A day turns into a week into a month, and more. Over the past year, our sense of time has extended into ongoing uncertainty from a global pandemic. For those grounded close to home, if we are lucky, our environments have become circumscribed by thresholds and windows, actual and virtual, sensing global interconnections in the very fragile air that we breathe. Others have been unable to breathe. Challenges this past year, including systemic racial inequities, grow out of long histories. Living in the present, what we call past once had alternative futures, even as our linear narratives timestamp 2020 into 2021.

Over 50 years ago, in 1970, Earth Day was commemorated for the first time. A year before, a massive oil spill off California’s coast of Santa Barbara occurred near natural tar seeps and manmade drilling. While the oil spill did not provoke a collective loss and trauma on scale with a global pandemic, for many the reported devastation awakened a threatened sensibility of a shared home. In the United States, the disaster spurred protections including the Environmental Protection Agency, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act, underscored by earlier influences like Rachel Carson’s watershed book of Silent Spring (1962), prefaced by her “Fable for Tomorrow,” in which humans awoke to a world without birdsong after pesticides dispersed through an ecological web. Such testimonies and consequences did not materialize from thin air, nor from that decade alone. Over centuries, natural histories evolved around “discoveries” of nature and culture, often neglecting timeworn Indigenous knowledges of environmental interdependence.

The Harry Ransom Center was founded in 1957, a few years before the publication of Silent Spring and a few years after Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac (1949) that articulated a similarly entwined “land ethic.”[1] The Ransom Center is relatively young compared to the land that grounds it. On a corner of the sprawling campus of The University of Texas, and within walking distance of the state Capitol, the Center opens to a plaza studded with live oaks, native grasses, drought-resistant perennials, rocks and cacti, surrounded by concrete sidewalks and paved streets. Austin is a city named for a founder of Anglo-American Texas whose statehood dates to 1845, predated by Spanish colonial influences around settled and nomadic Mexican and Indigenous communities.[2] The land under the intersection marked as Guadalupe and W. 21st Street was shaped by the Colorado River and Balcones escarpment that separates the Hill Country from the Blackland Prairies, shaped by larger geological forces on the region: from the westerly canyons of Big Bend, to islands in the Gulf of Mexico, to eastern pineywoods that grow from sandy loam, to the mixed-grass plains of the northerly Panhandle. These are modern names for older places described by other languages. Deep time decenters any Center. Not isolated in time or space, the Ransom Center grows from this surrounding landscape, including local limestone from Hill Country quarried for its walls.

If you visit the Ransom Center for the first time—as I visited a few months before lockdown—you may notice its stalwart limestone building, studded with fossils and softened by etched windows, with interplays of light and shadow. You may go inside to view collection highlights like the Gutenberg Bible or one of the earliest known photographs known as the Niépce Heliograph. By virtue of location, the building is part of the evolving exhibit of The University of Texas, the evolving landscape of Austin. If you pan out from a map, the Center shrinks to a pinpoint, as state and national boundaries dissolve into continental shapes of North and South America. Such sweeps emerge on weather maps, when hurricanes gather in the Gulf or tornadoes surge over the Panhandle. Short-term atmospheric changes shift the weather while climate averages a region’s changing weather over time.

If you are a first-time visitor to Austin—as I also was not long before the pandemic—you may be struck by the region’s sunny weather, amid traffic jams, highrises and building cranes near the dammed Colorado River, called Lady Bird Lake, dotted by paddle-boarders and boaters. You may have come for the city’s hipster splendors: the music scene, SXSW Festival, and mestizo influences where cultures have integrated or segregated or collided. You may notice green parkways along Shoal and Waller Creeks, the green-blue swimhole of Barton Springs, bats on Congress Avenue Bridge, or the flat open sky to the East and undulating hills to the West, where fiery sunsets spread over the growing urban sprawl.

