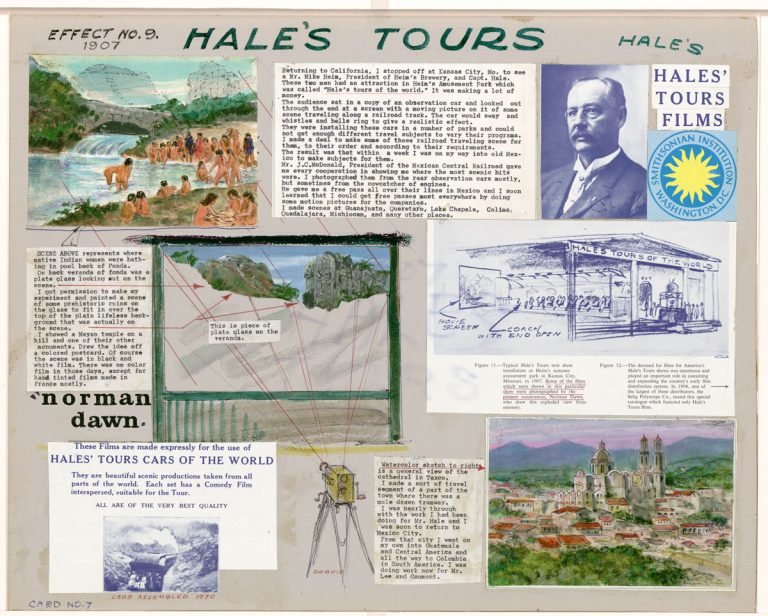

New digital collection highlights work of early special effects creator Norman Dawn

The Ransom Center recently launched a new platform of digital collections on its website, which includes the Norman O. Dawn collection. More than 240 items from that collection, including the cards highlighted in this blog post, can be viewed on the new platform. Leslie Delassus worked as a graduate… read more

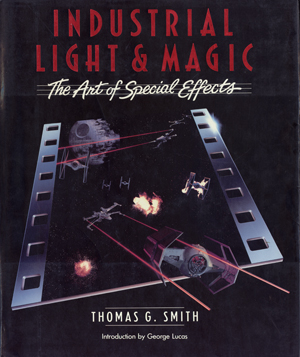

Q and A with Tom Smith

The archive of visual effects producer Thomas Smith has been donated to the Ransom Center. Smith worked on the special effects for such films as Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. (1982), Star Trek: The Search for Spock (1983), Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), Indiana Jones and… read more