Author, journalist and screenwriter Aaron Latham has donated his papers to the Ransom Center. Latham shares insight about materials in his archive, ranging from his detailed journal of the writing and creation of the film Urban Cowboy to interviewing former chief of CIA Counterintelligence James Angleton. Once cataloged, Latham’s materials will be accessible for research.

Leigh Hilford: In a journal in your archive, you’ve written that you want to tell “journalistic stories thru the vehicle of love stories.” What is the significance of the love story on your writing?

Aaron Latham:

I’ve been lookin’ for love

In all the wrong places…

–song in Urban Cowboy

For a good many years now, I have been living that song, looking for love, sometimes in the wrong places, sometimes in the right ones. I have been looking for love stories to write about.

I first tried this technique when I was a senior editor at Esquire magazine back in the late 70’s. One night I got a phone call at 3 o’clock in the morning from my peripatetic boss, the fabled Clay Felker with my next assignment. He wanted me to catch the next plane from New York to Houston to do a story on a honky-tonk with something brand new (back then): a mechanical bull like they train rodeo riders on.

The next evening, I approached Gilley’s saloon warily. The place had a reputation for attracting a rough crowd. As I walked through the swinging double doors, I suspiciously surveyed the customers. Since I was from Texas, I felt as if I were walking into a family reunion. But I also felt like Margaret Mead stepping ashore on Tahiti for the first time. Looking for love and looking out for trouble, I plunged in.

For a long time, I had wanted to write nonfiction, New Journalism love story. I knew that the New Journalism meant using the tools of fiction to tell a nonfiction story. Tools like writing in dramatic scenes and using point of view. But I felt the love story could be a powerful tool too. After all, most fiction is powered by love.

Love turned out to be as hard to find in Gilley’s as it is in all them country songs. The biggest problem was Clay who wanted our cowboy to work in a refinery. Every time I would find a cowgirl pretty enough to be on the cover of a magazine, she was dating some guy who bagged groceries. I was losing heart when around midnight a pretty girl walked in and rode the bull standing up. Holding my breath, I asked her what the man in her life did for a living.

Installs insulation.

Oh no! Where?

At a refinery.

Oh yes!!!

Then she told me that she had met her husband at Gilley’s, they had their wedding reception at Gilley’s, they broke up because he didn’t want her to ride the bull at Gilley’s, and he met somebody new at Gilley’s. Just like a country song.

You kept a detailed journal of the writing and creation of the film Urban Cowboy. What insights do you hope students and researchers will learn from this journal?

I thought that if I ever wrote a Hollywood novel, a Hollywood diary might be a helpful thing to have around. But mainly, I just didn’t want to forget anything. I knew I never was going to make my first movie again. And you always remember most clearly the first time you do something. Think about it.

But what I didn’t intend ever to do is let anybody else read it. That would be too embarrassing for me and my friends and enemies. So I never expected anybody to learn any lessons from the diary because I never expected anybody to see it. Obviously, 39 years later, I’ve changed my mind. Even the State Department decodes its secrets every half century or so.

How did your writing process change from penning the article that inspired “Urban Cowboy” to writing the screenplay?

In the beginning, I wrote 50 pages just to see if I could. I told myself that I had done pretty well for a wet-behind-the-ears neophyte. This screenwriting racket wasn’t going to be so hard after all. I even expected to hear some praise as I handed my pages to Jim Bridges, the brilliant director of The Paper Chase and The China Syndrome and the soon-to-be Urban Cowboy. Unless I screwed it up.

Jim read the pages. He looked up. He looked down.

He smiled at me and said very slowly: “First of all, most screenplays are not written in the past tense.”

Well, at least now I knew one way that writing for the movies is different from writing journalism.

There are of course many other ways. One of the most important is your attitude toward the world. Journalists are about what’s wrong with the world, by and large. Tiger bites man. That’s a story. Lots of tigers don’t bite men. No story. Movies aren’t exactly about what’s right with the world, but more in that direction. Because movies usually have heroes and heroines who are trying to fix up their world. So we “root for” them. You certainly don’t root for the people in the newspaper every morning. This all takes some serious rethinking if you’re a lifelong journalist.

Can you tell us about the writing process for your novel Orchids for Mother? How did you approach interviewing a person like James Angleton, former chief of CIA Counterintelligence, to gather information for your novel?

This is how I met my Mother.

