by VANESSA GUIGNERY

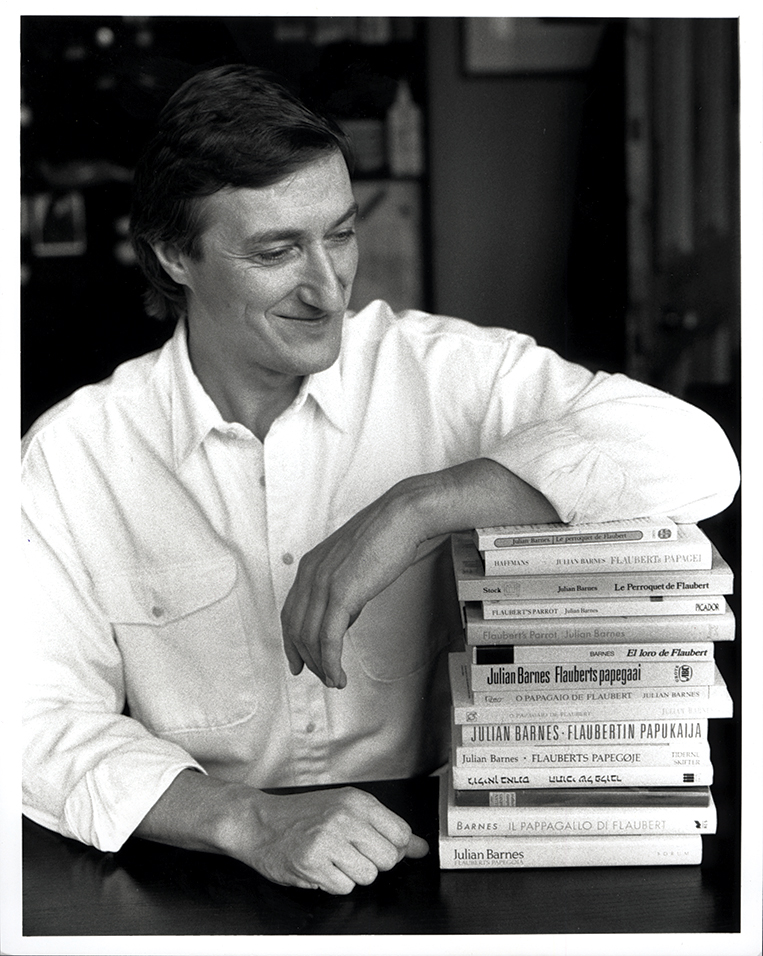

In the fall of 2001, I was in Normandy with author Julian Barnes to take part in an event around his most successful novel, Flaubert’s Parrot (1984), when he told me with a wry smile that I would soon be going to Austin, Texas. As I looked at him quizzically, he explained that he had decided to place his archive at the Harry Ransom Center. At that time, I had completed my doctoral thesis on “Postmodernism and modes of blurring in Julian Barnes’s fiction” at the University of La Sorbonne in Paris and published books and articles of literary analysis of Barnes’s work, but I had never examined a writer’s archive and I had never been to the United States.

After giving it some thought, I applied for a fellowship at the Ransom Center, and in March of 2006, I spent a wonderful month in the reading room going through the first acquisition of Barnes’s papers. I had looked at the catalog online beforehand and had planned to go through each of the 20 boxes that covered Barnes’s published work from his first novel, Metroland (1980), to his 10th, Love, etc. (2000). I was also intrigued by the mention of handwritten notebooks and of an unpublished Literary Guide to Oxford, completed in the 1970s, and by the enticing folder titled “Letters from writers.”

was published in the U.S. in 2020. His papers are housed at the Ransom Center.

The papers relating to the unpublished Guide to Oxford showed how meticulous Barnes was in his methods of research from early on in his career but also how impatient he grew as his publisher kept postponing the project, until Barnes decided to withdraw it altogether. The letters from writers were relatively few because Barnes decided not to include letters from people who are still alive, but I was thrilled to read Philip Larkin’s letter of April 20, 1980, praising Barnes’s novel Metroland and the younger writer’s enthusiastic note on the envelope: “BLOODY MARVELLOUS.” I smiled when reading Kingsley Amis’s postcard sent to Barnes’s wife, Pat Kavanagh, on January 6, 1984: “What a lovely party.… Tell J. sorry I showed boredom over Flaubert’s Parrot—sure it will be great in the book.”

