by JAMES ARNETT

“Why was it so hard to see while it was happening that that was what was happening?”

—URSULA K. LeGUIN, In and Out [1]

“What’s ‘it’–what do you mean by ‘it’?”

“O, anything–I mean–you know what I mean.”

—VIRGINIA WOOLF, Kew Gardens typescript

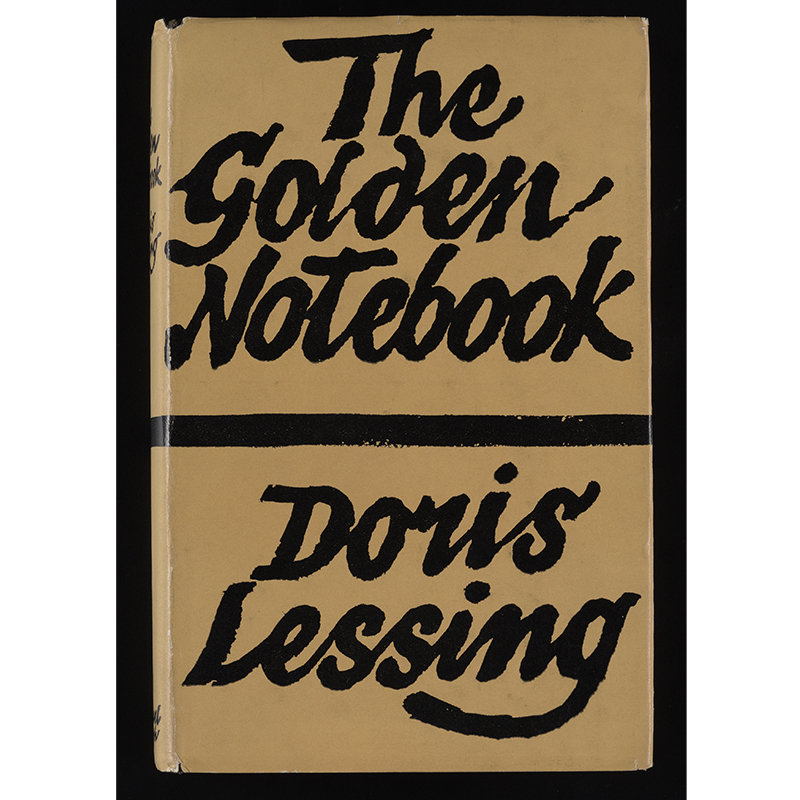

The walls have closed in in my Tennessee home. I sometimes stand up blinking from my screen and walk from room to room, unsure of what I’m looking for or doing. My corgi, Phineas Finn, is no help, certain that if I am at home I am at his service. I stand in my front window often, looking at the unchanging suburban street. I retreat to the refuge of books. [Read more…] about Thoughts during a pandemic on Doris Lessing, Virginia Woolf, and what ‘it’ is