In early 1976, the Central Intelligence Agency was accused of conducting illegal spying operations in this country. The man at the center of the controversy was James Jesus Angleton—the head of the Counterintelligence Department—whom the CIA made a scapegoat and fired.

I decided to try calling Angleton. I knew he wouldn’t talk to me, but I felt I should try anyway. Somehow I got his number in Arlington, Virginia, and dialed it.

Angleton himself answered.

I told him that I was a reporter for New York magazine doing a story on the CIA.

He didn’t hang up as I had been afraid he might. But I heard a lot of clinking and clunking on the other end of the line. I assumed he was attaching his tape recorder to the phone. I already had mine hooked up.

I asked Angleton if he could tell me anything about why he had left the agency.

He said he couldn’t talk about he agency.

There was an awkward pause. I felt I was about to lose him.

“Well, if you can’t talk about the CIA,” I said, “what about poetry?”

I knew from reading about him that Angleton was an avid reader of modern poetry. This passion began at Yale, where he edited a literary magazine and had continued ever since.

The spy and I talked about poetry for at least twenty minutes. One of the themes of our conversation was: Had Ezra Pound and T. S. Elliot been good or bad for poetry in the long run? We both agreed that they had been great poets, but we wondered if they had started poetry down a rather barren path. I felt as if I were a sophomore in college again.

When I ran out of anything else to say about modern poetry, there was another awkward pause. It finally occurred to me to ask him about his orchids, which I had read about in news reports.

So we talked about orchids for at least ten minutes. I asked him how one goes about growing orchids. I had not realized how many steps were involved or that an orchid can take 15 years to bloom. The answer to my question was longer than I had anticipated and my ear was starting to hurt.

I decided it was time to end the conversation. I told Angleton it had been nice talking to him and I would call him back in a few months to see if he could talk about the agency then.

“Well, maybe we can talk a little about the agency now,” he said.

And we did. We talked on and on and on. I was delighted, but at the same time my ear hurt worse and worse, and I was supposed to meet my future wife, Lesley, for dinner, and I was late.

“Thank you very much,” I said. “This has been helpful.”

But Angleton did not take the hint. He kept on talking and talking. Then the tape in my recorder ran out.

“Well, I guess that’s about it,” Angleton said. “Good-bye.”

I am sure that the tape had just run out in his tape recorder, too. He had not been able to stop talking while there was still a little tape on the spool because that would have been wasteful and sloppy.

A few days later, I received a large manila envelope in the mail. Opening it, I found an eight-by-ten photograph of e. e. cummings standing in front of a fireplace. I was puzzled. Turning to the enclosed letter, I found that it was from Angleton, signed in his tiny microdot handwriting. The letter informed me that Angleton himself had taken the picture. It went on to describe and give the history of every object in the photo—all the knickknacks on the mantelpiece, the painting on the wall, on and on. At the very end of the letter, Angleton wrote that I had “been seen” in Washington recently. He suggested that we have lunch the next time I came to the capital.

I called him and made a lunch date.

We met at his favorite restaurant, La Niçoise, where all the waiters wear roller skates. Sitting beside me, Angleton, who is literally as well as figuratively twisted, seemed a fabulous character who had come in, not from the cold, but from the world of fiction.

When I sat down to write, I decided to do a fictional short story, not a straight journalistic piece. I reasoned that the CIA was itself in the fiction business since it was always making up cover stories to cloak its true intentions—and one way to fight fiction is with fiction. At the centre of my short story would be a veteran spy who grew orchids and worried about modern poets. I made up some things but not his code name: Mother.

