By Mandy Ryan

Chances are, you or someone you know has or has had a disability at some point in their lives. Chances are, you know someone who has a disability that you don’t know about. This invisibility is one of the reasons the A in IDEA (inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility) can be tricky to tackle. With this in mind, we want to give a shout out to all of those honoring Disability Pride Day with us and give some background for those who may not know why we’re celebrating.

What is Disability Pride Day?

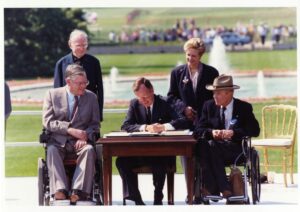

Disability Pride Day is a celebration of the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) into law on July 26th, 1990. The ADA ushered in a new era for the disability community and implemented one of the first civil rights laws prohibiting discrimination against disabilities in the world. It also requires that employers, businesses, and public entities provide accessibility and reasonable accommodations to ensure that the disability community can have equal rights and opportunities as everyone else. Initially held in Boston, Disability Pride celebrations spread to Chicago and then to New York City, where Mayor Bill de Blasio declared July as Disability Pride Month and announced the first annual NYC Disability Pride Parade. Today, Disability Pride is hosted in major cities across the US and has even become an internationally recognized celebration. Spearheaded by disabled influencers, Tiktok reported that the hashtag #DisabilityPride has reached over 236.6M views by the end of July.

Photo of President George Bush signing into law the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 on the South Lawn of the White House. L to R, sitting: Evan Kemp, Chairman, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Justin Dart, Chairman, President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities. L to R, standing: Rev. Harold Wilke and Swift Parrino, Chairperson, National Council on Disability, 07/26/1990. Photo courtesy of the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum/NARA.

Why is Disability Pride important?

Disability Pride plays a key role in breaking down stereotypes and challenging what it means to have a disability through visibility and awareness. It allows the disability community to gather together to celebrate their uniqueness and recognize that they are a natural and beautiful part of human diversity in which people living with disabilities can take pride. Additionally, this visibility plays an important part in challenging systemic ableism and generating momentum for advocacy. According to a 2018 report by the CDC, “one in 4 U.S. adults – 61 million Americans – have a disability that impacts major life events.” In the LIS profession, librarians with disabilities are estimated to make up 3.7% of United States librarianship. However, visibility for librarians with disabilities is still a major issue. There have been few studies that have examined librarians with disabilities and even fewer professional organizations in this field that have disability-related groups or programs. A recent survey of academic librarians with disabilities found that this lack of awareness and cultural stereotyping impacted their workplace experience, most commonly through a reluctance to disclose their disability or a reluctance to request accommodations at work.

What can allies do?

Diversify the voices in your life by engaging with and supporting disability community members.

- The New York Public Library created this list of recommended books in celebration of Disability Pride Month.

- Love podcasts? Try The Accessible Stall and Disability Visibility, the latter of which is hosted by Alice Wong who has a book by the same name on the NYPL booklist. If you’d like to listen to something with a university-focus, Colorado State University’s Student Disability Center hosts the podcast Disability Dialogue, featuring voices and experiences from students and faculty.

- Follow accounts on Instagram and Twitter that promote diverse perspectives, such as Disability Together (@disabilitytogether) and Diversability (@diversability).

- Support disabled-owned bookstores, including Spurgin Stationers in Marfa (they ship!). Prefer audio books? Libro.fm put together this list of disabled-owned bookstores that have audio book storefronts.

Take time to educate yourself on ableism and where it exists.

- It’s important to understand the systemic ableism that exists in our society so that we can recognize issues and advocate for safe and accessible spaces for all. Follow these local Austin organizations to learn more about what’s happening with disability rights in our city:

Learn more about the history of Disability Rights and Disabilities Studies.

- Check out UTL’s Disability Studies LibGuide for more information, recommended readings, and additional resources.

- Read Elizabeth Gerberich’s blog post, Disability Studies: An Introduction, on the DAC website.

- Explore UT Arlington’s Texas Disability History Collection, featuring one of the largest online exhibits of archival material related to the disability rights movement in the state.

Support campus initiatives that help our disability community.

- Did you know that the Texas Center for Disabilities Studies and the Disability Advocacy Student Coalition started an initiative for a UT-Austin Disability Cultural Center? Follow their progress and learn about other disabilities-minded events on campus through their website.

- UT’s Division of Diversity and Community Engagement routinely puts out resources for the campus disability community, including COVID-19 related resources.

- Housed under the DDCE department, Services for Students with Disabilities releases a monthly newsletter highlighting work and events happening around campus for students and faculty.

Get involved with disability-related organizations in the LIS profession.

- Society of American Archivists Accessibility and Disability Section is working to create an inclusive space for archivists with disabilities and allies.

- The book, Beyond Accommodation: Creating an Inclusive Workplace for Disabled Library Workers, by Jessica Schomberg and Wendy Highby, applies critical disability theory to the library profession and discusses practical ways to improve our workplace.

- #CripLib is a hashtag used when discussing the intersection of disability and libraries, predominantly by library and archives workers with disabilities. It has expanded into a monthly chat hosted on Discord that features topics related to accessibility in the library profession. Follow the hashtag on Twitter or visit the website to get an invitation to the chat.

- Support the newly launched Disability Archives Lab, directed by Gracen Brilmyer, Assistant Professor at the School of Information Studies at McGill University, which hosts “multi-disciplinary projects and research initiatives that center the politics of disability, how disabled people are affected by archival representation, and how to imagine archival futures that are centered around disabled desires.”

Terminology and language used in this post was researched and selected using the National Center for Disability and Journalism’s Disability Language Style Guide.

Further Readings:

- Katz, Linda S. Reference Services for the Unserved / by Linda S Katz. First edition. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis, an imprint of Routledge, 2019. Print.

- Oud, Joanne. “Academic Librarians with Disabilities: Job Perceptions and Factors Influencing Positive Workplace Experiences.” Partnership 13.1 (2018): 1–30. Web.

- Wong, Alice. Disability Visibility : First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century / Edited by Alice Wong. New York: Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2020. Print.

- Zames, Frieda, and Doris Fleischer. The Disability Rights Movement: From Charity to Confrontation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011. Print.