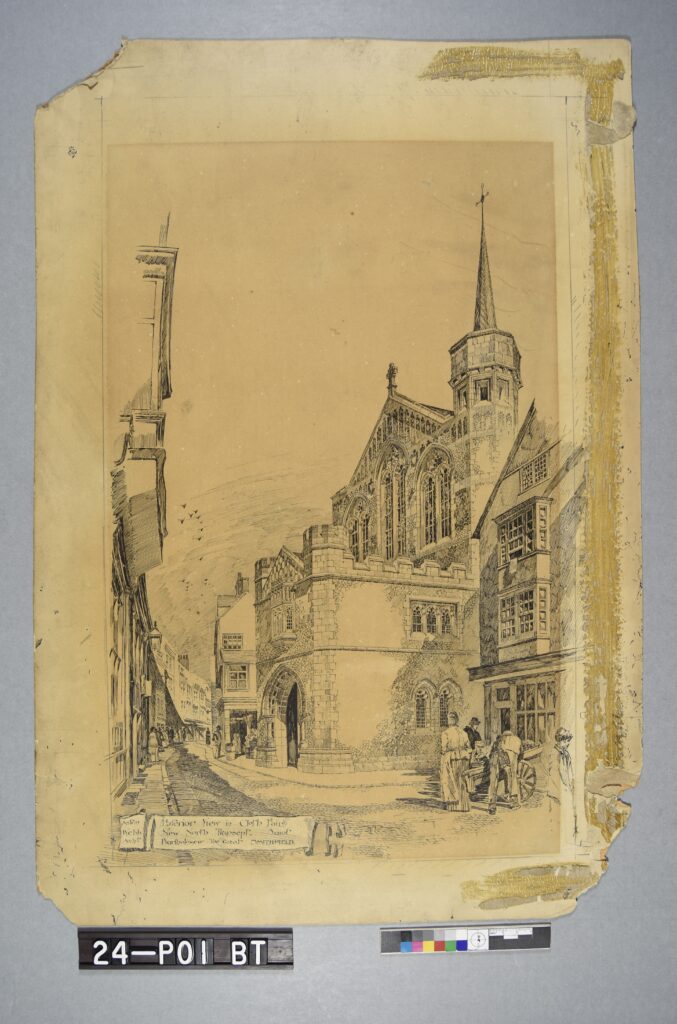

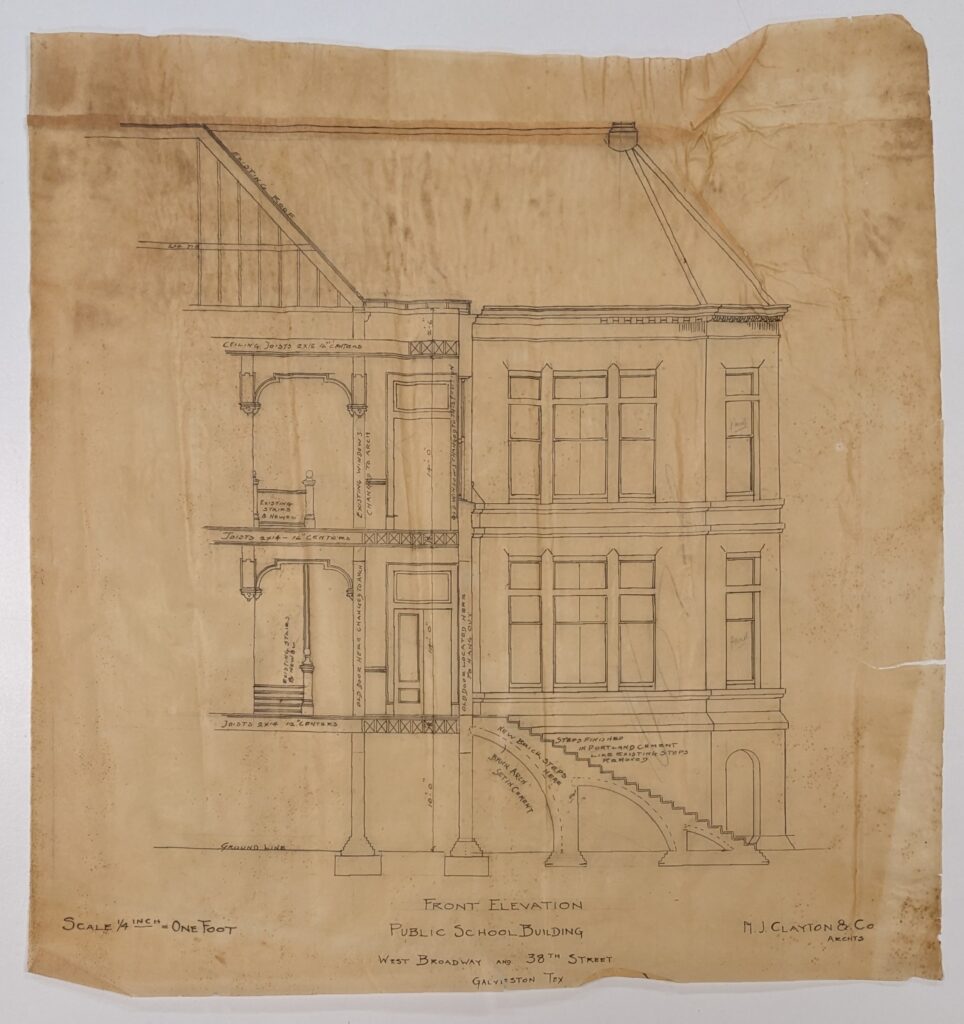

This spring, I conducted conservation treatment on an architectural drawing from the Alexander Architectural Archives. The drawing, by British architect Sir Aston Webb, shows a late-19th-century renovation of the Church of St. Bartholomew the Great. At over 900 years old, St. Bart’s is the oldest surviving church in London!