Related content

Journalist, Screenwriter Aaron Latham Donates His Papers

Top image

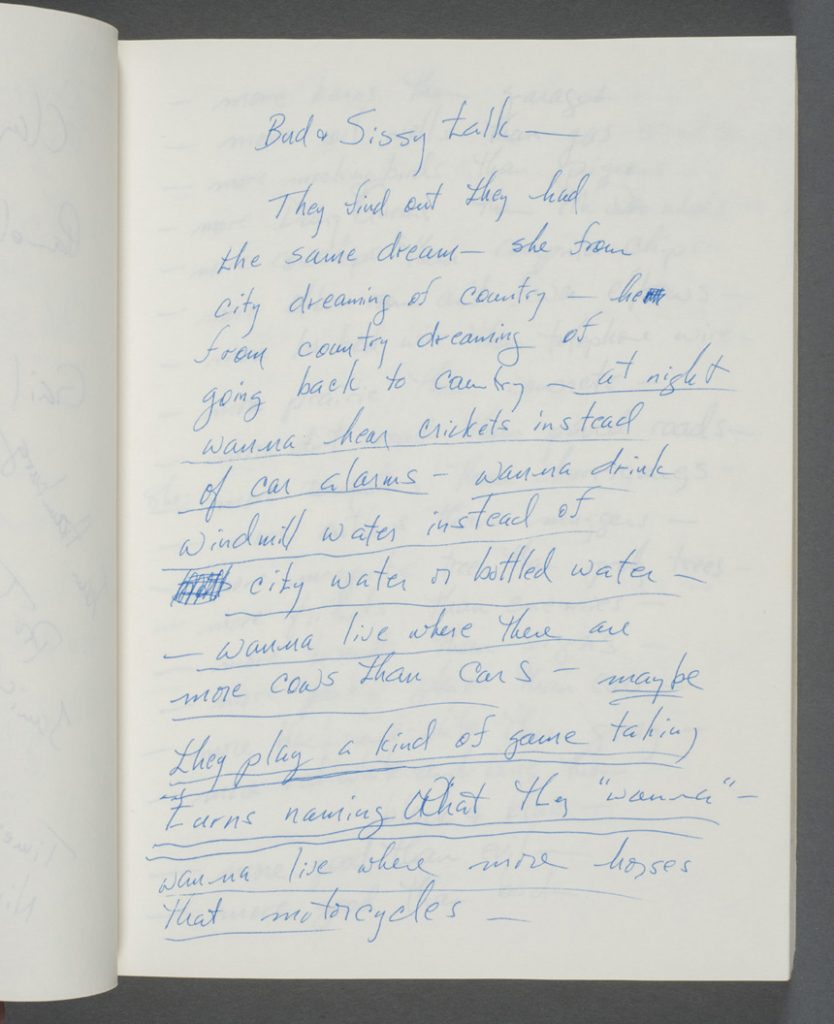

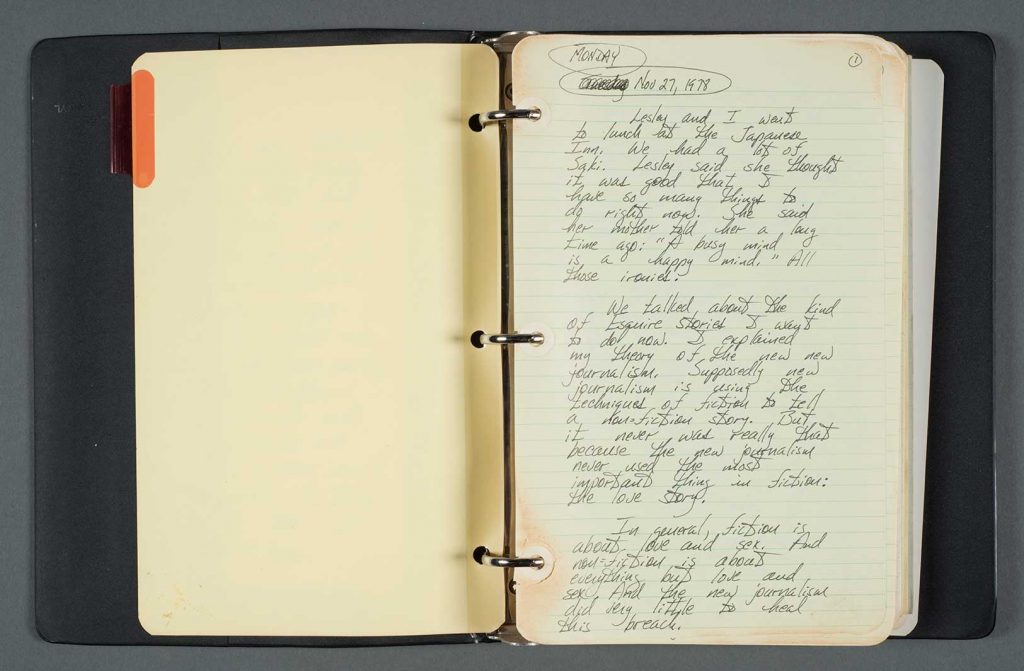

Aaron Latham’s multi-volume diary relating to the production of the film Urban Cowboy, November 27, 1978–November 25, 1979. Photos by Pete Smith. Aaron Latham Papers, Harry Ransom Center.