The archive for the acclaimed drama Mad Men, one of television’s most honored series in history, has been donated to the Harry Ransom Center. The donation was made by Matthew Weiner, the series creator, executive producer, writer and director; and Lionsgate, which produced the critically acclaimed series.

To mark this news, Weiner shares his thoughts on the value of archives, the show’s influence, and the storylines that got away.

Why did you choose the Ransom Center to house your Mad Men materials?

I was at the Austin Film Festival and visited the Ransom Center and its extraordinary Gone With The Wind exhibit as a tourist. We were at dinner that night with screenwriting team Michael Weber and Scott Neustadter and found out that Michael had overseen the donation of Robert De Niro’s archives. He gave me [Ransom Center Curator of Film] Steve Wilson’s contact, we went to the museum again, I found out that Gabriel García Márquez, Norman Mailer, and James Joyce had all been recently added, and from then on it was my hope to be part of such an amazing place.

What are some of your favorite things in the Mad Men archive that you look forward to people seeing?

In addition to every draft of every script and all the dailies of every episode, there is a wealth of props, costumes, and communication that represent not only the process but the key moments in the conception and execution of the show. We’ve also included all of our archival material, which is a wealth of period books, magazines, newspapers, maps, etc. covering more than the 10-year time frame that the show took place, which from what I can tell have been mostly thrown away by the general public.

You’ve talked about your early love of The Paris Review and learning as a teenager “how authors work”—the day-to-day work. These revisions, frustrations, and unglamorous moments are a substantial part of a writer’s archive. What inspiration have you found in the creative processes of others?

For some reason—part show business, part modesty—artists have traditionally hidden the long road of mistakes and missteps that lead them to finished work. Whenever you get a chance to see the road not taken, the cross-outs, the blunders, and sometimes the moment of inspiration before your eyes, you realize that it’s mostly encouraging. The ghosts of our heroes are as intimidating as their work, and anything that makes them human, not just their fallibility but their daily effort, can help you get through yours.

What do you hope researchers and visitors will gain from having access to the Mad Men archive?

It’s our hope that the Mad Men archive can provide both inspiration and edification. One of the things I learned about trying to represent the daily normal life of average people is that the impact of history can be negligible. We don’t know we are living in interesting times. We may assume we are, and we may have anxiety about the future. That’s human nature. But when you see the writers and artists attempt to recapture the texture of what is basically a very recent period, you understand that human life exists apart from history. In addition, I obviously hope that people who are creative can retrace our steps and see how we became interested in the parts of the story we were interested in, and that the creation of the characters and storylines in the show were the work of many people.

People say Mad Men generated a new Golden Age of television. You have referred to the 1950s as the original Golden Age of television and cited an interview with Stanley Kubrick noting that movies needed to be more like television; now, television is adopting many of the cinematic and structural styles of filmmaking. What are some of the changes you’ve seen in the evolution of television production and quality, including Mad Men’s own influence? Why do you think these changes are happening?

It’s true that the public is having an intense relationship with TV right now, but TV has changed and any comparison to the past has more to do with distribution and the marketplace. The only thing I can tell is that Mad Men’s existence was directly dependent upon the success of The Sopranos, which was, with a few exceptions, the first truly cinematic television show. TV has always been a blend of film and theater. That means we are able to see things happen, sometimes from a distance, and at the same time most of the story is moved by dialogue. The Sopranos, through David Chase’s imagination and an increased financial commitment to the medium he demanded, allowed for action and even personal moments to be told visually, not only with talking. The visual or cinematic is much more expensive. When The Sopranos became a success, it paved the way for a few things. First, it meant that serialized television was desired by the audience. A devoted fan, rather than watching 10 episodes of a 22-episode season would watch every single episode, sometimes more than once. Secondly, it confirmed that the audience was attentive enough to absorb the visual storytelling along with the talking in their living room. Mad Men did not have the budget of The Sopranos or obviously the prestige distribution and was shown with commercials, but benefited from the audience’s newly revealed interest in seeing every episode, tracking minor characters, and non-formulaic unfamiliar stories. The most interesting thing to me is that David Chase and I both have an interest in subtext: that is, things which are not said, dramatic irony, things where characters speak against the way they behave and other dramatic techniques that were traditionally believed to be beyond an American audience. If Mad Men has had an influence, it’s been in the tradition of both The Simpsons and The Sopranos in that it works on numerous levels: a story level, a historic level, and a personal level, all enabled by the creation of a complete world where everyone has a reason for what they’re doing. What is unique about Mad Men in my mind is that it doesn’t have a genre, and I’m proud of the fact that although it was very difficult, we told a story each week where the stakes were not beyond most of the audience’s everyday experiences.

Was there a storyline you wanted to pursue but that didn’t make sense historically?

