The complement system is an interdigitated array of three pathways that act as part of the innate immune response to protect against extracellular pathogens. Dysregulation or hyperactivation of the complement system is associated with various inflammatory and autoimmune conditions (Karpman et al., 2015; Ballanti et al., 2013; Jensen, 1967). The classical complement pathway consists of the hexameric protein C1q which, in combination with the serine proteases C1r and C1s, binds to antibody (IgM or IgG) attached to the surface of a pathogen. This interaction activates C1q to cleave C1r/s, initiating a cascade that results in the deposition of the protein C3b on the pathogen surface, marking it for uptake by phagocytic cells. The alternative pathway is initiated spontaneously in the blood by the constitutive cleavage of the protein C3 to C3(H2O), which leads to subsequent cleavage events resulting in the deposition of C3b on pathogen surfaces. Finally, the lectin pathway utilizes many of the same protein components as the classical pathway, but is initiated when proteins called mannose-binding lectins (MBLs) or ficolins recognize and bind carbohydrates on the surfaces of pathogens, thereby activating the serine proteases MASP-1, -2, and -3; likewise, the lectin pathway results in deposition of C3b (Noris, Remuzzi, 2013).

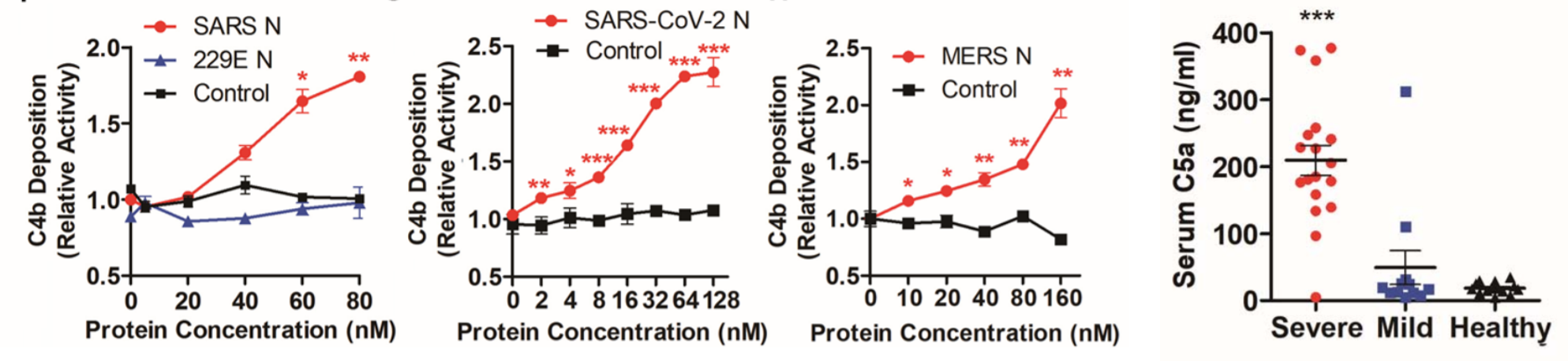

Gao et al. carried out a study to determine the effect that SARS-CoV-2 has on complement activation. Purified MASP-2 was tagged with a molecule called Flag that allows it to be observed in various assays. MASP-2-Flag was then incubated in the 293T cell line with MBL and mannan, the cell-surface molecule to which MBL binds for activation, with or without the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein, and the cells were assayed for MASP-2 cleavage. The researchers found that higher levels of cleaved MASP-2 fragments resulting from MASP-2 auto-activation were produced in the presence of the N protein compared to non-N protein cultures. Similarly, the binding of MASP-2 to MBL was significantly enhanced in the presence of the N protein. C4 is a protein in the complement cascade that is cleaved to form the downstream products C4a and C4b. C4 hydrolysis (cleavage with water) and C4b deposition on cell surfaces were observed to be significantly potentiated in the presence of the N protein. When the serum of COVID-19 patients was collected and tested for various complement components, C5a stuck out as being significantly increased, especially in severe patients. C5a is part of a class of molecules called anaphylatoxins – along with C3a, another product of the complement cascade – which have the ability to induce inflammation and changes in vascular permeability, allowing leukocytes to migrate to sites of infection (Hugli, Muller-Eberhard, 1978). Taken together, this research suggests the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to aggressively activate at least one pathway of the complement system via its nucleocapsid protein. This mechanism presents verification for and supplements the essentially canonical hyperinflammatory response observed in early COVID-19. Inhibitors of the complement cascade such as C1INH or monoclonal antibodies directed against components of the pathway may be instrumental in treating the hyperimmune symptoms in patients.