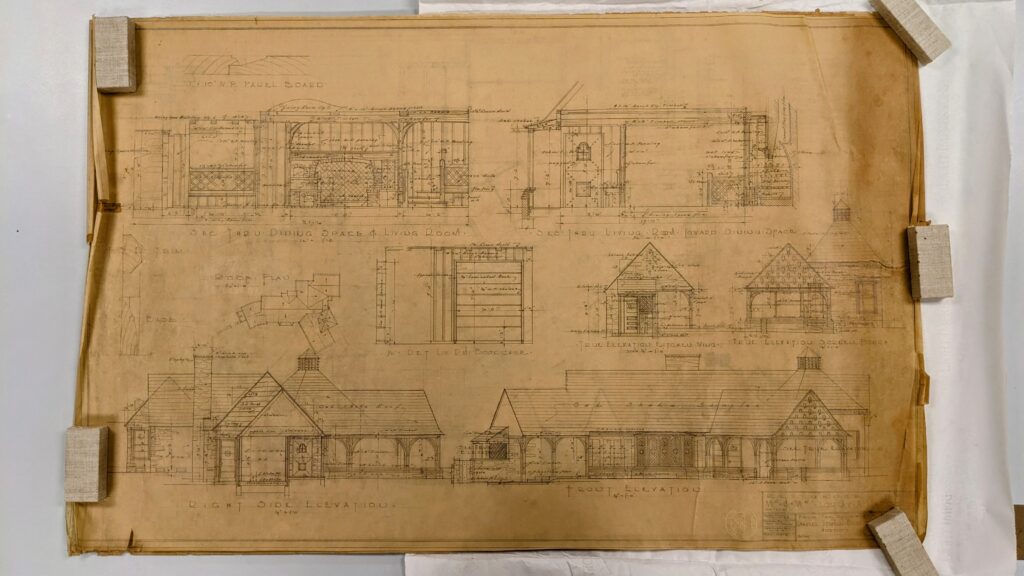

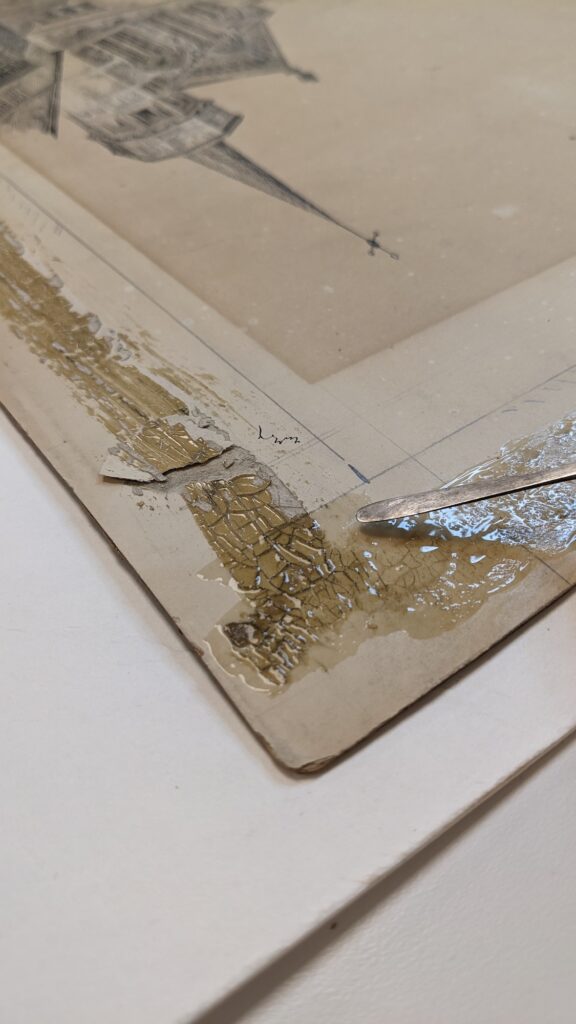

The drawing presented several condition issues. It was covered in a significant layer of grime, likely the result of storage in a sooty London office. The margins displayed a thick layer of brittle, cracked, brown adhesive, likely left behind by a previous display mat. Most significantly, the drawing had been executed on drawing board, a commercially-produced material that becomes acidic with age. Given the board’s deterioration, cracks and losses had occurred, and were likely to worsen with handling. The goals of treatment were to improve stability, access, and aesthetics, and to reduce likelihood of future damage.

First, the drawing was first surface cleaned with brushes and soot sponges, resulting in a notable change in contrast and legibility. Surface cleaning removed acidic components from paper’s surface to slow future pH shifts and to prepare for water-based treatment.

