A Q & A with Dr. Bruce Hunt about the Blaeu World Map

In recent blog posts, we examined the science behind the Blaeu World Map and took a deep dive into the conservation in progress to prepare the massive 371-year-old map for public display.

But how did the Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula (Blaeu World Map) come to be, and what prompted a family of herring merchants to become the leading cartographers, globe makers, printers, and publishers of their age? Who was the Blaeu World Map created for, and was it actually used for navigation?

We recently spoke with The University of Texas at Austin Associate Professor of History Bruce Hunt to find out more about the history of this incredible map.

Looking at the map, there are three world systems there, including the Tychonic world system. I was hoping you could give us some insight into Tycho Brahe and his influence on the Blaeu family.

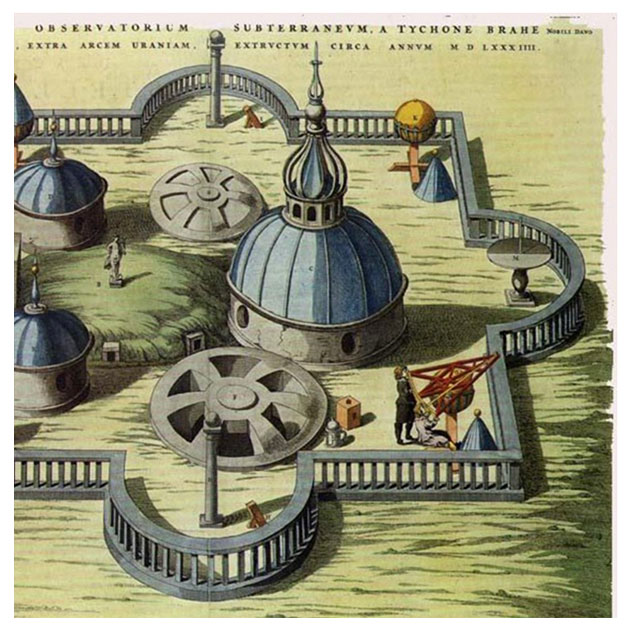

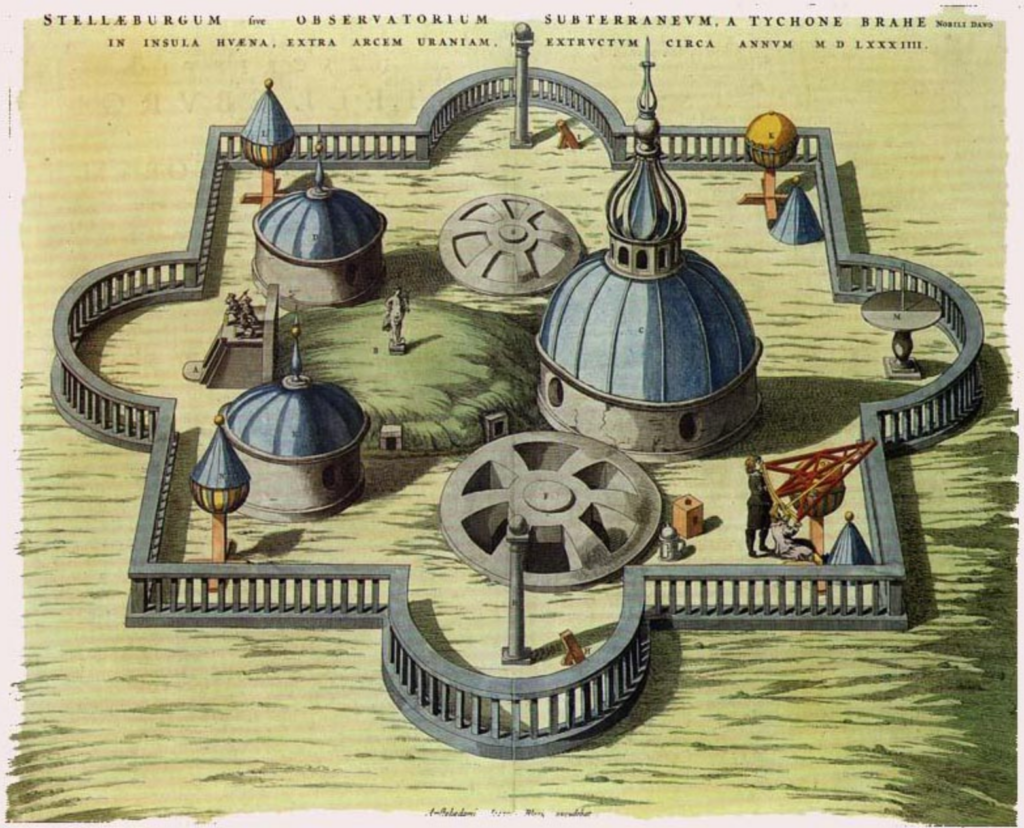

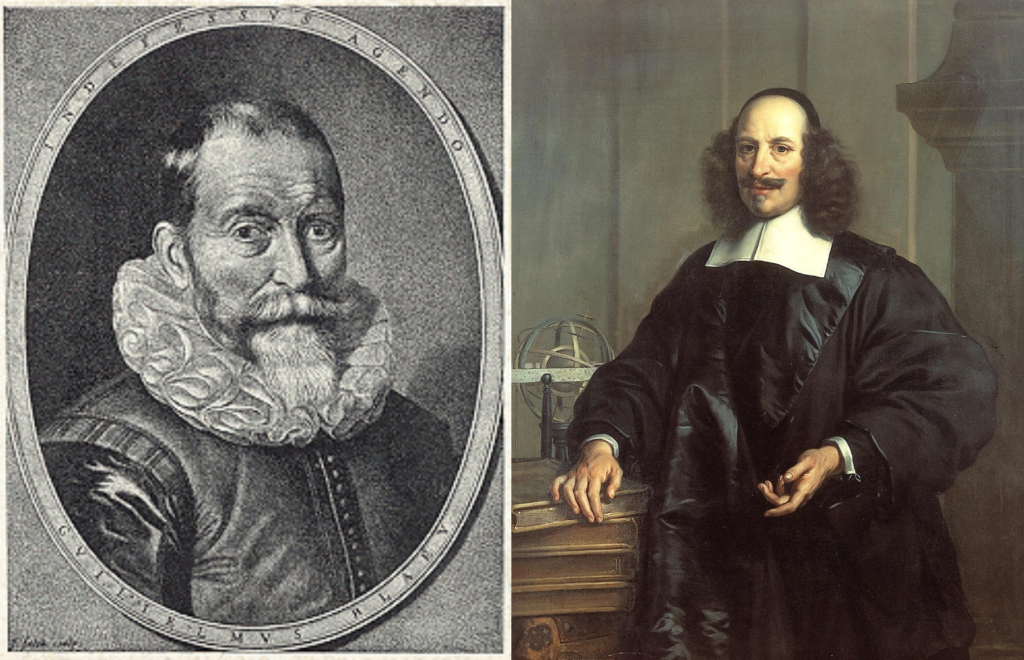

BRUCE HUNT: Absolutely! Tycho Brahe was a very high-ranking Danish nobleman. His relatives were basically equivalent to the king, and he took a great interest in astronomy. In the 1570s, the king of Denmark at the time rewarded him by making him the feudal lord of the little island of Hven, which is now a part of Sweden. He was there from the late 1570s to the late 1590s. That was the greatest pre-telescopic astronomical observatory in the world, and he made the best observation of the heavens. Willem Blaeu, the father of Joan Blaeu, who made this map, spent about 6 months on this island with Tycho.

What brought him to the island?

HUNT: He was very close with Tycho. Blaeu was there from the end of 1595 to the first half of 1596 and Tycho introduced Willem Blaeu to astronomy and cartography. How he went from being a herring merchant to an astronomer and mapmaker is kind of mysterious to me, but he got interested in the subject and arranged some time to go be an assistant to Tycho.

Did Joan Blaeu, Willem’s son, interact with Tycho at all?

HUNT: No, he had no direct involvement with Tycho. Tycho died in 1601 after he went to work for the Holy Roman Emperor in Prague as his astronomer. Willem Blaeu, after his encounter with Tycho, goes back to Amsterdam and sets himself up as a mapmaker, globe-maker, printer, publisher, and astronomer [in 1598].

