*This post discusses an historical event and uses terms and vocabulary that may feel out of date to some readers. We acknowledge that terms are constantly evolving and certain terms have been abandoned or expanded by the communities that use them for good reason. However, for this post the decision has been made to use the vocabulary of the sources from which information was pulled. For more information on current terms, please visit the Gender and Sexuality Center’s Glossary.

This Friday marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, a major catalyst for the Gay Liberation movement and the fight for LGBTQIA+ Rights. In honor of this occasion, the UT Libraries Diversity Action Committee would like to highlight a couple of pieces in our collection to contextualize this historical event.

The Stonewall Riots

Tony Lauria, the son of a Mafia boss, three of his childhood friends, and Matty Ianello, another member of the Mafia, first opened the Stonewall Inn on March 18, 1967 (Carter 2004, pg. 1). Like many gay bars of the 1960s, the Stonewall Inn was a “bottle club” that sold alcohol to private parties and did not require a liquor license (Bausum 2015, pg. 24; Carter 2004, pg. 68). The lack of a license made these businesses the targets of frequent police raids, so the Mafia bosses who ran these clubs made weekly payments to the local police precinct to avoid being raided (or at least receive warning in advance of a raid) (Bausum 2015, pg. 25). The Mafia owners would then make a profit on overcharging for watered-down drinks and not maintaining proper sanitation (Bausum 2015, pg. 5).

Despite these conditions, Stonewall quickly became a popular place for the gay and transgender communities to dance, drink, and socialize. Before it became legal, the Stonewall dancefloors were one of the few places that allowed same-sex couples to dance together (Bausum 2015, pg. 6). Its placement on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village also generated plenty of foot-traffic, so there was always a crowd on Friday and Saturday nights (Bausum 2015, pg. 27).

At 2:00 AM on June 28, 1969, a police team led by Inspector Seymour Pine raided the Stonewall Inn with the intent of arresting the employees, the mafia members, and those who were not wearing at least three pieces of gender-conforming clothing. Some of the patrons who were allowed to leave stayed outside the bar and were joined by friends and pedestrians. The crowd cheered at the arrest of the Mafia members, but they became angry when the police began arresting the drag queens. According to several witnesses, the crowd finally rioted when a lesbian patron managed to escape the police car, and the police roughly shoved back her inside (Carter 2004, pg. 150-153). Many of the officers left by taking the full paddy wagons to the nearest police station, but a small group hid with Inspector Pine inside the Stonewall Inn. Eventually, the Tactical Police Force (TPF) arrived to gain control of the rioters. After two hours, the crowd dispersed, the police left, and the riots ended (Bausum 2015, pg. 37-64). For the next four nights, people gathered, protested, and organized on Christopher Street. Several activist groups joined together to create the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) (Segal 2019, pg. 132).

In the following months, pamphlets such as “Get the Mafia and Cops out of Gay Bars” by Craig Rodwell and “The Hairpin Drop Heard Around The World” by Dick Leitsch spread news of the riots and gathered support for the rapidly expanding Gay Liberation Movement. On July 27th, a protest gathered in Washington Square Park and marched to the Stonewall Inn in celebration of the riots and political activism in the month after the Riots (Bausum 2015, pg. 74). A year later, Craig Rodwell organized the first Pride Parade from Christopher Street to Central Park on the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

Today, Pride Parades are still held annually during the months of June, July, and occasionally August and celebrated with a surge of rainbow-branded marketing. In the United States, the month of June was officially recognized as Pride Month by the Clinton and Obama administrations. In 2014, the Supreme Court ruled that bans against gay marriage were unconstitutional, and many activists are still working toward full equality, including advocating for protections against employment discrimination and ensuring that all partners receive the same rights and benefits as heterosexual couples. The Stonewall Riots created a huge influx of political and social movement that continues today as activists further the work of organizations, such as the Gay Liberation Front.

Citations

- Bausum, Ann. 2015. Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights. New York: Penguin Group.

- Carter, David. 2004. Stonewall: the Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Segal, Mark. 2019. “And Then I Danced” in The Stonewall Reader. New York: Penguin Classics.

