With equal parts clarity and gilded nostalgia, I recall the first time I read the opening line of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Often cited on lists of literature’s great first lines, the unusual configuration of words came tearing off the page. Who begins a story with, “Many years later”?

At age 20—cracking open this strange birthday present from my brother’s impossibly cool then partner—the near mythic first sentence was an electric jolt. The lines had mass and the concomitant gravitational pull from which I could not escape. Some 60 pages later as the first chapter break was revealed, I caught my breath.

At age 20—cracking open this strange birthday present from my brother’s impossibly cool then partner—the near mythic first sentence was an electric jolt. The lines had mass and the concomitant gravitational pull from which I could not escape. Some 60 pages later as the first chapter break was revealed, I caught my breath.

In a word, breathlessness is how I describe the first time reading One Hundred Years of Solitude. Tragedy, absurdity, wisdom, lust unspool from each page. Where the book held me, in other ways, the structure forced me out of rhythm. Wait, what timeline am I on? Which José Arcadio is this? Am I reading about an event yet to come, or one that already happened? And as the apocalyptic ending unfolded with gale force winds, to meet the back cover felt like accomplishment enough. Full digestion of larger themes and efficient symbols was a bridge too far, but for many years to come, my full-throated endorsement of One Hundred Years of Solitude would begin with that first line.

As the churn of a decade moved me from financial services to the arts and humanities, I read the book a second time. I’d been on staff at the Harry Ransom Center for a few months before we acquired the Gabriel García Márquez archive. In celebration, I read One Hundred Years of Solitude with our monthly book club for Ransom Center volunteers.

There are book groups, and then there are book groups populated by literate, curious people who dedicate hundreds of volunteer hours to a humanities research archive, library, and museum. Where I knew what was in this wild terrarium grown by García Márquez, a second reading coupled with our volunteers’ insights allowed me to tilt his creation at new and unexpected angles.

The names, by design, matter, but certainly not to the extent which people get hung up on them. Where it is so easy to be enamored by the tragic, relentless Buendía men, the novel belongs to family matriarch Ursula. The extent to which solitude is inescapable—imprinted on the Buendía DNA—emerged not as a result of the cyclical narratives, but the force moving those gears round and round. Realism is negotiable, and magic is a term employed to apply vague order to a chaotic world. It has rained flowers on countless occasions, and people often see men followed by butterflies. Pretending the world doesn’t offer these realities with the same candor as García Márquez is a conjuring on the reader’s behalf, not some illusion strictly designed by the maestro.

More so than anything, I learned from our volunteers that some people do not like this book. As surprising to me as the ascension of Remedios the Beauty, but a certainty nonetheless, one reader’s classic is another’s tedious slog.

My third reading of One Hundred Years of Solitude has been one transformed by archival material on view in the Ransom Center’s exhibition Gabriel García Márquez: The Making of a Global Writer. Through Gabo’s life beyond the written word, the objects articulating his writer’s journey, untold layers were illuminated around this global literary masterpiece.

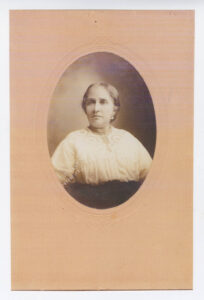

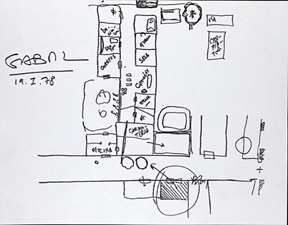

For me, there are numerous standouts among the 300-plus items in the exhibition. A photograph of Gabo’s grandfather, Colonel Nicolas, who fought in the Thousand Days’ War and made small golden fishes in his workshop. Next to it, a photo of his grandmother, Tranquilina, who held the family home together through sheer force of will. A woman who would talk about superstitions and fantastic events in the same prosaic way she’d announce dinner. A hand drawn map of his childhood home, his grandparent’s house in Aracataca, Colombia, with its begonia porch and large chestnut tree. Gabo’s own complicated family tree teased out on axes of legitimate and illegitimate.

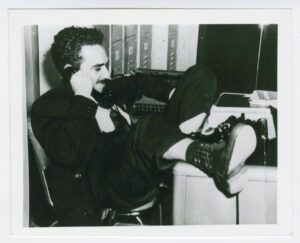

A photograph of Gabo as a young journalist, feet on his desk, phone in hand, all but certain he would someday pen a great work, but who could have no concept of the price of passage. The miles traveled, the financial insecurity, the sacrifices made by others, the false starts before he was finally ready to revisit and complete, “an old project of fantastic stories.” The sum of that furious effort realized in the hand corrected typescript of One Hundred Years of Solitude. Edits offering a peek inside what Gabo called his “carpentry,” the craft of writing, including an excised passage where Gabo and his Barranquilla drinking buddies take shots at Cervantes and Shakespeare. Mountains of correspondence with the global coterie of writers, critics, and friends who provided daily feedback as he poured his entire life, past and present, into this new, ambitious novel. The great novel of solitude written with so much love and support from his friends.

This is my third reading of One Hundred Years of Solitude. Following the breadcrumbs of archival material past Gabo the global icon, past the venerated classic, until at their trailhead is revealed a 23 year old called back to Aracataca to sell his grandparent’s house. When his gauzy nostalgia was met with the truth of the home’s modest structure, the tragedy of the town where his happiest memories lived, a transformation occurred. In this space between embroidered recollection and gut-wrenching reality, his calling as a writer crystallized. Seeds took hold whose blossoms would draw out over the ensuing 15 years. The white house, the outsized characters in his family, the dizzying events of his youth, these things cast a shadow. Gabo understood his story had literary value. His story mattered. And many years later, when he finally told his tale with brick faced authenticity, it felt like nothing short of magic.

Monte Monreal is the Manager of Visitor Experiences at the Harry Ransom Center. He has been with the Center for six years and has a particular fondness for the film and literary manuscript collections.