Because the stories were told on a human level, we always found a way to put it in the context of those people’s lives. There were historical facts, believe it or not, that actually made our storytelling easier. We’re seeing right now how difficult it is to maintain suspense when people are in constant communication through cell phones, for example. We did have stories that the show rejected, frequently because they were too expensive or involved too many new characters, and were therefore too expensive. Also there was a question of tone. I remember specifically wanting to do a story about a couple of characters seeing a UFO. Due to the missile testing and early space program, there were more UFO sightings from 1960 to 1965 than there are either before or after. But the story I wanted to tell was that they had actually seen something. I had read an account of what I found to be a very rational, normal person who had seen a UFO and their reaction was fascinating to me because the event had called into question everything in their life that they knew to be true. In fact, they later claimed that it hadn’t happened at all because it was so destructive to their worldview and the view that others had of them. That was interesting to me and historically possible, but the writers persuaded me that it would be extremely damaging to the tone of the show. I should point out that on my end I was equally resistant to what became many of the key moments, for example, Betty sleeping with a stranger during the Cuban missile crisis. The writers—and I speak of them as a group but there are some in particular who really had such a profound role in the show—were incredibly talented and constantly creating dramatic avenues that never crossed my mind. On the other hand, when we were working out the first season, there was a moment in Episode 3 where Don is recognized as Dick Whitman on the commuter train. The writers pitched an idea to me that Don would go with the stranger under the guise of getting a drink to the bar car, and then between trains would push him to his death. This was a story we did not do because my immediate response was, “Don Draper doesn’t kill people.” Maybe the show would have been more exciting and felt more action-packed for those who always felt it lacked that, but for me, although Don has a far richer and more exciting life than I’ve ever had, there’s very little he’s done that most of the audience hasn’t done, whether they will admit to it or not.

Image: Matthew Weiner.

Related content

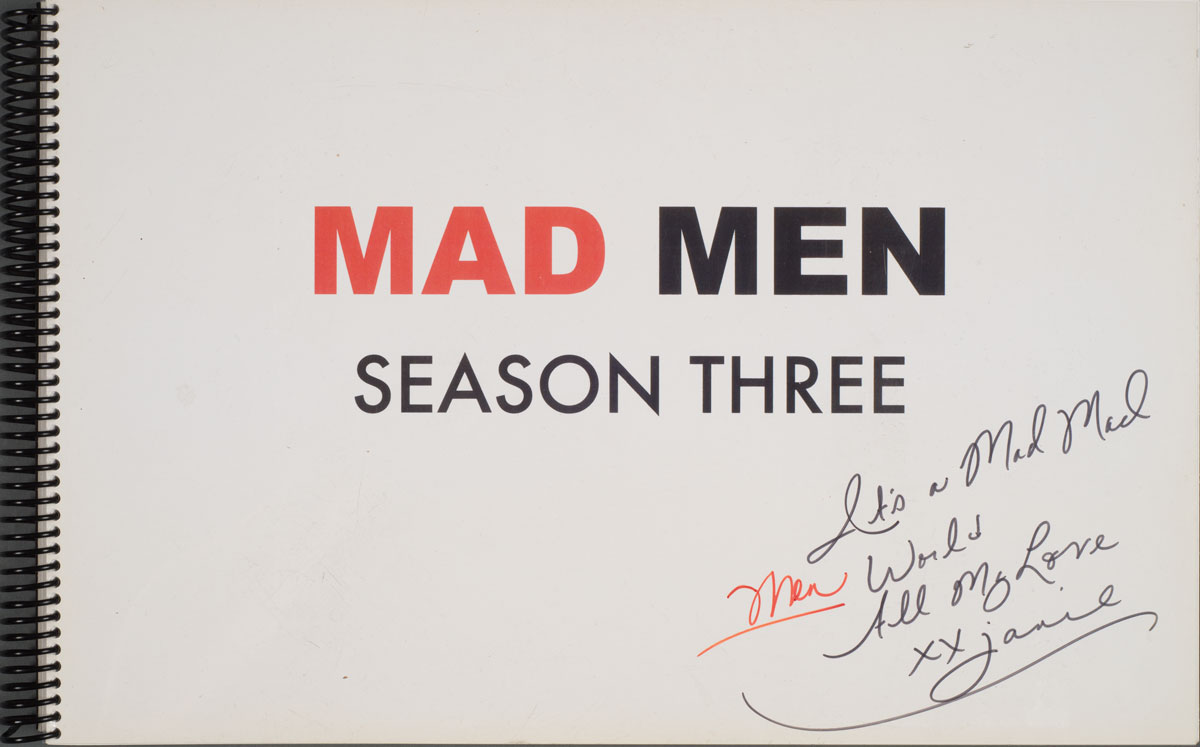

From Bond girls to Brooks Brothers, how Janie Bryant designed costumes for Mad Men

How Mad Men’s head of research mined the past for the show’s famous historical accuracy