Considering this City in a Garden, Andrew Busch has described its rapid urban development akin to “second nature.” “Austin’s natural landscape was not the untouched virgin land that it was cast as by boosters and environmentalists alike,” as he writes; “instead, technology and political capital turned it into ‘second nature,’ that is, a space that appears pristine but is really a hybrid landscape constructed by humans and reflective of power relations.”[3] Austin’s “second nature” has served as a magnet for population growth and gentrification. Even during a global pandemic and statewide blackout, major companies have relocated to this popular region, cinching an already tight housing supply in a state whose population is projected to double between now and 2050.[4] The pressure on natural resources and ill-equipped energy system was recently tested by a February ice storm that resulted in a statewide blackout. Just as Covid disproportionately affected communities of color, so too did the blackout impact communities across the state. Even the stalwart Ransom Center experienced freezing and flooding. The ubiquitous phrase on maps—YOU ARE HERE—reads differently through diverse perspectives that re-place any place within the wider world.

[click image to see satellite view on Google maps]

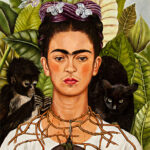

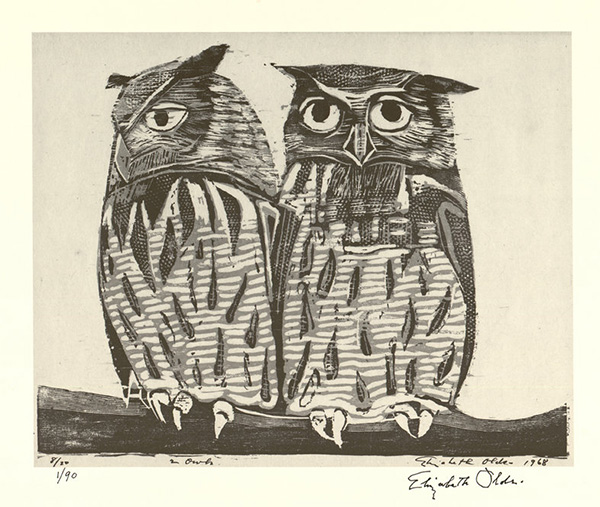

In the Fall of 2019, when I started considering working at the Ransom Center, some of my cursory searches of its collections yielded birds. Years ago I had learned of the Center’s extraordinary range of writers across genres and myriad arts, but I was as interested to learn of less-frequented collections with environmental connections. To some degree, everything in special collections is environmental, based in some form of material culture. Vellum is scraped calfskin. Ground minerals brighten pigments on paintings. Bird feathers frock costumes. Flowers flatten, dried and pressed, between pages. You can find bitumen in early photography; stones behind lithography; wood behind woodcuts. At the Ransom Center, beyond materiality is subject matter: a hummingbird in Frida Kahlo’s self-portrait. Sand dunes in a photograph by Ansel Adams. In the Alfred A. Knopf collection, letters in support of land conservation and national parks. Other relationships form around a first edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, inscribed to Sir J.F.W. Herschel, or Peter Matthiessen’s annotated copy of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.

Apart from individual items are entire environmental-based collections: astronomical, scientific, cartographic.[5] From visual and artistic landscapes to narrative and poetic forms (across pastoral, elegiac, sublime, apocalyptic, speculative, and other lineages), endless interconnections arise. This is the terrain of research: provoking more questions. Online, even before I stepped foot in Austin, I virtually glimpsed the building’s limestone formed from Texas’s ancient seas, exterior lighting replaced a few years ago to curb light pollution and contribute to Texas’s Dark Skies, and other UT repositories that overlapped with Ransom’s collections or that grew up in proximity: from the Lundell Herbarium to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center (in Austin) to McDonald Observatory (in West Texas), among many more.

BIRDWATCHING GALLERY: You can look through the Ransom Center’s collections and find many birds:

