by DIANA SILVEIRA LEITE and GAILA SIMS

This essay is part of a slow research series, What is Research?

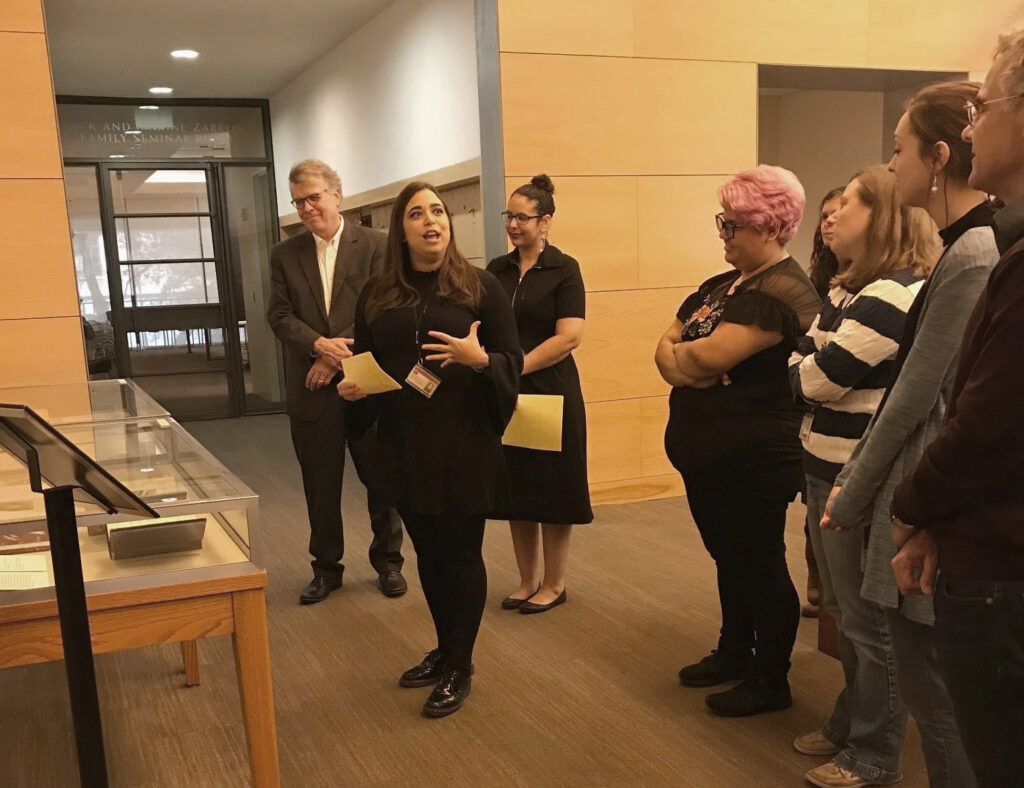

On February 7, 2019 we opened the display of Fugitive Findings: How Artists of Color Survive in the Archives. Presented in two display cases on the second floor in front of the Harry Ransom Center’s Reading and Viewing Room, Fugitive Findings gathered a diversity of materials related to creators of color from within the Ransom Center’s collections.

We positioned a handwritten author biography by Nella Larsen in 1929 above a letter sent in 1956 from author James Baldwin to his editor Phil Vaudrin, juxtaposed with a black-and-white photograph of Baldwin taken in Paris to accompany the publication of his debut novel, Go Tell It On the Mountain. Correspondence between Brazilian novelist Jorge Amado and publisher Alfred Knopf hinted at the enduring friendship between the two literary giants, while a photograph of Kazuo Ishiguro as a baby, surrounded by family samurai heirlooms in Nagasaki in 1955, showed the early life of the Nobel Prize-winning author.

The ostensive goal of the display was to showcase the works of creators of color—with the subtext that we were grappling with an institution that has not always actively procured or assigned prestige to their works. Our covert goal was to signal the lack of diversity in the Center’s historic collecting practices that emphasized the “western canon.” Beginning in 1958, the Center’s initial collection strategy centered on American and English authors from the 20th century, as well as a collection of classics and the theatre from the purchase of the Parsons and the T. E. Hanley Collections.[1] The bulk of the collections still emphasizes late-modern American and European literature. We wanted to reveal the presence of and bring people of color into the Center to get people excited about these gems we had found.

The incomprehensible truth about a place like the Harry Ransom Center is that no single person fully understands what is there. There is infinite room for discovery, but that discovery takes time.

As Graduate Research Assistants (GRAs), we benefited from time and access to the Ransom Center’s massive collections and were thus able to conduct the “slow research” necessary to locate and ultimately highlight creators of color, whose presence in the collections is less obvious. For instance, although much of the Another Country materials by James Baldwin were acquired in the early 1960s, shortly after the novel’s publication, material by and about Baldwin can also be found throughout many other collections. For us, slow research meant immersing ourselves in the archives, learning from those around us how to methodically scan the collections for surprising objects to make new connections.

Given the Ransom Center’s historical collecting practices, the majority of material in the archives comes from white cultural producers, but it is still possible to find objects created by or related to artists of color. A simple keyword search can reveal the presence of these creators within the Finding Aids: the system used by archivists to provide researchers information about individual collections. Beyond these introductory tools, however, the nearly limitless access we enjoyed enabled deep and slow exploration and the delight of discovery.