When was it that Joan Blaeu got involved in map-making?

HUNT: When Willem Blaeu died in 1638, his son Joan who had taken up the same line of work, continued the business for some time afterward, and then printed the Blaeu World Map in the Center’s collection about 10 years after his father’s death. He also published a gigantic atlas [known as the Atlas maior], it was the biggest printing/publishing project of the 17th century, just gigantic, 12 volumes [in the French version; others were between 9 and 11 volumes]. Joan Blaeu’s atlas included very nice illustrations of Tycho’s island, his instruments, and his observatory. These are the ones I show in my classes when they’re talking about Tycho and astronomy. Joan Blaeu becomes one of the leading cartographers and map and globe publishers, and this gigantic map, I mean, it’s huge, is one of his grand projects.

Since the Blaeu World Map was a gift for the Spanish ambassador Gaspar De Bracamonte y Guzmán and not for navigation, are the constellations still as accurate?

HUNT: It’s not like someone would be taking this on a ship and consulting it. No, it’s far too large for that. But the same information that you would use to depict the positions of features on the surface of the Earth and to depict stars and constellations, would be used for making practical and smaller maps.

I noticed that California isn’t connected to North America on the Blaeu Map. Why is that?

HUNT: You will find that [some] maps in the 17th century, show California as an island. If you travel up the Gulf of California, near Baja, you can go up a long way [before seeing land]. The assumption was just that it was all an island. If you look at a modern map of the West Coast of Mexico, the Baja Peninsula is really long.

Author’s note: Edited for space and clarity.

The next journey of this extraordinary 17th-century world map housed at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, is underway. Members, donors, and visitors are helping set the course of this amazing project as conservators preserve the one-of-a-kind map, revealing new discoveries about its production and significance. Learn more at https://40for40.utexas.edu/giving-day/19787/department/29215.