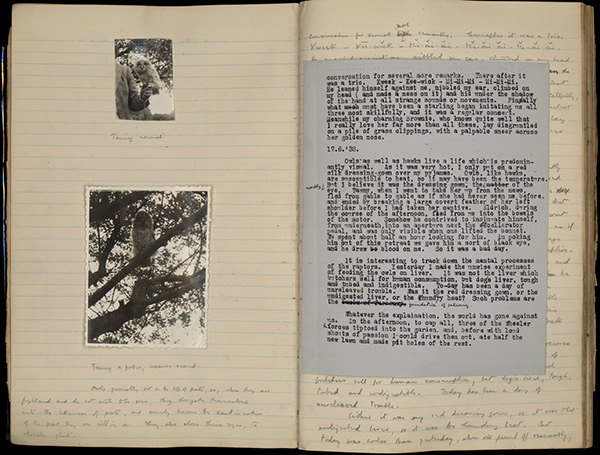

Online access is how many researchers are engaging the Ransom Center during the pandemic (myself included, tethered daily to Austin by telecommute from Washington, DC). Online I can’t smell live oaks or feel baking heat on my skin–both characteristic of the Texas climate—but regardless, I wouldn’t smell or feel such senses in the Center’s Reading and Viewing Room. Collections are climate-controlled to steward the long lives of rare materials and support conservation efforts. Multisensory engagements in library reading rooms are subtle, honing the art of attention: the crackle of turning pages, the smell of dust, even the hush of others listening for dormant stories in hand-held history. Special collections like the Ransom Center depart from museum models that implore a viewer DO NOT TOUCH. Instead, the Center teaches handling with care, so researchers can literally handle history, with all those implications and responsibilities. Perhaps it is a bit like a Stradivarius violin that needs to be played to enliven its sound. But here, the materials re-tune us. Some special collections sponsor open houses likened to “petting zoos,” where visitors can touch vellum and other animal-based materials, calling to mind evolving notions of zoological parks, which over time have shifted their curatorial strategies from cages to conservation-minded habitats.

Over the years, my engagements with museums, libraries, archives, and cultural collections have led me to see them as environmental thresholds, or threshold ecologies. They straddle different material cultures while growing out of diverse locations, communities, professional practices, and wider ecological understandings. Even within an international-serving institution, in an urban environment, a local ecology seeps through to remind us of interconnections beyond human agency (perhaps most striking when it comes in the form of a natural disaster like a hurricane, blackout, or pandemic). As we engage with collections under the same roof, new questions continually arise about their and our interrelations with the planet. Such questions intersect fields and practices around curated spaces that do not fit within walled bounds, yet require other kinds of conservation and collaborative stewardship. National parks and monuments; wildlife refuges; Land art; urban parks and gardens; excavated archaeological sites. Such landscapes, where nature and culture meet, echo with histories and beckon us to listen.

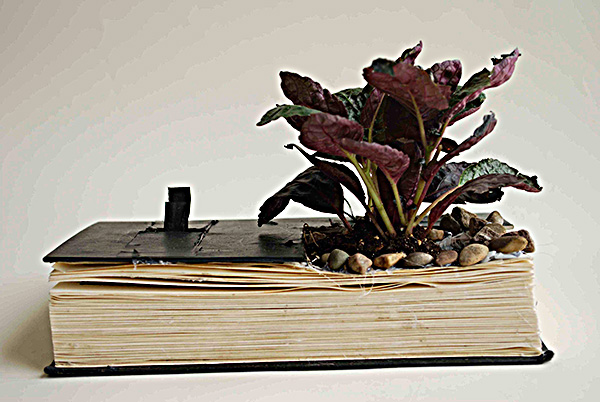

In the humanities, the word “research” conjures visions of libraries as sources for reading. Through books, we learn to read flat surfaces as representations of a three-dimensional world. As my research over years has gravitated to rare libraries, the more that the natural world has pressed back. The materiality of reading and writing grows around pages (so-called leaves), also woven as reeds of papyrus, rooted in clay seals, carved in stone tablets, and scraped as vellum of animal skins. Wormholes dot pages of medieval marginalia twined with vines and wings, painted from pigments of crushed minerals, echoed in digital surrogates embedded with audio clips of birdsongs. From books of ice (a method of conservation) to dirty books (as in, used or well-read), I have tried to read libraries as landscapes (even writing a novel to be read as deforming ecomaterial, so readers planted the book in California, pollinated it with bees and watered it under a growth light in Ohio, wove it in tree branches in Illinois, and in Massachusetts added it to a decomposing bookwall in woods visited by a roaming bear). Beyond artistic license lies an underlying question: Where do libraries meet landscapes? And more pressing: despite overwhelming scientific data of climate change amid widespread denial of its crisis, do we miss something if we overlook the gap between landscapes and libraries, neglecting the potential of this space that might serve as a threshold or bridge?[6]