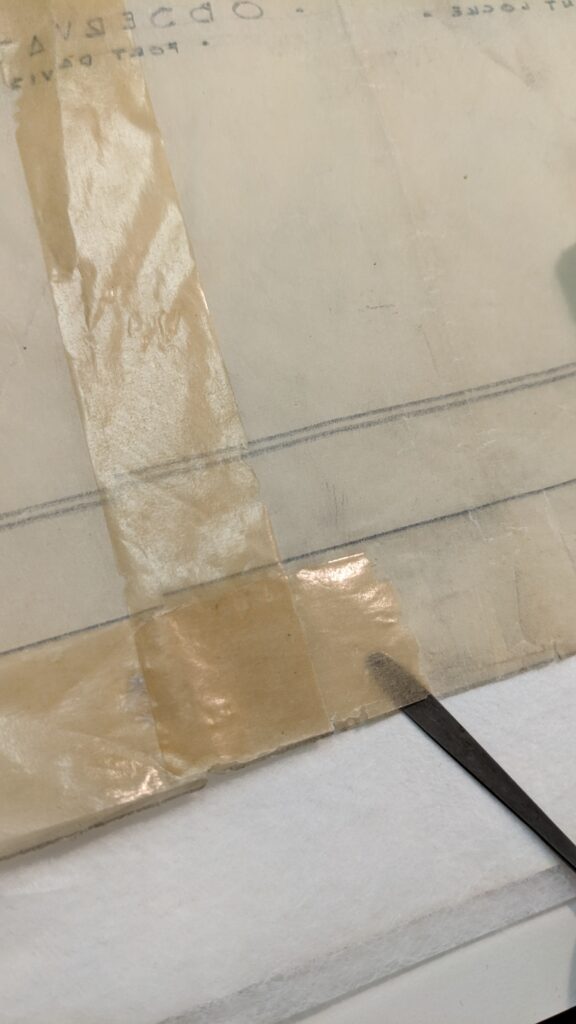

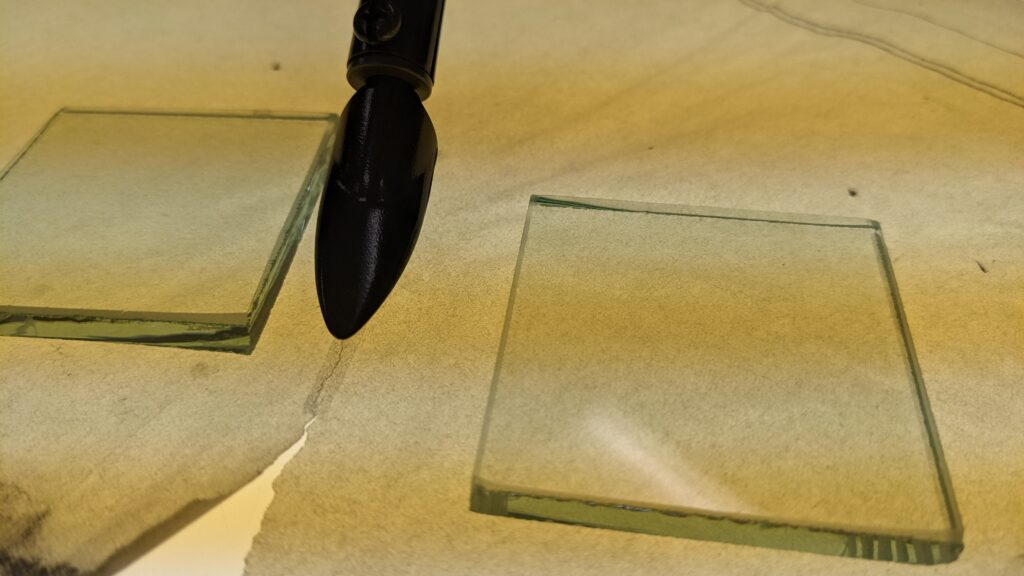

Next, the residual adhesive was softened with successive applications of a methyl cellulose poultice, and mechanically removed with a microspatula. Methyl cellulose is frequently used in conservation as a controlled moisture delivery method. The residual adhesive is glue made from animal hide, so it responds to water without need for more aggresive solvents.

