My last post addressed ways in which the Chinese government has attempted to protect its domestic elephant population. Most of the efforts have been aimed at enhancing park conditions and patrols, as well as providing support to farmers affected by elephant attacks (including relocation and economic aid). Promoting elephant protection and awareness through public campaigns—mainly targeting tourists—has also been part of the strategy. The post ended questioning whether the strategies used towards China’s elephants could be used to help protect Africa’s elephants from Chinese consumption. The answer could be “yes”, but it will take time.

In the protection of Chinese elephants, a key element to its success could be identified: a high degree of governmental will and involvement. Local government authorities in the Yunnan province designated large amounts of funding to address the issue, as mentioned above, and worked with environmental authorities and organizations. Efforts were also made to prosecute poaching crimes, reducing the number of killed animals in the region. Authorities recognized elephants as charismatic animals that deserved attention, partly due to their “marketing” value in the tourism sector. Both local governments and the public considered the specie to be special and in need of protection—within China.

Unfortunately, this element is hard to find today at a national level with respect to elephants being poached abroad. So far, top governmental authorities have sent mixed signals about their commitment to wildlife protection in general. The Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife (effective as of March 1989) appears to be under review, possibly a consequence of domestic and international pressures for increased attention to the problem. In a similar vein, the use of shark fins in official banquets has been banned, plunging the sale of shark fin soup and symbolizing the state’s resolve to boost its reputation as austere and environmentally conscious.

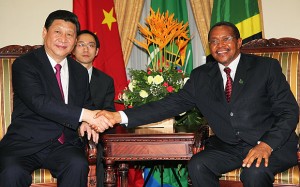

But efforts against the use of rhino horns, tiger bones and (legally and illegally) imported elephant ivory have not been pursued to the same extent. On the contrary, a recent scandal around the smuggling of elephant ivory from Tanzania inside Chinese diplomatic suitcases aboard President Xi Jinping’s official airplane, highlight the complicity of top governmental authorities with illicit trade. A report by the Environmental Investigation Agency also states that staff members of the Chinese Embassy in Tanzania are major buyers of illegal ivory.

An argument sometimes used by Chinese wildlife officials (in this case for the use of tiger bone) is that countries have the right to use their “domestic natural resources” as they see fit—reflecting the long held belief of man’s rule and right over natural resources. It is perhaps the internalization of this belief (along with the high profits associated with illegal trade) what has made some Chinese officials become part of ivory smuggling. If authorities at different governmental levels are not committed to global wildlife protection, however, efforts by conservation groups might prove futile. As the successful case of Chinese elephant protection shows, governmental involvement in the cause—here mainly through funding and enforcement—can certainly make a difference. Perhaps public awareness campaign creators should find ways to target their message to governmental officials, given the centrality of Chinese authorities in the buying and selling of African ivory and their relevance in the success (or failure) of conservation efforts. In any case, it will take time before notions of conservation replace those of profit/ national sovereignty over nature.

Leave a Reply