Earth’s biodiversity is often likened to a library or archive. In special collections, staff regularly stave off minor climate-controlled emergencies–mold outbreaks, pest infestations, plumbing leaks, temperature and humidity fluctuations–extinguishing figurative fires, while the planet heats up and burns. The metaphor of the library stretches only so far, as literary scholar Ursula Heise explains in Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species. Counting species during the current mass extinction, she writes, is comparable to “asking how many books are archived in a library on fire.”[7]. Since humans are responsible for climate change, it is as if “the library is not burning down by accident but because humans use the books to heat their homes.” Correlations between collection conservation and land conservation seem to align as emergencies mount across the globe; the 2019 and 2020 fires through Brazil’s Amazon rainforests eerily echoed blazes that in 2018 engulfed its national museum. Novelist Amitov Ghosh has described compounding global climate events in relation to literary and artistic representations in terms of “The Great Derangement.”[8]

Questions continue to arise. During the pandemic, there has been an understandable rush in libraries to digitize materials: to increase access to collections while libraries are closed, to better accommodate researchers who may never be able to physically travel to collections, to preserve surrogates (especially as libraries literally burn, as sadly happened this week at the University of Cape Town), among other vital considerations. Yet digitizing everything may overlook some long-term considerations–akin to dousing a flame in a hearth while the rest of the house burns down. Digitization efforts currently rely on data centers and computer hardware reliant on fossil fuels with carbon emissions that challenge their environmental sustainability. Thinking about future generations, Penn State archivist Benjamin Goldman asks, “How harshly might these future generations judge an archival profession that preserved documentary heritage using the same resources that created our planet’s crisis in the first place?” [9]

Over the years, my engagements with museums, libraries, archives, and cultural collections have led me to see them as environmental thresholds, or threshold ecologies. They straddle different material cultures while growing out of diverse locations, communities, professional practices, and wider ecological understandings. Even within an international-serving institution, in an urban environment, a local ecology seeps through to remind us of interconnections beyond human agency (perhaps most striking when it comes in the form of a natural disaster like a hurricane, blackout, or pandemic). As we engage with collections under the same roof, new questions continually arise about their and our interrelations with the planet.

—Gretchen E. Henderson

As the Ransom Center looks forward to reopening, like everywhere, much of the future remains uncertain. Even if we appear the same as before, we will not be reopening to a world that was. Many people have asked when operations will return to “normal,” as if a norm ever existed across a diverse and biodiverse world. Whose norm do we privilege? Many resources of the Global North create inequities of the Global South, overusing natural resources and making decisions that jeopardize others’ lives, often through relatively invisible “slow violence.”[10] Our mission is to care for collections in ways that welcome new researchers and encourage diverse interpretations–none of which are isolated but all interconnected, items and contexts, environments and cultures. Any item in a collection was influenced by sources of their materials, by labors of production, and by communities that gave them meaning and accorded values that influenced their use, survival (or neglect), dissemination, and preservation. What and how we collect and protect in the future will be shaped by these evolving understandings.

Gaps in any distinctive collection are as telling as what is present–and this, too, was a critique of the first Earth Day. In 1970, when CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite reported on the first Earth Day, he lauded the cause while questioning what was missing, noting that many advocates were young, White, and from Western countries. Over the decades, more diverse and global voices have been recognized as essential participants in this conversation that ultimately affects everyone. The word ecology grows from Greek roots around “house,” not merely as a structure in isolation, but as a web of interrelationships over time. The founder of Earth Day, Gaylord Nelson (then a senator in Wisconsin), explained this inclusive concept on the eve of its first commemoration: “Ecology is a big science, not a narrow one. It is a big concept, and it is concerned with all the ramifications of all the relationships of all living creatures to each other and their environments.”

As we hope to grow new research around the Ransom Center’s collections, we look forward to future collaborations to ask some of these big questions. Among other unfolding efforts in the Research Division, we have joined with UT’s Humanities Institute (whose 2020-2022 emphasis is “The Humanities in the Environment, the Environment in the Humanities”), Planet Texas (through the Flagship on “Networks for Hazard Preparedness and Response”), the Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Virginia (for a short course on “Writing the Landscape”), and others to think about what and how it means to be a cultural heritage institution practicing in the climate crisis. These collaborative efforts are a form of “slow research” underscored by urgency.