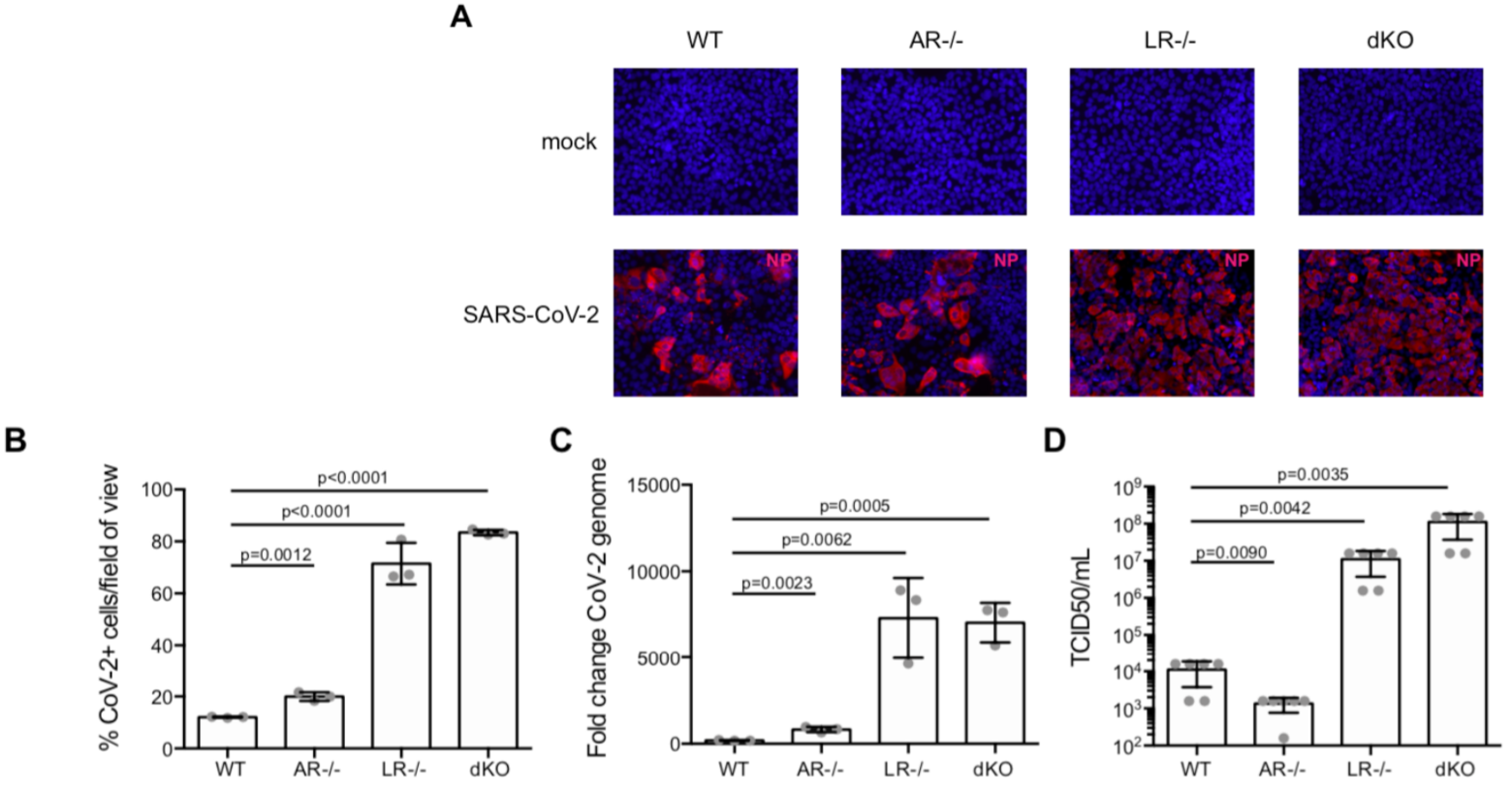

Interferon (IFN) is an important group of molecules that play a role in both innate and adaptive immunity (Ho, Armstrong, 1975). Typically, type I IFNs, secreted predominantly by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), are thought to play the largest part in fending against and clearing viral infection. However, the roles of IFNs type II and III have also been investigated. Here, Stanifer et al. investigated the type III IFN response in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this study, T84 IECs were knocked out for either the type I or type III IFN receptor, or both (double knockouts, “dKO”) and compared to wild type T84 cells that possessed functional receptors of both types. By knocking out the receptors, the researchers removed the capacity of the T84 cells to respond to type I or type III IFN. The cells were immunostained 24 hours post-infection with SARS-CoV-2 using an anti-nucleocapsid antibody. The results showed that the depletion of the type III IFN receptor resulted in a massive increase in cell infectivity, enhanced by a factor of roughly 7x compared to the type I knockouts and wild type cells. The type I knockouts exhibited only a “modest increase” in cell infectivity compared to wild type cells. In the dKO cells, an increase of roughly 7x was observed, reflecting the dysregulation of the type III IFN response in these cells. The increase in the number of infected cells upon depletion of the type III receptor was associated with significant increases in viral genome copy numbers in these cells, as well as with a 1000-fold increase in de novo synthesis of infectious viral particles. The importance of the type III IFN response in mediating infection in the intestine is thus highlighted by the significant increases in viral replication in the absence of these molecules. Future work will need to focus on characterizing the type III IFN response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in tissues outside the intestine.

