Kathleen (Katy) Telling is a Plan I Honors Junior at The University of Texas at Austin, majoring in History and French. She’s taking Dr. Robert Abzug’s “Religion and Psychology in Modern American Culture,” which meets periodically at the Harry Ransom Center.

Arthur Conan Doyle

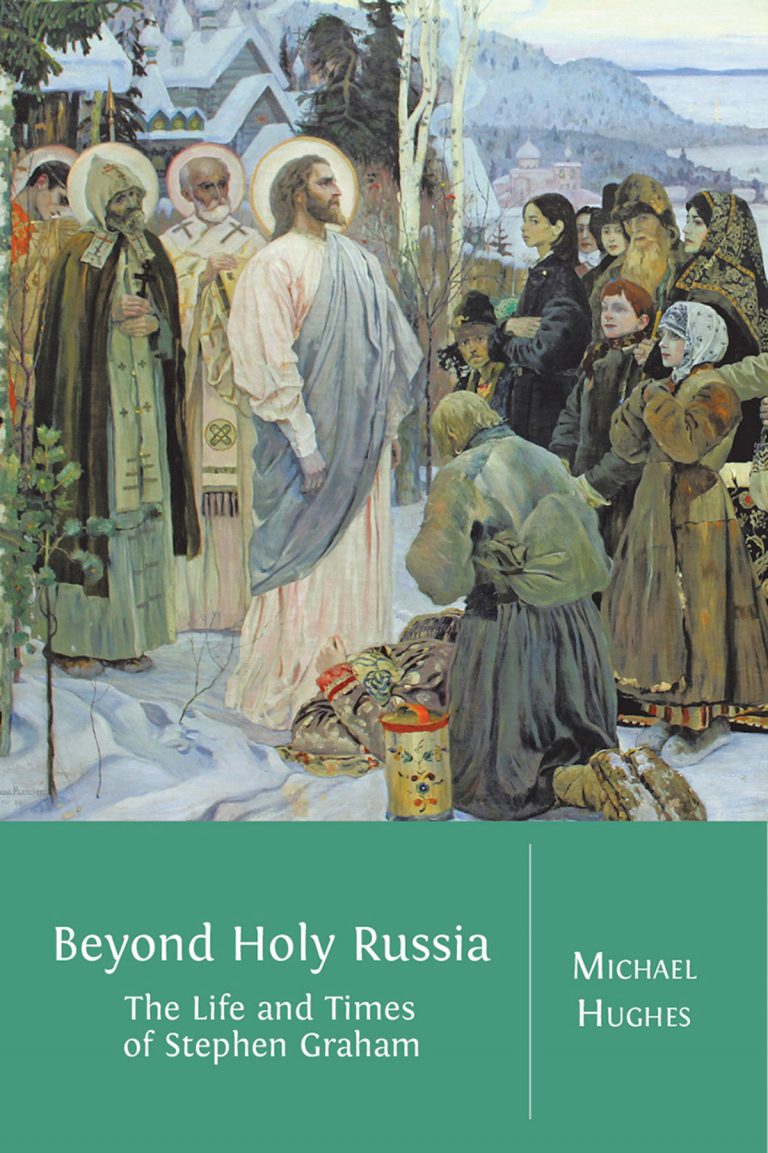

Recent biography sheds light on world-traveler and writer Stephen Graham

Stephen Graham was a British traveler and writer largely responsible for shaping British and American perceptions of Russia in the early twentieth century. He later traveled throughout Europe and North America, writing many novels and biographies that established him as an important author during his lifetime. Graham’s work, however, is… read more

Sherlock Holmes’s Infinite Case-Book

Many of the items discussed here are featured in the display “The Intertextual Sherlock Holmes,” which can be seen outside the Reading and Viewing Room on the second floor of the Ransom Center until April 21. While fanfiction may seem like an Internet-dependent phenomenon, its origins stretch far back into… read more