by DANIEL ARBINO

This essay is part of a slow research series, What is Research?

As a librarian at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at The University of Texas at Austin, I have been fortunate to carry values from my personal research journey and apply them to collection development and instruction. On a daily basis, I engage with researchers—faculty, students, scholars, and artists from Latin America and across the globe—whose own research journeys may begin years before they step through our door.

Research begins with passion. A passion to understand and, if we are lucky, to connect with the research in some personal way. I believe that this passion fuels all scholars, writers and artists, even if subconsciously. A passion to approach a work with inquiry, to find a framework, to scour primary and secondary resources to build off of predecessors, and finally, to sit at the computer and give those thoughts a chance to be shared with others. It is a process that can take years from beginning to end. It is a practice of patience, which seems in opposition to passion, but the two are intrinsically connected.

The passion for research often starts with a story, and mine is likely a common story for graduate students. It was one of those literature courses in which a student could write about a topic of interest, so long as it pertained to the course focus on Latin America and women writers and received the professor’s approval. Mine was to be the African diasporic presence in Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies, a canonical work on a family’s plight under the vile dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, who terrorized most of the Dominican Republic from 1930 to 1961.

The cover of the first edition of In the Time of the Butterflies by author Julia Alvarez, whose papers are housed at the Harry Ransom Center. Her novel was first published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill in 1994.

While the book did not explicitly deal with the African diasporic presence in the Dominican Republic, race was abundantly clear, and I walked into the meeting with the professor with 22 textual examples, ready to make my case. Granted, some examples were miniscule, such as the influx of German-manufactured cars that underscored Trujillo’s intimacy with Nazis, despite the fact that he welcomed 100,000 Jews who fled Nazi Germany in order to “whiten” his country. But something was there. After all, this is the Trujillo who wore makeup to lighten his skin. The Trujillo who neglected the fact that his maternal great-grandmother was from Haiti’s mulatto class. The same Trujillo who ordered the brutal killing of approximately 30,000 Haitian workers living in the Dominican Republic in 1937 in what has come to be known as the Parsley Massacre. It seemed to me that there was a need to suss out the implicit commentary that Alvarez was making about Afro-descendants in the Dominican Republic (a commentary that she would further develop in her 2012 non-fiction work A Wedding in Haiti).

My professor disagreed, claiming that there was no presence to speak of in the book. Yielding to her authority, I did not show her the 22 examples, nor did I put up a fight. I simply wrote about something else. This is not meant to place blame on the professor, and in fact, after having a conversation with my mentor, he included In the Time of the Butterflies in his Afro-Caribbean Literature seminar for the next several years. Perhaps in the end, this anecdote was a success story: by using the novel regularly in his syllabus, he validated my idea as worthy of exploration, and now groups of students would be using my research as they developed their own research questions.

Research begins with passion. A passion to understand and, if we are lucky, to connect with the research in some personal way. I believe that this passion fuels all scholars, writers and artists, even if subconsciously. A passion to approach a work with an inquiry, to find a framework, to scour primary and secondary resources to build off of predecessors, and finally, to sit at the computer and give those thoughts a chance to be shared with others.

—DANIEL ARBINO

As for the African diasporic presence in Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies, we might look no further than Fela, the Haitian servant of the family whose knowledge of Vodou allows her to serve as a medium and commune with the dead. Her resiliency is noteworthy, though often overlooked in the novel because her voice is minimized. However, she constantly undermines Trujillo’s power. As a Haitian woman living under the dictatorship, her life is endangered, but she forges ahead. What is more, she maintains her traditional Vodou practices and beliefs in a nation that has attempted to promote Catholicism and stamp out African diasporic religions. Because she passes these beliefs on to the lighter-skinned Mirabal family of the elite class, Fela comes to represent Trujillo’s greatest fear: the “Haitianization” of the Dominican Republic. Fela is not the sole catalyst for the rebellious Mirabal sisters, but her traditional practices give them hope against the despot in the novel, underscoring that the African presence in the text does matter.

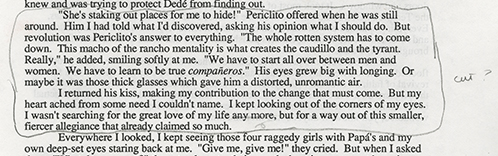

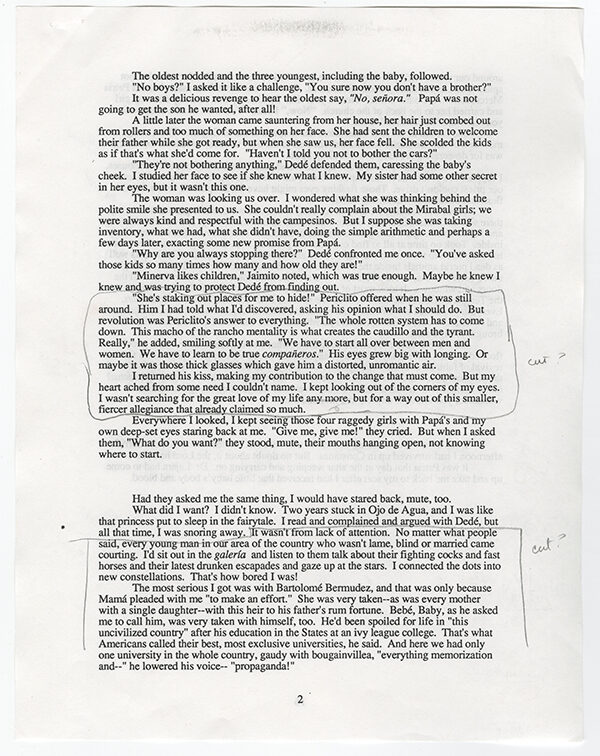

What ultimately appears on a page and what gets scrapped are determined by various factors. In my case, it was hearing that “no.” Although I never wrote about In the Time of the Butterflies, since that fateful day, my passion for research has largely focused on highlighting marginalized voices within Latin American and U.S. Latino literature. From publications on Afro-Uruguayan poetry to Afro-Mexican folktales, from Tejana short stories to Nuevomexicano novels, research has been my vehicle towards advocacy and allyship. Thus, we might conclude that research is also a pathway to growth, personal and societal. Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies seeks to do just that: to tell the story of Trujillo so as to move beyond him. Remarkably, a deleted passage from an early draft highlights Alvarez’s greater vision in which her characters articulate a decolonial desire to start over without repressive patriarchy:

