Kathleen (Katy) Telling is a Plan I Honors Junior at The University of Texas at Austin, majoring in History and French. She’s taking Dr. Robert Abzug’s “Religion and Psychology in Modern American Culture,” which meets periodically at the Harry Ransom Center.

I never thought I would have a beef with Alfred A. Knopf. For one, the thought of sharing a single line of my past angst-ridden ninth grade attempts at creative writing as published “literature” genuinely slows my heart rate to a complete rest. For another, the gentleman in question passed away in 1984, eleven years before I was born, leaving my indignance, perhaps, too little too late.

And yet, here I was, rolling my eyes at the Knopf publishing house’s rejection letters of psychologist Rollo May’s recently completed manuscript “Modern Man in Search of Himself.” “Who did these men think they were?,” my nose crinkling in righteous disagreement, “Had they read the book at all?” I was fuming, I was bothered, I was…defensive? Defensive on behalf of this man whose name I had never even heard of until two weeks ago?

Such is the absurd profoundly human reach of archives and the stories they can tell. Accessing collections brings the lives of individuals whose experiences may otherwise seem no more personal than a Wikipedia page back into the present moment, teaching you, comforting you, or, in my case, annoying you. Luckily, I had an entire class dedicated to facilitating these instances of connection.

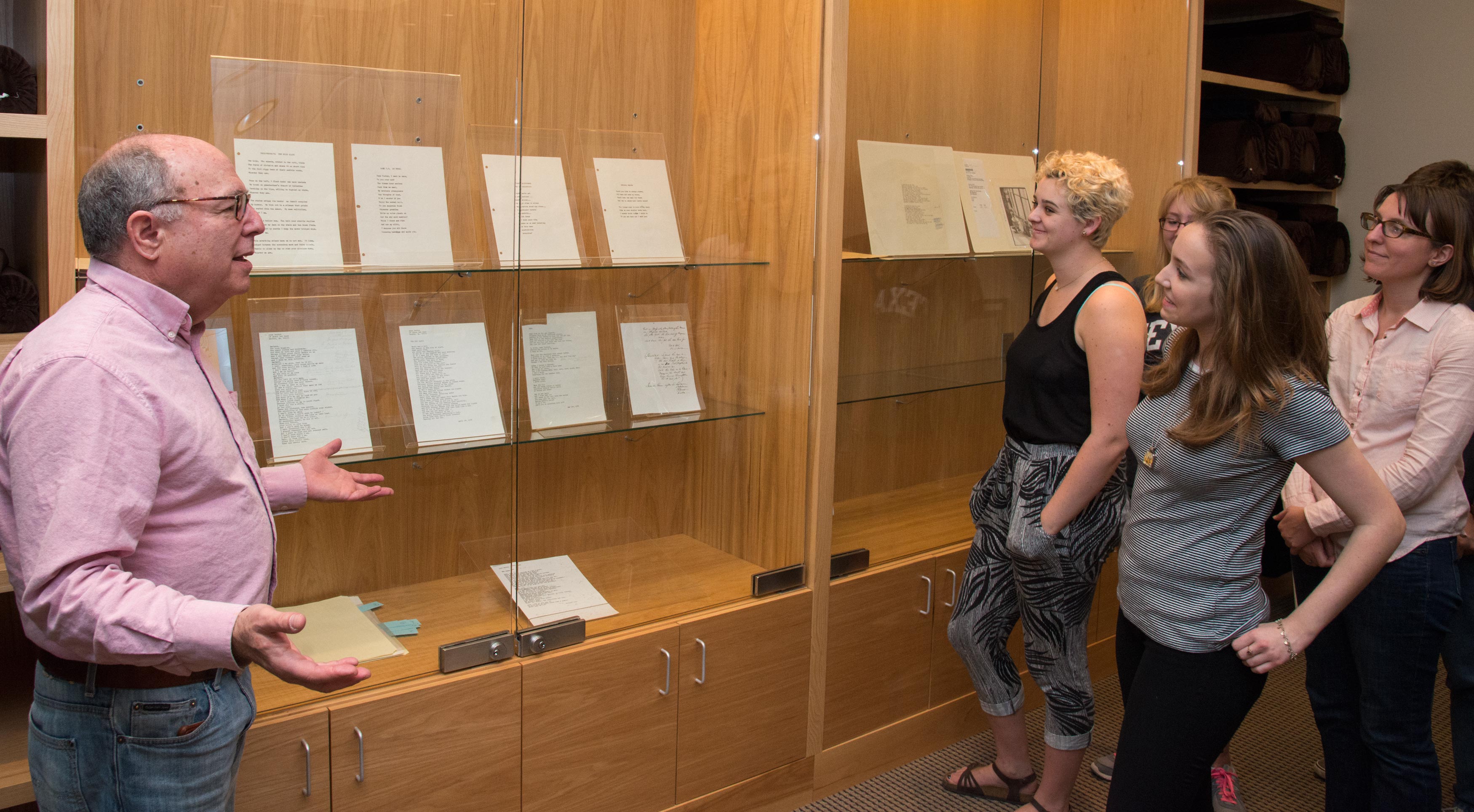

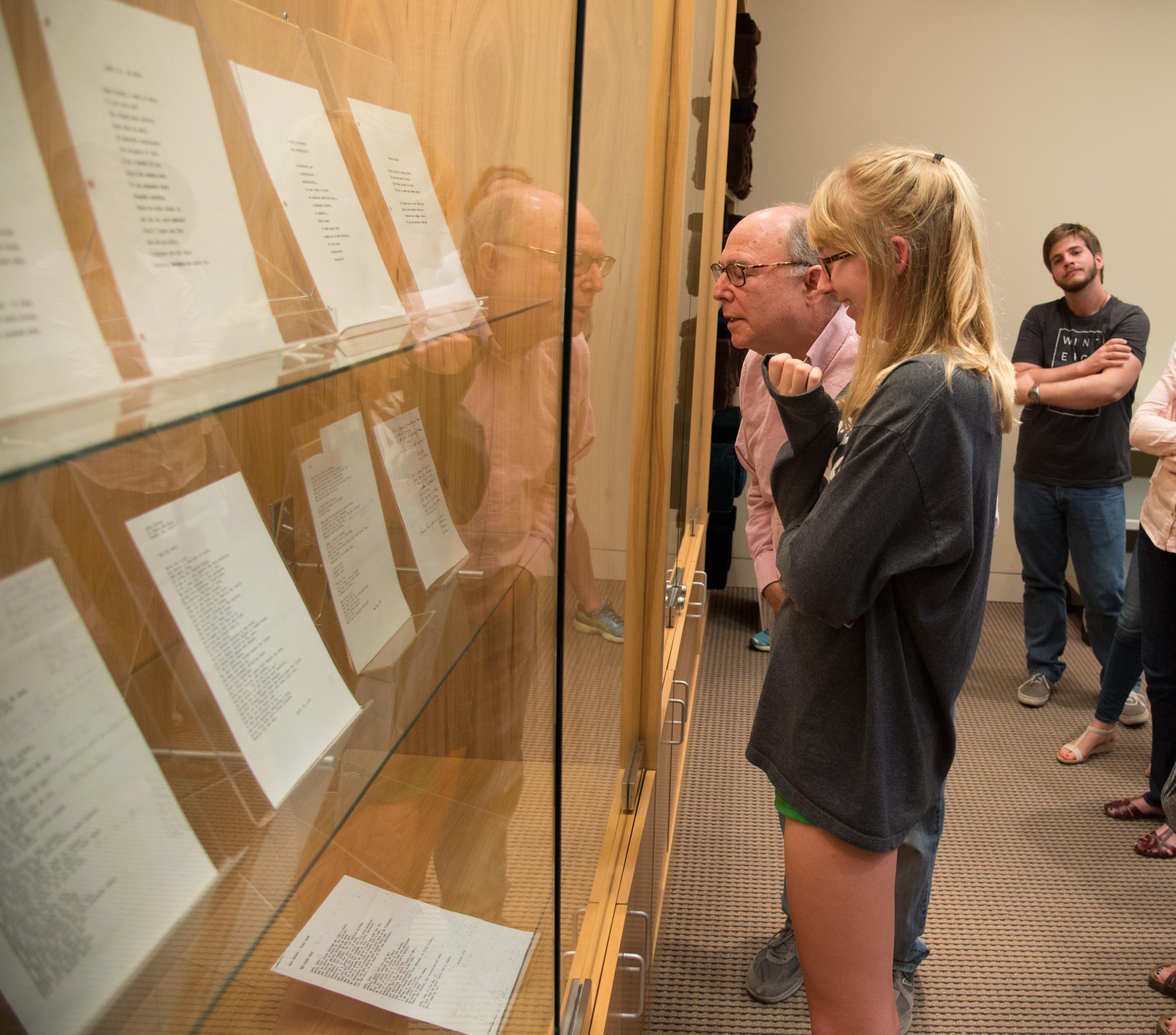

This semester I’ve had the pleasure of taking Dr. Robert Abzug’s “Religion and Psychology in Modern American Culture.” Each Tuesday, our class meets in the College of Liberal Arts building to unpack (as best we can) the works we have been assigned to explore. Every Thursday, though, the subjects we discuss at length in class have leaped out of their modern-day reprinted bindings and into the softly lit shelves of the Ransom Center’s Feldman Room. Showcased in these shelves are related archival material Dr. Abzug selects weekly for our class to view.