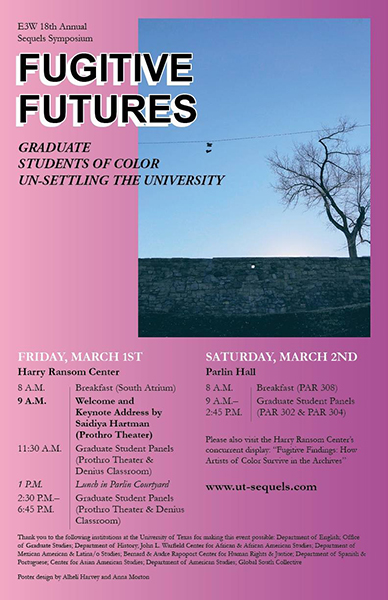

Our display was curated to coincide and dialogue with the Sequels Symposium, “Fugitive Futures: Graduate Students of Color Un-settling the University,” which took place at the Ransom Center’s Prothro Theater and Reading and Viewing Room in 2019, hosted by The University of Texas at Austin’s Ethnic and Third World Literatures concentration and the Global South Collective.

The symposium took up scholars Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s claim that the only possible relationship between “the subversive intellectual” and the modern American university is a criminal one, based on dissident acts and the imperative to “sneak into the university and steal what one can.”[2] The “fugitive” in Fugitive Findings refers to this subversive relationship between scholars of color and cultural institutions in the United States.

The 2019 Sequels Symposium featured keynote speaker Dr. Saidiya Hartman, professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. Hartman, a recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship in 2019, writes about the struggle between scholars committed to studying Black subjectivities and the collecting practices of U.S. archives.

In Hartman’s words, “Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.”[3] Her call to action felt deeply personal to us, as we advocated for a research practice that moved within and against the Ransom Center’s collecting past. In the process of curating Fugitive Findings, we discovered that the essential tool for this kind of revolutionary practice is time.

The process of curating Fugitive Findings taught us three key strategies for creative and careful research. First, that the lateral connections needed to weave an exhibition narrative based on vastly dissimilar subjects—Paul Laurence Dunbar to Jorge Amado to James Baldwin—could only happen slowly. We had to “live” in the archives, and immerse ourselves in the collections for nearly two years. This intimate relationship allowed us to gather a database of lesser known artists we hoped to highlight, making a case for their literary relevance and prestige.

Second, we had to learn to research beyond the Finding Aids and Research and Teaching Guides. The Center provides many research resources, but those systems become increasingly difficult to navigate when the subjects do not have established collections in the archives. For example, in order to find the manuscripts and photographs of Nella Larsen, James Baldwin, Jorge Amado, Harriet de Onís, and João Guimarães Rosa, we delved deeply into the Alfred A. Knopf Inc. Records: a behemoth collection with 635.8 linear feet of material.

Similarly, to locate the words of Nobel laureate writer, Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul, we took a detour through the Mel Gussow Collection. This strategy also reveals that many of the works of artists of color featured in Fugitive Findings were not actively collected, but entered the Ransom Center seemingly surreptitiously, as part of the archives of the white-owned American publishing house (Knopf, Inc.) and a white theatre critic (Gussow). Of the 10 authors featured in the display that we curated, only four are the principal of their own collections: Nobel laureates Gabriel García Márquez and Kazuo Ishiguro, James Baldwin, and prize-winning playwright Adrienne Kennedy.

We had to ‘live’ in the archives, and immerse ourselves in the collections for nearly two years. This intimate relationship allowed us to gather a database of lesser known artists we hoped to highlight, making a case for their literary relevance and prestige.

Our third research strategy depended on our ability to become acquainted with the vast unwritten institutional knowledge at the Center, which was only possible due to our temporary positions as GRAs. This level of immersion requires time for growth, but it also hinges on the researcher’s ability to build relationships with research and curatorial staff—and the Center’s lack of diversity affects this last matter. Nevertheless, some of the most delightful discoveries we made, like V. S. Naipaul’s interview and Nella Larsen’s biography, were aided or inspired by our colleagues.

In Sven Spieker’s “Manifesto for a Slow Archive,” the professor of comparative literature writes, “The slow archive’s element is speed, not space: the (varying) speeds, slowness included, with which we focus on a document and its surroundings, and the difference that makes.”[4]

Our experience curating Fugitive Findings: How Artists of Color Survive in the Archives demonstrates the benefits of this slowness. For two women of color in the early years of our academic careers, limitless time and access to the Ransom Center’s archives was a privilege and a pleasure. But it was in this immersion in the archives that we understood the pain caused by the lack of diversity in the Center’s collections, staff, and visitors. We were able to take a small step toward reckoning with this problem—transforming the privilege of slow research into a right—while working through research and exhibition practices. This process remains a deeply formative experience for both of us.

Throughout this process, we were aware that as Graduate Research Associates on a two-year non-renewable contract, we had limited power to address the deep structural problem of diversity at the Ransom Center, which historically reinforced a hierarchy of cultural prestige founded on white supremacy through its collecting practices and exhibition subjects. But we believed that, through the Fugitive Findings display, we could turn the Harry Ransom Center into the humanities research institution we wished it could be: a place of learning committed to the transformative power of cultural production, capable of using its institutional authority to showcase the incredible literary achievements of creators of color, while also acknowledging that making art requires the privilege of time and financial stability that few Black, indigenous and people of color enjoy.

[1] Decherd Turner, “Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center,” The Handbook of Texas.

[2] Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, “The University and the Undercommons: Seven Theses,” Social Text, vol. 22, no. 2 (2004): 101.

[3] Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019), p. xiii.

[4] Sven Spieker, “Manifesto for a Slow Archive,” ArtMargins, January 31, 2016.