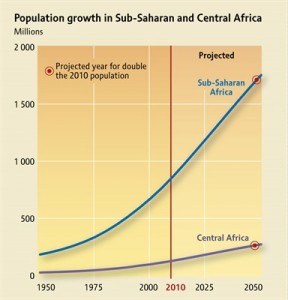

Human-wildlife conflict, at its core, is essentially a struggle over land use. Cattle grazing, agriculture, and other profitable land uses are attractive alternatives to preserving land for the conservation of species in many range countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa where fertility rates are among the highest in the world. By some estimates, the population in Sub-Saharan Africa will more than double in the next 35 years, increasing from 926 million people to 2.2 billion people by 2050.

Therefore mitigating human-wildlife conflict is imperative for many reasons, not the least of which is preserving species’ habitat so that both the wildlife itself and the ecotourism industry can thrive (you can read more on why this industry is vital to developing countries in others posts including here). But this is a challenging task for one very specific reason: community buy-in is necessary in order to mitigate human-wildlife conflict and conserve species, but the communities that you need to actively support species conservation are the same communities that are creating the conflict in the first place. In addition, a solution to human-wildlife conflict that works in one community may be completely ineffective in another community.

So how can human-wildlife conflict be alleviated? Community development and job creation efforts can be a way of mitigating this conflict, however these projects must be carefully thought out before any action is taken.

In Tanzania, we spoke to an employee at the PAMS Foundation, who wished to remain anonymous. This interviewee diagnosed several common problems with efforts to curb human-wildlife conflict. One such problem was a lack of proper community buy-in and involvement. But another was that there is no real way to measure the “success” of these projects to mitigate human-wildlife conflict. Instead “success” is often measured only in dollars spent and projects completed. Yet in reality, there is no real, tangible success on the ground, and the conflict continues. In many instances the plan of action for mitigating human-wildlife conflict may seem brilliant, yet in reality things do not always work out as they are planned. So what should be done?

The financing institution, whether it is USAID or another, must take responsibility for the use of the funds that they are providing. Follow-up investigations could be done in order to ensure proper use of funds and the success of the project. The budget of a project should not only include the cost of completing said project, but the cost of a follow-up investigation as well. These investigations would typically occur between six months and one year after the project’s completion, although exceptions can be made when appropriate. Adaptive management strategies could also be employed in order to fix problems with projects while they are still underway. These simple strategies can do a lot to improve the effectiveness of projects to mitigate human-wildlife conflict in range countries.

Furthermore, aid should be given to proven, well-established NGOs and other not-for-profit organizations working in the field. While some may think that this currently the protocol for the USG, unfortunately this is not always the case. Monetary aid should not be dispensed without thorough investigation into both the organization’s history of success in mitigating human-wildlife conflict and their plan for spending the funds in question. Less money should be given directly to the national governments of the range countries in question, for there is often great potential for it to fall into the wrong hands or be used for unintended and less beneficial purposes. However there are both pros and cons to this policy option.

Pros: This financing and project management strategy would increase the overall success and effectiveness of projects meant to mitigate human-wildlife conflict in range countries. Thus, the value of each dollar spent in-country would also increase. Eventually, foreign aid would be directed toward only the most effective and promising solutions. Finally, with more effectively targeted aid, human-wildlife conflict in range countries would decrease over time. This would allow species conservation to flourish, while still providing enough space for humanity to live comfortably.

This policy option would fulfill several objectives of the Plan including supporting community-based wildlife conservation, building partnerships to reduce domestic demand, and promoting effective international partnerships.

Cons: These methods could possibly be a hard sell to the very organizations in which they would need to be implemented. Large international financing organizations are often tied-up in bureaucracy, with strict protocol for their operations. This kind of change, especially the adaptive management piece, would most likely need to be implemented through a top-down approach. This could be difficult unless the large stakeholders in the organizations are on-board, which would mean convincing them of the necessary change.

Leave a Reply