Great news coming out of Vietnam: rhino horn demand is down more than 33% in just one year.

A poll conducted by Neilsen for the Humane Society International (HSI) and the Vietnam Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) found that only 2.6% of people in Vietnam continue to consume rhino horn. This is an incredible decrease of 38% from last year.

THE HSI & CITES CAMPAIGN

News articles announcing the poll results attribute this success to a three-year demand reduction campaign launched by HSI and Cites in 2013. The campaign, which centers on Hanoi, aims at dispelling the misconception that rhino horn can treat diseases such as cancer and rheumatism.

HSI and Cites’ multi-faceted campaign collaborates with various local groups to reach target audiences.

- Women: The campaign partners with the Hanoi Women’s Association to disperse campaign messages to the organization’s 800,000 members.

- Business and academy: HSI and Cites funded workshops at six universities and held a national contest to involve students in designing a demand reduction campaign.

- School-aged children: HSI designed and dispersed an illustrated book, I’m a Little Rhino, with Vietnamese text to 40,000 children.

- General public: Advertisements were strategically placed on billboards, on buses, and at the Hanoi Airport.

HSI claims its campaign is responsible for decreased demand among Vietnamese consumers: “These poll results demonstrate that, even in a relatively short period of time, our demand reduction campaign has succeeded in significantly and dramatically altering public perception and influenced behaviour,” says HSI wildlife director Teresa Telecky.

THE BREAKING THE BRAND CAMPAIGN

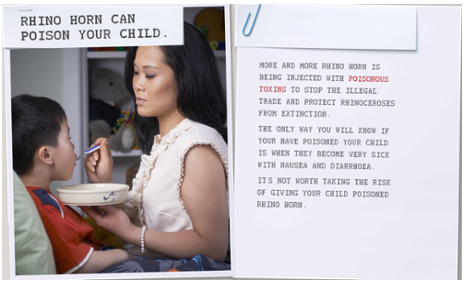

While Vietnamese citizens receive the message from HSI and Cites that rhino horns cannot treat diseases, they are also being bombarded with information that rhino horn consumption has potentially fatal consequences. Lynn Johnson, a businesswoman from Melbourne, Australia started a campaign called Breaking the Brand, which targets advertisements at wealthy Vietnamese consumers.

Instead of the traditional conservation plea, her ads warn consumers that rhino horn powder may contain poison that causes nausea and diarrhea. The hope is that a Vietnamese consumer will think twice before gifting rhino horn to a business partner or feeding it to her own child.

Johnson explains how her method works: “People aren’t worried about the cost of [rhino horn] and they don’t have an affinity for the plight of the rhinos. But we found out they would be worried if the rhino horn had a harmful effect to those they gave it to.”

BUT IS IT TRUE?

Thus far, we have encountered two truths in the above campaigns. The first truth is that rhino horn cannot treat diseases. The second truth is that some rhino horns have been poisoned with the intent to curb poaching and consumption.

Here comes the lie.

Johnson’s efforts to raise money and save the rhinos seem noble. However, we must reconsider upon realizing that her approach is premised on misinformation.

Save the Rhino, a conservation organization, notes that poisoned rhino horn has not been known to cause illness among consumers:

The main reason against the poisoning of rhino horns is that the toxin, which is mixed with the dye in liquid form, does not permeate or spread throughout the high-density fibre of the rhino horn. When studying the distribution of the coloured dye, the researchers found that the dye was only found in the drilling holes and no other part of the horn. This means that the poisoning is ineffective.

The organization warns that poisoning rhino horn neither discourages local poaching nor reduces overseas consumption, and such a tactic could backfire in the long term. It explains that once consumers find out they are not affected by poisoned horns, they may value rhino horn more due to its perceived strength in fighting off toxins. Knowledge that there are poisoned horns in the market may also increase demand for ‘pure’ horns, thereby increasing the incentive for poachers to kill rhinos in greater numbers.

Ethically, we must consider the harm inflicted on populations through intentional misinformation. Some may argue that misinformation for a noble cause is substantially better than misinformation that encourages consumers to believe rhino horn has curative powers. Others may argue that there is no ethical difference between the two.

More importantly, misinformation campaigns risk future distrust.

If Johnson’s campaign backfires and Vietnamese consumers start to distrust public information campaigns, the HSI and Cites campaign and other demand reduction campaigns will be at risk for failure.

PROMOTING TRUTH VS. PROMOTING FEAR

Two campaigns, two approaches. Both claim they are effective in reducing rhino horn demand in Vietnam.

The HSI and Cites campaign is premised on disseminating true and reliable information—that rhino horn is composed of the same material found in hair and fingernails, and has no healing powers. This campaign dispels myths in order to save the rhino.

Breaking the Brand, on the other hand, is premised on disseminating unsubstantiated rumors—that you can kill your own child by using rhino horn. This campaign instills fear in consumers to drive down demand.

When considering the merits of any campaign, it is necessary to consider the short-term and long-term consequences along with ethical concerns. It is not possible at the moment to determine which campaign has a larger effect on consumer behavior. Still, Johnson’s approach has major drawbacks that can compromise the work of other conservation groups, and any success it experiences in the short-term has to be weighed against the potential long-term dangers. On the other hand, rhinos are dying en masse at an alarming rate. If we wait for the long-term to pan out, it may already be too late to save the rhino.

Thank you for sharing with us, I believe this website genuinely stands out : D.