In Cameron Lagrone’s January post, she argues that “for an awareness campaign to be truly effective [it] must operate in the language of the target country, appeal to the culture of that country and use culturally relevant methods to reach the public.” Inspired by her words, I decided to explore (seemingly) successful public awareness campaigns in China, but in other non-wildlife related topics. My objective was to corroborate whether in fact the elements of language, culture and relevant methods were present in effective campaigns. Most of these campaigns were funded by non-Chinese organizations, or at least received international support and advice. An analysis of these campaigns will be useful in understanding what are the most effective ways to reach Chinese consumers of wildlife products in order to influence their consumption patterns.

This campaign was aimed at generating public conversation about LGBT issues and to encourage people to “come out of the closet.” In China, LGBT topics continue to be largely taboo. So with support from the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center, organizers officially launched the campaign this past Valentine’s Day. It included ads in social media sites in China (namely Sina Weibo), in which LGBT couples appeared in casual locations—a living room, a kitchen, a backyard—hugging and/or kissing. The photographs were accompanied by text underscoring how being homosexual or heterosexual is not a choice. The campaign also invited members of the LGBT community to upload their own pictures kissing their partners on to the campaign’s website…however there are only two pictures uploaded so far. Despite the (perhaps) shyness of participants, this campaign attracted media attention.

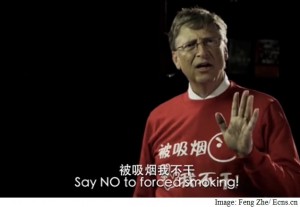

As its name suggests, the objective of this campaign funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was to empower non-smokers in China. Its central element was a music video—starred by Bill Gates himself—that was circled in Chinese video streaming websites. It hired over 1,000 volunteers, including Chinese celebrities like Feng Zhe, Olympian gymnast. Through social networking sites like Sina Weibo and Baidu, the public was invited to share their anti-smoking stories by creating videos themselves, uploading them and voting for the best video. This campaign was particularly timely, since during the same month, the Chinese government passed an important anti-smoking law. Although I tried accessing the music video, I could only find reviews of it.

Organized by the Bethel organization for blind children, the “Love is Blind, Look with your Heart” campaign was launched last fall in Beijing during the International White Cane Safety Day. Through this campaign, organizers wanted to promote the abilities of blind children, calling for the public to believe in their talents and skills. For that reason, they created a music video in which blind Chinese children sing, dance, read and paint. The video was directed by Chinese independent filmmaker Jennifer Liao, with support from editors and producers in the UK, France, US, Switzerland and the Netherlands. The video was presented to members of the business and NGO community, but it was also shared through social media.

Created by Manhattan-based marketing firm Ogilvy, “Words can be Weapons” was released last summer to combat rising numbers of juvenile court hearings in China and to raise awareness of the psychological effects of verbal abuse. It revolved around the campaign’s website, which was created by the Chinese artist Yong Xie. He creatively drew and animated Chinese insult phrases as if they were steel weapons, linking them to videos of real life cases of abuse that led young people to commit crimes. This webpage was complemented with a public exposition at a shopping center in Shenyang in which the public was able to interact with these steel characters, as well as with touch screens that showed the above-mentioned videos. They also reached to younger audiences through popular social media sites We Chat and Sina Weibo, providing the telephone number of a helpline (ran by the Center for Psychological Research in Shenyang), which received more than 300 calls in only two weeks.

Conclusion

Despite the wide range of topics these campaigns addressed, it is interesting to note how they shared similar ways of approaching their Chinese audience. As Cameron identified, the language used was always Chinese (except for Bill Gates, who I guess has not had the time to learn Mandarin), local celebrities were involved in many cases and social media was a key element. Campaigns like Bethel’s and Ogilvy’s appealed to the hearts of their audiences by presenting real life cases of society members who needed their help. What was most surprising was how these projects invited audiences to be part of the campaign themselves, turning the campaign into an interactive process in which the audience also had a voice. Although the assessment of how effective these campaigns have actually been is yet to be conducted (if it ever is), they do work as reference for wildlife conservation and demand reduction efforts. Could there be ways in which Chinese audiences could interact with a demand reduction campaign? Would such interaction increase the likelihood of audiences modifying their behavior? How should the message be framed and who would be the targeted audience?

Leave a Reply