The Gabriel García Márquez online archive represents an ongoing collaboration with students, professors, and scholars who visited the Ransom Center during the course of the 18-month project to consult the García Márquez papers. For me as the project manager, their feedback, including advice on what to add to the digital collection and what to emphasize, has been invaluable. Here, I speak to Alvaro Santana-Acuña, a sociology professor at Whitman Collection, Gabriela Polit, a professor in the Spanish and Portuguese department at UT, and José Montelongo, Mexican Materials Bibliographer for LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, about their experiences with the archive.

What’s one of the more unusual questions you were asked in an interview, and how did you respond?

José Montelongo: When the Gabriel García Márquez Papers were opened to the public, I was interviewed for Public Radio International and asked about how it felt to be one of the gatekeepers of this fantastic collection of documents. I mumbled some short answer, but I wish I had said something like, “We librarians don’t think of ourselves as ‘gatekeepers’ of this archive. We want as many people as possible to interact with the documents, to study the manuscripts and come up with relevant questions of the drafts and letters, to keep the conversation around García Márquez’s work alive and smart and animated. We are in charge of preserving the materials and establishing an order to facilitate consultations, yes, but our work only makes sense when students and scholars and critics and everyday readers engage with the documents. We want to be door openers, not gatekeepers. The García Márquez digital archive will multiply the opportunities for engaging with the papers.

Going back to that time, is there anything from the acquisition period itself — an item, person, or scenario, perhaps — that has stayed with you?

JM: We tend to think of the computer and the word processor as a killer of manuscripts. You save changes on top of your working document and the previous draft is lost. It´s remarkable, in the case of García Márquez, that when he began working on a computer in the mid-1980s he also began to keep more and more drafts. He wrote on the computer, printed out the pages, made corrections by hand during the evenings, and gave the corrected draft to his secretary to incorporate the changes. Either he or his secretary or his wife started keeping the drafts instead of destroying them, as he had done during the earlier part of his career, and that’s why we can now peek into García Márquez’s creative process, look over his shoulder, as it were, and see the discarded words or paragraphs, the additions and insertions—the artisanal work of the writer as the first editor of his own stories.

Can you tell me a bit about how you teach with the collection?

Gabriela Polit: Among my current students, responses are different. Some say that they are not familiar with Garcia Márquez’s writing. Some say that they know their parents have read his works. Students who have Spanish-speaking backgrounds know who he is, and some have read his works. Students who took Spanish in High School are familiar with his short stories or short novels. When I teach (in English) to this diverse population, my aim is to familiarize them with his work, and help them enjoy his prose, as well as teach them about his role within the wider Latin American literary scene. After the class has read his books, I bring them to the Ransom Center to show them materials from his archive. During the visit, I explain how the papers arrived at UT, and the importance of the fact that we have this collection. So far, I have had great responses from students.

When I teach advanced courses, I mostly discuss issues related to my current research, which is the relationship between journalism and literature. García Márquez is a crucial figure in the changing world of written journalism in Latin America, not only because of the legacy of the FNPI (Foundación Nuevo Periodismo Iberoamericano), but also because he always insisted that he was a journalist. That was the craft that he loved. The effects of his commitment to journalism have had a tremendous impact on current discussions about crónicas (non-fiction works), and the literary world, as well as the role of what I call the journalist as an author. Looking at the lawsuit that Luis Alejandro Velasco filed against García Márquez for the copyrights of The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor serves as an interesting entry into thinking about the law, the literary act, non-fiction as a literary genre, and the role of the author. All these elements are always at the core of debates about Latin American literature, in which the production of discourses (fiction or non-fiction), and the voices of their creators, are traditionally read and discussed in relation to the social reality the authors represent. The papers of the lawsuit are in the archive.

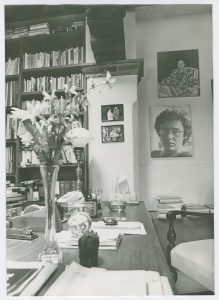

The archive also sheds light on the way in which García Márquez shaped the field of literary studies. He was not only a great writer but an intellectual committed to the social and political realities of his time. Traces of this commitment are all over the archive, in the pictures, the correspondence, the annotations of his scrapbooks. The material has historical meaning and enables me to teach literature as I understand it, as a meaningful dialogue with our history.

In an interview with Ilan Stavans, García Márquez spoke about planning “the exact number of pages in each chapter and in the book as a whole” before beginning to write a novel. He said that a “single noble mistake in these calculations would oblige me to reconsider everything, because even a typing error disturbs me as much as a creative one.”

Did you see evidence of this fastidiousness when you read through his typescripts of One Hundred Years of Solitude? What kinds of edits was he making as the novel approached its final form?

Alvaro Santana-Acuña: García Márquez edited One Hundred Years of Solitude relentlessly before its publication in May 1967. The truth is that in August 1965, when he started writing the final version of the novel after several unsuccessful attempts, the undecided writer changed his mind numerous times about the plot, timeline, characters, and length.