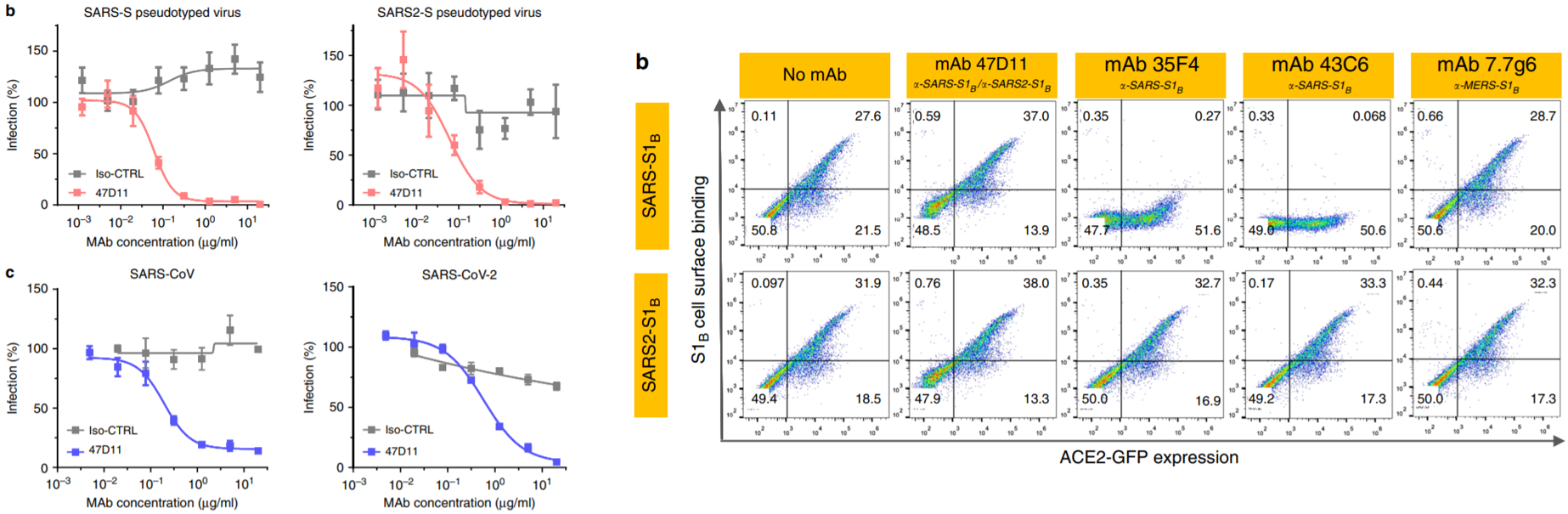

A paper from just this week (5/5) details the analysis of a neutralizing antibody that could potentially lead to breakthroughs in treatments for COVID-19. A group from the Netherlands screened 51 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) originally used against SARS-CoV-1 for cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein subunits. 4 out of the 51 displayed some cross-reactivity, while only one – an mAb called 47D11 – exhibited cross-neutralizing activity. The ability of the antibody to neutralize the spike protein is one of the most important factors in determining its efficacy for therapeutic use – some antibodies may be cross-reactive and bind to the virus, but to some surface that does not prevent the viral particle from gaining entry to host cells and replicating successfully. 47D11 inhibited infection of VeroE6 cells by SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 in both pseudotyped (with VSV) and authentic infections. Using ELISA, 47D11 was shown to target and bind the S1B subunit of the spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) of both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 with similar affinities (EC50 of 0.02 and 0.03 micrograms/milliliter, respectively). Of note, 47D11 binding did not compete with S1B binding to the ACE2 receptor, the known target for SARS-CoV-2 entry. Further analysis revealed that 47D11 seems to impair syncytia formation in both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 infection. The mAb thus neutralizes coronavirus infections via a yet unknown mechanism. However, the cross-reactivity of 47D11 indicates that it likely targets a conserved core structure of the S1B subunit, given the fact that the binding subdomain of the spike protein is largely heterogeneous across members of the coronavirus family. This would explain the inability of the mAb to compromise the spike protein-ACE2 receptor interaction. Importantly, the existence of this mAb opens possibilities for combination monoclonal antibody treatment utilizing antibodies against various subunits of the spike protein.

Written by: Parker Davis

Edited by: Jina Zhou and Esther Melamed

5/11/2020

References