UT has many initiatives already underway—from the Institute for Historical Studies’ 2020-2021 programs around the “Climate in Context,” to the Campus Sustainability Master Plan—to name a few. Similarly, our partner libraries around the country and beyond are investigating environmental intricacies: from the John Carter Brown Library’s initiatives on Indigenous Languages of the Americas and Environmental History; to Dumbarton Oaks’ commitment to Plant Humanities; to the Newberry Library’s Consortium in American Indian and Indigenous Studies and joint fellowship with the American Society for Environmental History; to the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens whose stewardship blends material culture and horticulture; to name a few. All of our institutions grow from successes and failures; since none of us exists in isolation, we look forward to finding new ways to think more collectively.

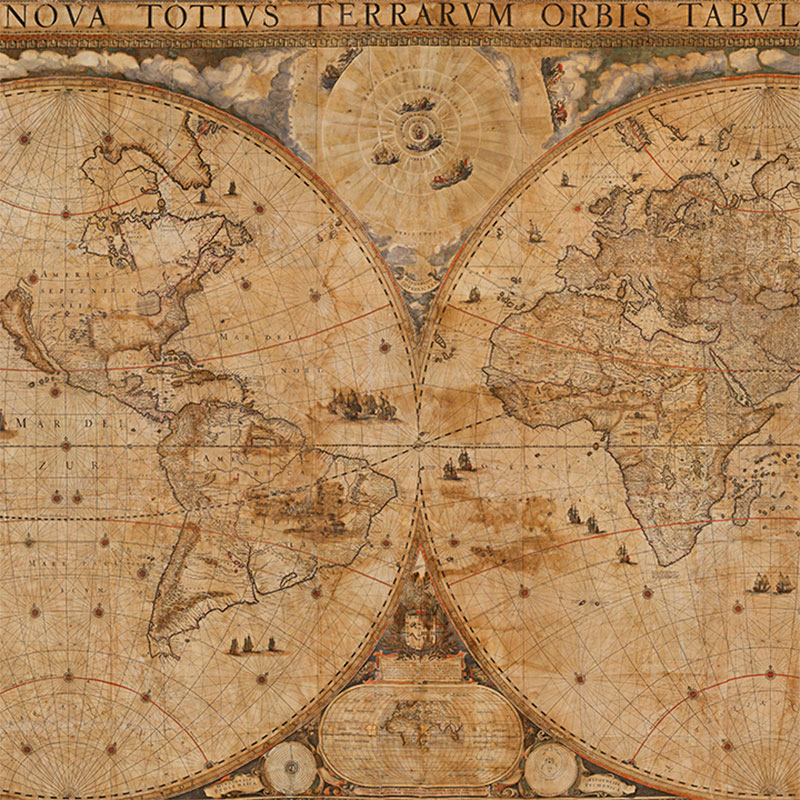

News of the world increasingly feels wrought by crises: across countries and the climate, across higher education down to the humanities. Humanity inspires the humanities, sharing roots with humans and humus, the soil that we all eventually become, and with humility. Many have evoked these shared roots, and history is constantly revealing incomplete aspects of human knowledge. Different representations of the world have arisen over centuries, like the 1648 Blaeu map at the Ransom Center portrays North America with a partial Western coastline and with California is an island. Botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer (Potawatomi) reminds us that more knowledges always lie in our midst, if we look beyond ourselves; as she writes: “In indigenous ways of knowing, other species are recognized not only as persons, but also as teachers who can inspire how we might live. We can learn a new solar economy from plants, medicines from mycelia, and architecture from the ants. By learning from other species, we might even learn humility.”[11] Humans will never know everything, and just as we critique the past, future generations will study the limits of our current understandings. As our narratives expand or limit our perceptions, likewise this essay inhabits contradictions between the lines, borne digitally while aiming to attend to the material world.