Sometimes the passages that do not make the final cut are just as interesting as those that do. This is why archival preservation is so significant.

At the Benson Latin American Collection, we have many items of value for researchers: over a million volumes and a wealth of original manuscripts, photographs, and various media related to Mexico, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Latina/Latino presence in the United States. Themes vary widely: from the papers of literary giants like Ernesto Cardenal and Miguel Ángel Asturias to those of renowned artists like Liliana Wilson, Carmen Lomas Garza, and Catalina Delgado-Trunk, from Chicano/a do-it-all writer-scholars like Américo Paredes and Alicia Gaspar de Alba to bibliophiles like Genaro García and Joaquín García Icazbalceta, whose collections are foundational to the Benson. The collections of organizations like the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the Mexican Communist Party are equally as tempting. In all cases, we strive to capture those distinctive drafts, annotations, and research files that ultimately make up the final piece that fostered research in the first place.

Having distinguished itself as the premiere Latin American collection in the United States, and perhaps the world, the Benson will celebrate its centennial in 2021. And while we have had 100 years to build that reputation, our official commitment to U.S. Latina/o collections has only existed for half that time. That is why it gives me great pride to see that our most visited collection is that of Gloria Anzaldúa, the queer Chicana feminist. We hope that her archive, as well as those of so many others, usher us into a second century with continued dedication to inclusion.

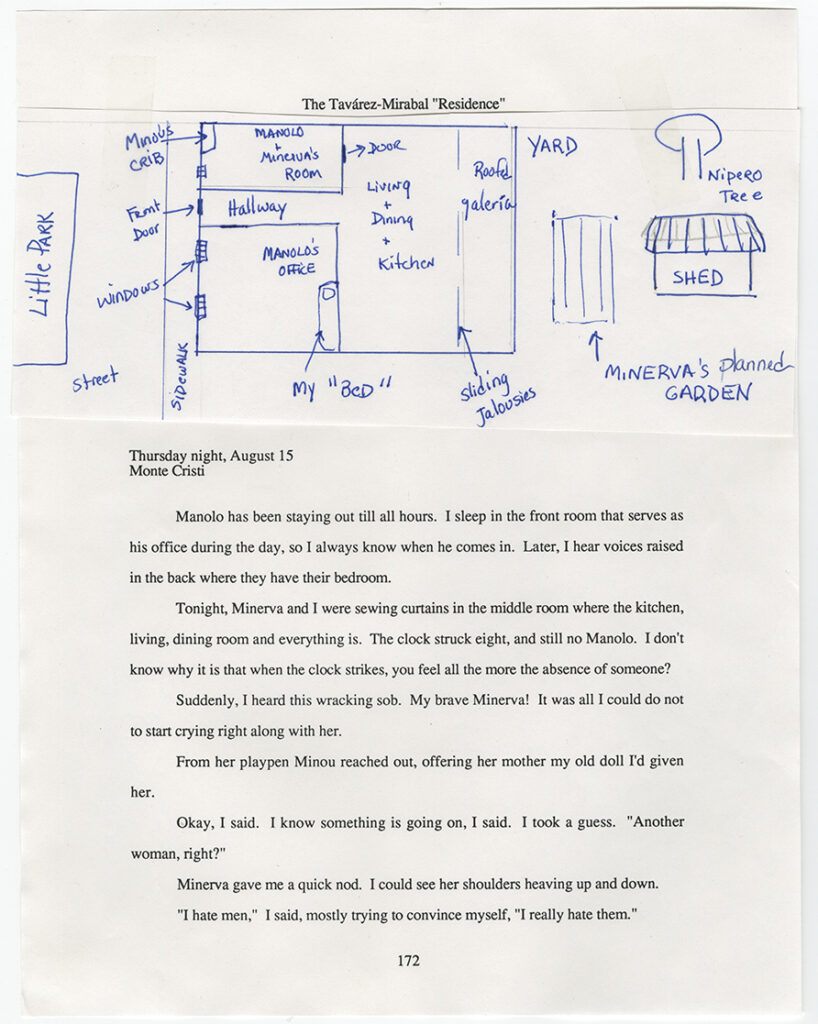

A similar desire arises in me when thinking of the Julia Alvarez Papers, which resides at the Harry Ransom Center, just a short walk from the Benson on the UT campus. One of the advantages of having our collections in close geographic proximity is that researchers can visit both of our collections and make new connections. Alvarez’s papers found a home at the Ransom Center in 2013, so current graduate students can see the original notes and ample evidence of her preliminary research activities for In the Time of the Butterflies and other works. New generations of researchers will ask questions for their courses, theses, dissertations, and other research projects. If archival collections are often thought of as being dominated by white, heterosexual men, what possibilities exist if women’s voices become the most sought after at two of the most important special collections in Texas? What will research be to future generations who can access drafts, journals, notes, and research files of these prominent writers? This is how we push the paradigm forward.