For me, the Knopf materials undoubtedly elicited the strongest response, as I had days prior fallen for Rollo May’s invitation to live courageously, be vulnerable, and embrace the reality of mortality. As a reader with an appetite for irreverent prose and biting satire (nonfiction or otherwise), it’s not often I fall for the tenderness of an author’s writing, and I was feeling particularly defensive of May. Needless to say, I rankled under the haughtiness of the rejection letters.

However, the Knopf materials were only the tip of the iceberg. For my classmate Sarah Stahl, the connection to the class and Ransom Center collections came about in an entirely different way:

“I love going to the Ransom Center for class because it makes learning about the authors more interesting. When we got to see the first edition of “Leaves of Grass” (1855), one of which is signed by Walt Whitman, it made Whitman seem more real and personable. I felt like I developed a deeper understanding and connection with the author that I wouldn’t have had if we just read the book in a classroom.”

For Junior Rachel Landman, it was the materials Dr. Abzug first pulled for the class that piqued her interest:

“I really enjoyed the Ransom Center’s collection of phrenology reports. Phrenology is a really interesting and fairly short time in psychology and psychotherapy history, and I loved seeing a real piece of that history in person.”

What’s striking about the diversity of our responses is that they reflect the diversity of materials housed in the Ransom Center and how unpredictable connections with materials can be. For the three of us, the eureka moment was found in the acerbic rhetoric of a prestigious publishing house, the esoteric stanzas of a transcendentalist poet, and the peculiar diagrams of phrenological reports. For others, those ineffable moments of understanding of the past could have come from Carl Jung’s correspondence, or Spiritualist photography doctored to depict a young English woman communing with fairies in her lush backyard garden, an oddity pulled from the collection of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

This class, one way or another, one archive or another, brings the fields I am encountering for the first time before my eyes, providing a tangible timeline through history. Not only has this experience left me with a greater respect and appreciation for the study and history of psychology and religion as a whole, but has also granted me the opportunity to forge new relationships with past lives. That link-forging is at the heart of humanities research, and it has been the joy of taking of this class.

As for Knopf, I have to cut him some slack. After all, it was his publishing company and not the man himself who was giving the work of my newfound favorite psychologist the boot. May’s work was predicated upon the study of modern man’s anxiety, and negative reactions to a book which deviated from the usual tone of contemporary psych publications were perhaps illustrative of the concepts May sought to better understand. Certainly, not everyone has to fall in love with the words and ideals of Rollo May, or those of any writer, for the matter. And as a student of the humanities, I can learn to forgive a little historic pretension.

At least, just this once.

Related content

Bringing undergrads into the thick of research

Receive the Harry Ransom Center’s latest news and information with eNews, a monthly email. Subscribe today.