“What We Need is Here” wrote Wendell Berry in a poem titled “The Wild Geese” that grew out of his farm in Kentucky. In “Perhaps the World Ends Here,” national poet laureate Joy Harjo (Muscogee) illuminates here around a kitchen table from roots in Oklahoma and beyond. Against the backdrop of an ancient crater lake in Italy, Louise Glück writes, “we are / companions here,” while Denise Levertov encourages, “let’s be here now.”[12] Wherever you are reading this is “here.” To some degree, everywhere is here under a shared atmosphere. An oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara in 1969 is not so different in its wide reach than an oil spill off the coast of Alaska in 1989 or the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Every “here” in some way has an impact on evolving elsewheres, including the Ransom Center, so what we do in Texas affects communities farther afield across places over time. These entanglements lie at the heart of the living planet. On this Earth Day 2021, we invite you to cross a threshold ecology in your midst, to join us in renewing ways to care about our shared planetary home.

Coda:

The Harry Ransom Center has begun a partnership with the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (the former estate of Paul and Rachel Mellon) that is an evolving interconnected rare Library, Garden, and Biocultural Conservation Farm. To learn more about this unfolding partnership, see “Writing the Landscape” (a workshop to be offered in October 2021; scholarships available). To read a bit about Oak Spring during the pandemic, follow some ambles with the author:

Notes

[1] Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1962) and Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989 [1949]).

[2] The land on which the Harry Ransom Center stands previously held tennis courts, a wildflower meadow (that once dramatically caught fire during a dry year), a parking lot, and some of the earliest tree plantings on the campus (including a circle of live oaks referred to as the “twelve apostles,” about half of which remain). Thanks to UT’s Landscape Services (including horticulturist Ty Kasey and landscape architect Lisa Lennon) for sharing the campus’s landscape history and sustainability efforts. Thanks also to UT’s Native American and Indigenous Studies program: “I (We) would like to acknowledge that we are meeting on the Indigenous lands of Turtle Island, the ancestral name for what now is called North America. Moreover, (I) We would like to acknowledge the Alabama-Coushatta, Caddo, Carrizo/Comecrudo, Coahuiltecan, Comanche, Kickapoo, Lipan Apache, Tonkawa and Yslete Del Sur Pueblo, and all the American Indian and Indigenous Peoples and communities who have been or have become a part of these lands and territories in Texas.”

[3] Andrew M. Busch, City in a Garden: Environmental Transformations and Racial Justice in Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), p. 11.

[4] There are many unfolding initiatives through Planet Texas, which reports: “In Texas and elsewhere, the looming realities of rapid population growth and weather intensity mean that the things we rely on to live—water, energy, dependable infrastructure, and an ecosystem to support them—are under unprecedented risk.”

[5] Thanks to reference librarians at the Ransom Center, led by Rick Watson, for answering my questions. Some additional resources on related holdings include the Ransom Center Teaching Guide on Environmental Humanities developed by former Graduate Research Associate, Reid Echols.

[6] Gretchen E. Henderson, “This is Not a Book: Melting Across Bounds,” Journal of Artists’ Books 33 (Spring 2013), pp. 29-33; and Where a Library Meets a Landscape (Upperville, VA: Oak Spring Garden Foundation, 2021, limited print edition chapbook).

[7] Ursula Heise, Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016), pp. 27-28

[8] Amitov Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

[9] Benjamin Matthew Goldman, “It’s Not Easy Being Green(e),” Archival Values: In Honor of Mark A. Greene (Chicago, IL: Society for American Archivists, 2019), p. 274. See also his co-curated exhibit (with Clara Drummond) at Penn State University on the 2020 50th anniversary of Earth Day: “Earth Archives: Stories of Human Impact” and podcast (S2:E2) on “Archivists Against the Climate Crisis” (with Eira Tansey and Nicole Kang Ferraiolo), CLIR Material Memory (11/02/2020).

[10] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

[11] Robin Wall Kimmerer, “Nature Needs a New Pronoun: To Stop the Age of Extinction, Let’s Start by Ditching ‘It,’” Yes Magazine, 03/30/2015; see also Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed, 2013).

[12] Beyond the linked online sources for Wendell Berry and Joy Harjo’s poems, see Louise Gluck, “October,” Averno (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006), p. 13; and Denise Levertov, Selected Poems (New York: New Directions, 2002), p. xv.

![Hummingbird portrayed on Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954), Untitled [Self-portrait with thorn necklace and hummingbird], 1940. Oil on canvas mounted to board. Nickolas Muray Collection of Mexican Art, 66.6 © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.](https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2021/04/earth-day-hrc-2-frida.jpg)