The final typescript of One Hundred Years of Solitude, kept at the Harry Ransom Center, is 490 pages long. García Márquez finished it in August 1966. About a year earlier, in an interview with the leading Venezuelan newspaper El Nacional, the writer announced that his new novel would have 800 pages. Later, in a letter dated October 30, 1965, he offered the novel for publication to Francisco Porrúa, acquisitions editor of Sudamericana Press, who published it. In his letter to Porrúa, García Márquez indicated that the novel would have 700 pages and that he had written 400 pages so far. (This letter is available at the Harry Ransom Center.)

In November, after the first month of full-time work on the novel, he figured out its actual length: between 400 and 500 pages. This is the number that appears in a letter he sent that month to the Argentine writer Luis Harss, who interviewed him during the summer for the volume Into the Mainstream: Conversations with Latin American Writers (1967).

García Márquez revised the length of the novel because, by late November, he had decided on the novel’s plot.

In the El Nacional interview, published in October, García Márquez said the novel had no title. He was probably telling the truth because, at that time, his idea was that the novel’s plot would cover three or four centuries. As he said to the El Nacional journalist, the novel is:

the public and private history of a certain family in a Caribbean town, of its greatness and its misery, of its deserved frustrations, of its tragic destiny from the Colony to the present time. The first generation of that family founded the town, the second was ruined by the War of Independence, the third promoted 32 civil wars and lost them all, the fourth revolted the workers against the injustices of the banana company and the result was a massacre, the fifth conquered power without intending it and did not know what to do with it; and the sixth became extinct in the nostalgia of its past greatness. The last descendant of the lineage shot himself tormented by solitude, in a town already transformed into an enormous and hot African city, where nobody knew him. In absence of a name, the authorities put the number of the judicial file in his grave.

As this quote reveals, several main points of the plot were in place in October. The novel was a historical tableau set in the Caribbean that followed a family across several centuries. The influence of Alejo Carpentier’s novel Explosion in a Cathedral (1962) was clear, too. (In a letter kept at the Harry Ransom Center sent to writer Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, García Márquez was so impressed by Carpentier’s novel that he called it “a masterpiece of world literature.”) But there were key points missing as well. In the interview, García Márquez mentioned nothing about characters’ fear of incest, the name of the town, Macondo, or the name of the family, Buendía. More importantly, a key character was missing: Colonel Aureliano Buendía.

Just a few weeks later, in November, García Márquez explained in the letter to Harss that One Hundred Years of Solitude, “It is not only the story of Coronel Aureliano Buendía, but also the history of his entire family, from the founding of Macondo, until the last Buendía commits suicide, one hundred years later, and the lineage runs out.”

There are consequential differences between his descriptions of the novel in the El Nacional interview and the letter to Harss. In this letter, García Márquez mentioned Macondo as the location of the novel, which focuses on the Colonel and was the century-long story of the Buendía family from the founding of Macondo to its disappearance. In addition, unlike he said to the El Nacional journalist, the War of Independence did not ruin the second generation, the fifth generation did not conquer power, and Macondo did not become an African city.

Between the El Nacional interview and the letter to Harss, that is, between October and November 1965, García Márquez understood how to add the character of the Colonel to the novel—the unnamed Caribbean family turned into the Buendías and this change paved the way for the Coronel’s central role in the plot. The writer also realized that the story would not begin during the colonial era but at a later time, with the founding of Macondo. With these and other changes, he could reduce the length of the novel from three or four centuries to one century. He could then cut almost by half the amount of pages the novel would have in the end.

That inserting Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s story into the novel was García Márquez’s major breakthrough is further proved by the fact that, in the El Nacional interview, he stated that the third generation promoted the thirty-two civil wars and lost them all, while in the letter to Harss it was the Colonel himself, member of the second generation, who famously promoted the thirty-two unsuccessful armed uprisings.

In sum, what happened between October and November 1965 was a giant leap for the writer, but a small step for the novel. What followed until August 1966 was the immense work of writing, rewriting, and editing, which the García Márquez Archives at the Harry Ransom Center permit researchers and curious readers to discover.

Related content:

Thousands of images from Gabriel García Márquez archive now online

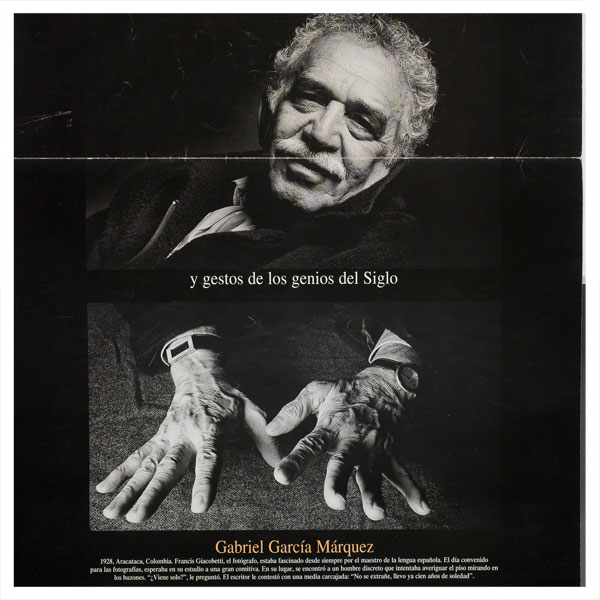

Gabriel García Márquez’s life in 100 pictures

The magically real digital archive of Gabriel García Márquez

Award supports digitization of more than 24,000 images from the Gabriel García Márquez archive