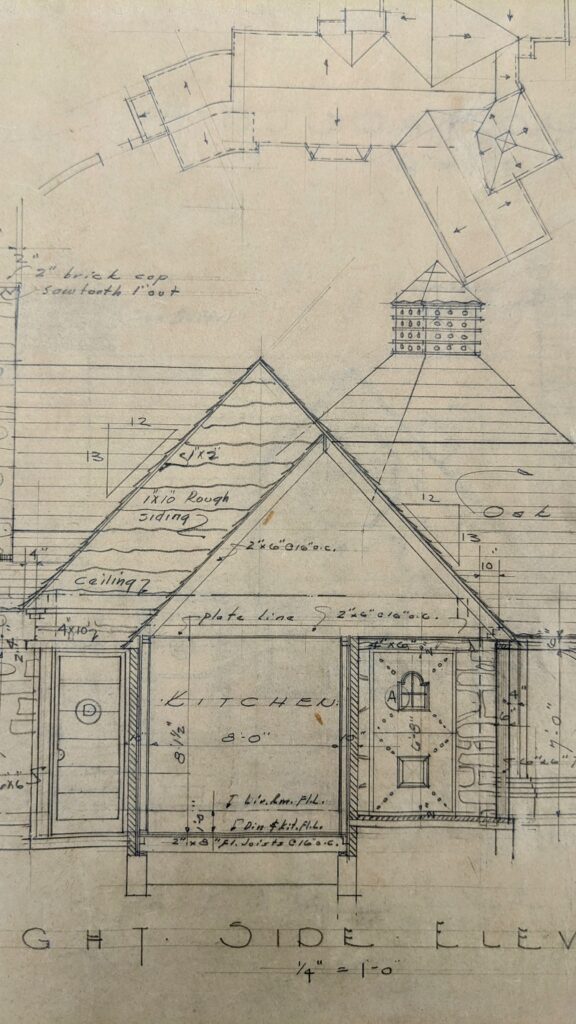

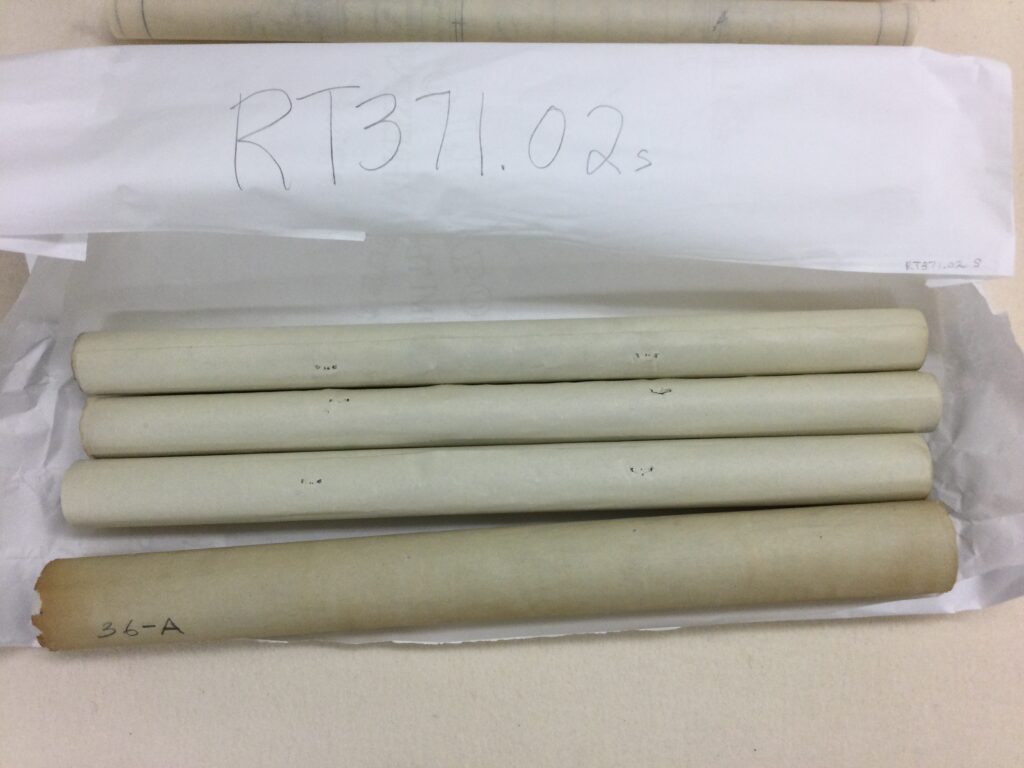

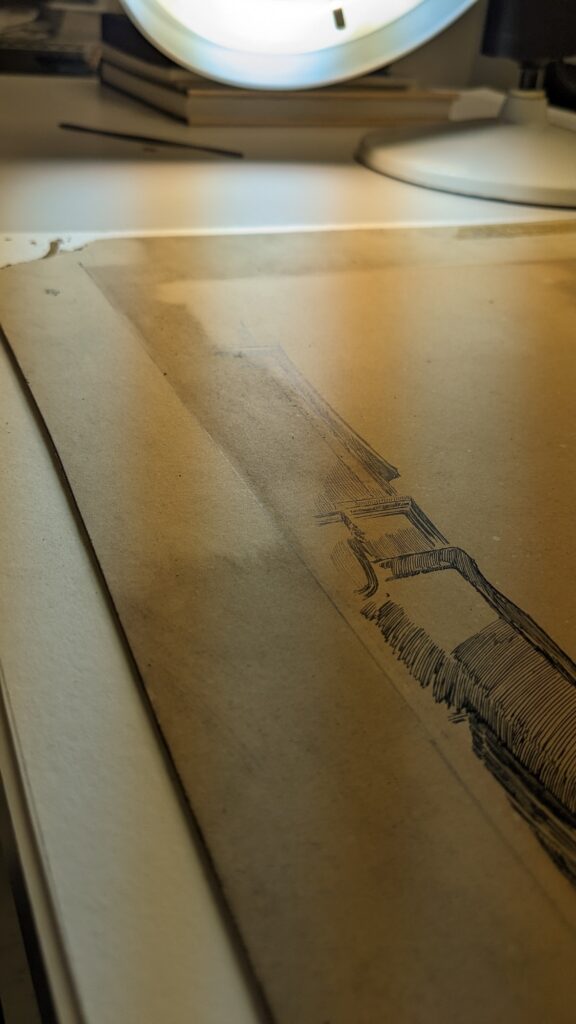

Then, the drawing was removed from its acidic backing board. This process involved using a modified bone tool to split the drawing from its board. Remaining fibers were then pared away with a modified lifting knife while working on a light table. This process represents a major change for the item that requires justification. In this case, removing the backing significantly reduces the risk of future damage, and no significant content was on the back of the drawing.

Last, the drawing was washed on damp blotter to reduce acidity, remove degradation components, and reduce discoloration. A lining of Japanese tissue was then adhered with reversible wheat starch paste to provide ongoing flexibility and stability.

Thanks to the Alexander Architectural Archives for the opportunity to work on this drawing. I hope to visit this building in London someday!