Ballanti, E., Perricone, C., Greco, E., Ballanti, M., Di Muzio, G., Chimenti, M. S., & Perricone, R. (2013). Complement and autoimmunity. Immunologic Research, 56(2–3), 477–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-013-8422-y

Gao, T., Hu, M., Zhang, X., Li, H., Zhu, L., Liu, H., Dong, Q., Zhang, Z., Wang, Z., Hu, Y., Fu, Y., Jin, Y., Li, K., Zhao, S., Xiao, Y., Luo, S., Li, L., Zhao, L., Liu, J., … Cao, C. (2020). Highly pathogenic coronavirus N protein aggravates lung injury by MASP-2-mediated complement over-activation. MedRxiv, 2020.03.29.20041962. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.29.20041962

Ho, M., & Armstrong, J. A. (1918). Interferon. 5–9. www.annualreviews.org

Hugli, T. E., & Müller-Eberhard, H. J. (1978). Anaphylatoxins: C3a and C5a. Advances in Immunology, 26(C), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60228-X

Jensen, J. (1967). Anaphylatoxin in its relation to the complement system. Science, 155(3766), 1122–1123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.155.3766.1122

Karpman, D., Ståhl, A. L., Arvidsson, I., Johansson, K., Loos, S., Tati, R., Békássy, Z., Kristoffersson, A. C., Mossberg, M., & Kahn, R. (2015). Complement interactions with blood cells, endothelial cells and microvesicles in thrombotic and inflammatory conditions. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 865, 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18603-0_2

Noris, M., & Remuzzi, G. (2013). Overview of complement activation and regulation. Seminars in Nephrology, 33(6), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.08.001

Stanifer, M. L., Kee, C., Cortese, M., Triana, S., Mukenhirn, M., Kraeusslich, H.-G., Alexandrov, T., Bartenschlager, R., & Boulant, S. (2020). Critical role of type III interferon in controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection, replication and spread in primary human intestinal epithelial cells. BioRxiv, 2020.04.24.059667. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.24.059667

Wang, C., Li, W., Drabek, D., Okba, N. M. A., Haperen, R. van, Osterhaus, A. D. M. E., Kuppeveld, F. J. M. van, Haagmans, B. L., Grosveld, F., & Bosch, B.-J. (2020). A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. BioRxiv, 11(1), 2020.03.11.987958. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.11.987958

Leave a Reply