Learn More from Our Collection

Films

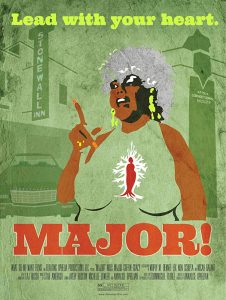

Major! (2015) [Online Access]

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy was a participant in the Stonewall Riots. Today, she is still an active supporter and advocate for transgender rights. She is currently Executive Director Emeritus of the Transgender Gender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project, which helps and supports transgender women of color in prison or formerly incarcerated. The documentary focuses on her work as an activist and challenges faced by the transgender community by the LGBTQIA+ Community and by society as a whole.

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy was a participant in the Stonewall Riots. Today, she is still an active supporter and advocate for transgender rights. She is currently Executive Director Emeritus of the Transgender Gender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project, which helps and supports transgender women of color in prison or formerly incarcerated. The documentary focuses on her work as an activist and challenges faced by the transgender community by the LGBTQIA+ Community and by society as a whole.

Pride Denied: Homonationalism and the Future of Queer Politics (2016) [Online Access]

Pride Denied tells the story of how corporate sponsors coopted the concept of LGBTQ pride, turning it into a feel-good brand and blunting its radical political edge. The film locates the origins of pride in sites of grassroots resistance and revolt, going back to the anti-police Stonewall uprising led by queer and trans people of color in 1969. It then traces how the deeply political roots of pride morphed into the depoliticized big-business spectacles of today — multimillion-dollar events designed to project an image of tolerance and equality rather than calling attention to the relationship between normative identity, power, and sexual repression.

Pride Denied tells the story of how corporate sponsors coopted the concept of LGBTQ pride, turning it into a feel-good brand and blunting its radical political edge. The film locates the origins of pride in sites of grassroots resistance and revolt, going back to the anti-police Stonewall uprising led by queer and trans people of color in 1969. It then traces how the deeply political roots of pride morphed into the depoliticized big-business spectacles of today — multimillion-dollar events designed to project an image of tolerance and equality rather than calling attention to the relationship between normative identity, power, and sexual repression.

Books

Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History by Marc Stein [eBook]

A new addition to the UT Libraries Collection, Marc Stein’s new book retells the story of the Stonewall Riots by presenting over 200 documents relating to the event, including gay-bar guide listings, political fliers, first-person accounts, state court decisions, and song lyrics.

A new addition to the UT Libraries Collection, Marc Stein’s new book retells the story of the Stonewall Riots by presenting over 200 documents relating to the event, including gay-bar guide listings, political fliers, first-person accounts, state court decisions, and song lyrics.

Another new addition to the UT Libraries, the New York Public Library Archives published this book in honor of the 50th Anniversary of Stonewall. Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies photograph and document the LGBTQIA+ activism, protests, and history. Lahsen was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national organization for lesbians, art editor for The Ladder, the organization’s magazine, and involved with the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). Davies worked with the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), the Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries (STAR), and published photographs in magazines such as Come Out! and Gay Power.

Another new addition to the UT Libraries, the New York Public Library Archives published this book in honor of the 50th Anniversary of Stonewall. Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies photograph and document the LGBTQIA+ activism, protests, and history. Lahsen was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national organization for lesbians, art editor for The Ladder, the organization’s magazine, and involved with the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). Davies worked with the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), the Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries (STAR), and published photographs in magazines such as Come Out! and Gay Power.

Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights by Ann Bausum

Bausum provides an overview of the Stonewall Riots and its historical context. The book begins with the events leading up to the police raids and describes its lasting effect on the LGBTQIA+ Community, through the AIDS crisis and into the present-day.

Stonewall: the Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution by David Carter

Carter provides a very detailed historical narrative of the Stonewall Riots, starting with the history of the Greenwich Village and Christopher Street, through the monopoly of the Mafia on gay bars, and the reactions to the events that took place.

Carter provides a very detailed historical narrative of the Stonewall Riots, starting with the history of the Greenwich Village and Christopher Street, through the monopoly of the Mafia on gay bars, and the reactions to the events that took place.