The atria on the first floor of the Ransom Center are surrounded by windows featuring etched reproductions of images from the collections. The windows offer visitors a hint of the cultural treasures to be discovered inside. From the Outside In is a series that highlights some of these images and their creators.

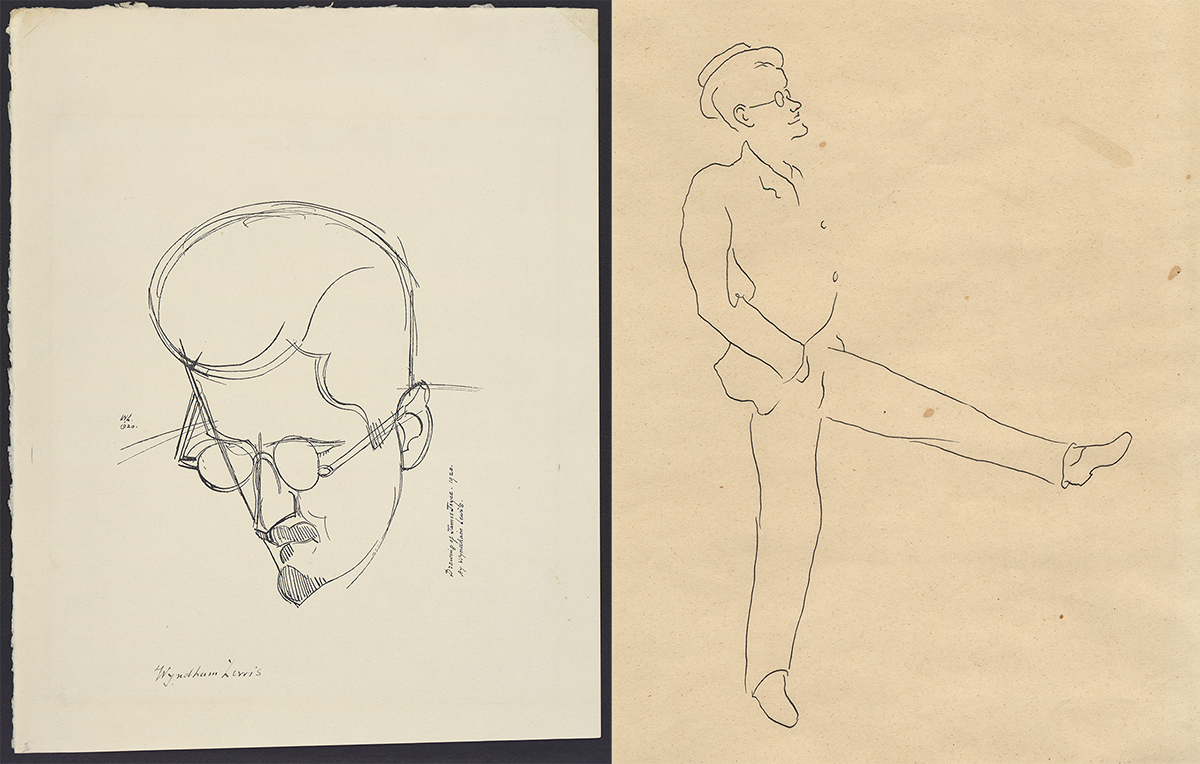

The windows of the Harry Ransom Center show two drawings of James Joyce, one by Desmond Harmsworth and one by Wyndham Lewis, depicting very different sides of the famous writer. The Lewis drawing, dated 1920, shows a portrait of Joyce from the outside: head down, identifiable by the thick eyeglasses and small beard. Lewis was one of Joyce’s Modernist contemporaries—a novelist, experimental artist, and founder of the abstract art movement Vorticism. He was also a well-known curmudgeon and critic, and his sketch hints at the distance from which he approached his fellow artist. Harmsworth, in contrast, was one of Joyce’s publishers and enjoyed long evenings talking and drinking with the writer. His drawing expresses more of Joyce’s personal character.

[Read more…] about From the Outside In: Two portraits of James Joyce