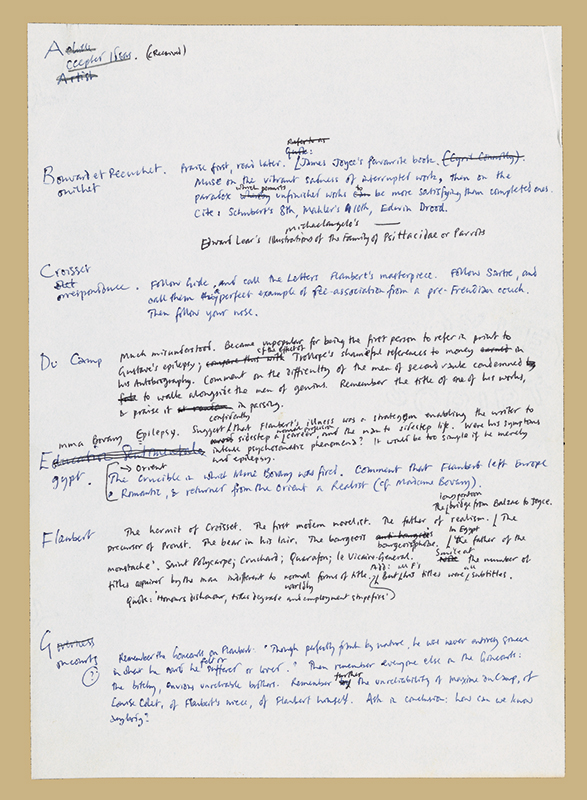

The two handwritten notebooks dating from the late 1970s and early 1980s proved extraordinary as they contain plans and notes for books that were eventually written and published, but also miscellaneous sentences, anecdotes, and ideas for short stories and novels that were never written. Under the title “Novels I want to write” appeared brief indications that announced his second and fourth novels: The “sexual jealousy novel” was to be Before She Met Me (1982), and the “WW2 novel” would become Staring at the Sun (1986). The third description “Praise of younger man/older woman relationship” did not seem to correspond to any published piece when I read it in 2006 but then perfectly fit the plot of The Only Story, Barnes’s 13th novel published in 2018.

It’s odd how, as you proceed towards the final version of the book, your mind/memory seems to wipe out all the false starts you made and blind alleys you went up. So they come as a complete surprise when a French Professor turns them up.

—JULIAN BARNES

In a similar way, I was intrigued by a recurrent sentence in the notebooks—“Let’s get this death thing straight”—which the writer had planned as the first line to his “future novel about Death.” However, the sentence did not appear in any book until his essay/memoir Nothing to Be Frightened Of was published some 30 years later in 2008. I realized how precious archives were in the long term, especially for someone such as Julian Barnes who defines himself as “a slow-burn writer” and once remarked, “Things tend to have to compost down and I store things up without knowing that that’s what I’m doing.”

I would reread these two precious early notebooks several times in the subsequent years to look for clues to future work. Since that first visit, I have returned to the Ransom Center every year to work on the next acquisitions of Barnes’s archive (processed in 2006 and 2015), but also to examine the archives of other contemporary writers, specifically Anita Desai, Zulfikar Ghose, Ian McEwan, and Kazuo Ishiguro.

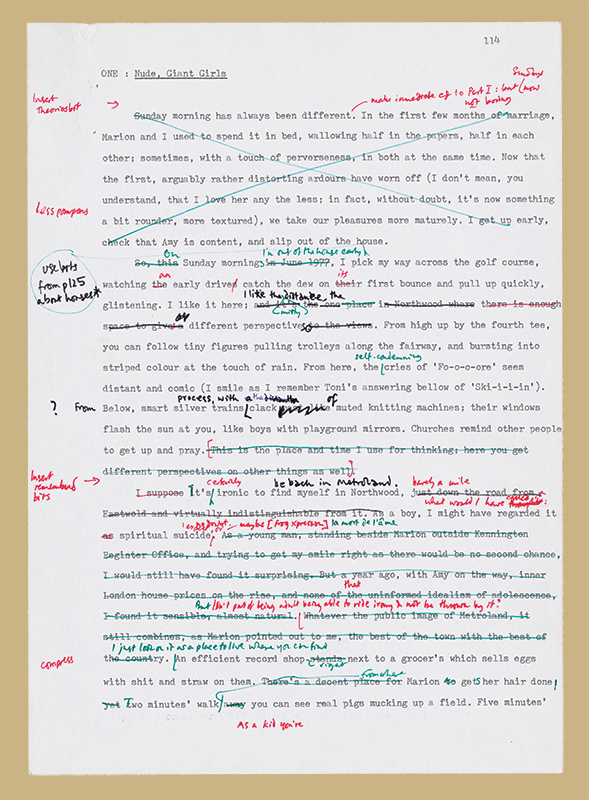

Gradually, I became more efficient and focused in my handling of the material. During my first visit, I did not follow any systematic methodology and took notes only on what I found interesting without any specific project in mind. At that time, cameras were not allowed in the reading room and so one had to choose very carefully which pages to select for photocopies to be made by the Center staff. After accumulating about 500 pages of notes on and off over 10 years, I finally knew that I wanted to write a book about Julian Barnes’s creative process through an analysis of the genesis of his various projects.

I went through the boxes of the three acquisitions yet again, but this time with a different eye and perspective. I knew I could not be exhaustive, but in the genetic dossiers for each of Barnes’s books, I looked for the story that would be interesting to tell.

As Barnes’s writing processes have varied throughout his career, I let myself be inspired by the material contained in the archive rather than developing a method that I would homogeneously apply to each book.

Among the most interesting discoveries was that of the trajectory of Barnes’s Booker Prize–winning novel, The Sense of an Ending (2011), which he had initially conceived as reviving the background and characters of his first novel, Metroland, published 30 years earlier. However, when he moved from handwritten draft to typescript, he made the drastic decision to change all the names and delete all the echoes between the two books so that they now stand (almost) completely apart.

My work in the archive was far from solitary as Julian Barnes always generously and patiently answered my queries or reacted to the emails I sent him while conducting research in the reading room.

One day in January 2017, as I was sharing with him passages he had crossed out in a draft written more than a quarter of a century before and had forgotten about, he wrote to me: “It’s odd how, as you proceed towards the final version of the book, your mind/memory seems to wipe out all the false starts you made and blind alleys you went up. So they come as a complete surprise when a French Professor turns them up.”

Read an excerpt from Guignery’s 2020 book, Julian Barnes from the Margins Exploring the Writer’s Archives.