by Mandy Ryan

As library professionals, we often feel that we are working diligently to include and amplify the voices of our BIPOC colleagues. Many major libraries, such as UT and Emory, have incorporated DEI efforts in their hiring practices and Yale Libraries recently posted a position for a Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Organizational Excellence. Publications in the library profession, such as Theological Librarianship and the Journal of the Medical Library Association, made calls for submissions by diverse voices. However, librarians of color often bear the greatest burden in these calls for diversity, which can come with an expectation that they will be the ones to do the work of changing institutionalized practices and management styles built by white supremacy. The lack of effort to examine current processes and prepare staff on how to navigate works addressing diversity, equity and inclusion was most recently highlighted by the editorial decisions at the Journal of the Medical Library Association.

In May of 2020, the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police garnered national attention, generating renewed focus to the Black Lives Matter movement and increased public support for their efforts. On June 1, 2020, the African American Medical Librarians Alliance (AAMLA) Caucus of the Medical Library Association (MLA) released a statement stating that they were “tired of not being seen, heard, included, or appreciated for the value that our unique voices, experiences, and perspectives bring to the narrative” and a commitment to “using our collective voices in bringing about change in the profession and the association.”

In response, the Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) also released a statement of support to both the AAMLA Caucus and Black Lives Matter, stating that they could and will “do more to amplify the voices, experiences, and perspectives of individuals who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).” Part of their statement was a call for manuscript submissions that addressed social injustices, diverse voices, and critical perspectives on health sciences librarianship. They also specifically asked for the contribution of any BIPOC-authored manuscripts, so long as they fell within the scope of the journal.

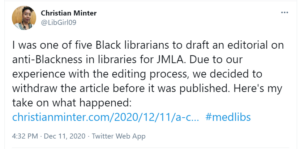

Five prominent Black librarians, Peace Ossom-Williamson, Jamia Williams, Xan Goodman, Christian I.J. Minter, and Ayaba Logan, submitted a proposed editorial on anti-Blackness in libraries. The editorial was accepted and scheduled for publication in January 2021. What happened next became an example of how calls for inclusion can lead to exclusionary and microaggressive practices in editing and publishing. On December 11th, 2020, Christian Minter tweeted about their decision to pull the editorial from publication, with an appropriately titled blog post, “A Case Study in Anti-Black Publishing Practices.”

In the blog, Minter describes how the editing process took a turn when they received a print-ready proof that had significant changes that had not been previously addressed with the authors. Some of the more significant changes she detailed included the decision to capitalize all instances of “white” and “white supremacy,” adding modifiers to “white supremacy” and changing instances to include “white supremacist thinking” or “white supremacist structures,” and changing multiple pronouns from “you” or “they” to “we” and “us.” Originally, the authors had intentionally only capitalized “Black” throughout the piece, but the editor argued that the MLA was in the process of changing their guidelines and that eventually the piece would capitalize “white.” When adding modifiers to “white supremacy,” the editor offered feedback that there was an issue with the literal reading of the original phrase. The editor offered no explanation on why they had changed the pronouns.

The authors attempted to explain to the editor why they had purposely and intentionally made the choices they did for the piece. According to Minter the editor responded by doubling down on her statements and providing a conditional apology if “wording and meaning has been changed that much” and that in her editing for typos, grammar, and clarity, “sometimes it appears the meaning can change.” During the course of the conversation, the editor-in-chief was cc’d on the email exchange, as was an associate editor, but both decided not to intervene.

Minter’s tweet and blog post were immediately followed by a tweet from Peace Ossom-Williamson and a blog post from Jamia Williams, “When Publishing Goes Wrong,” on December 12th. Both authors supported Minter’s account and stated that they stood strong on their decision to withdraw the piece from publication.

The author’s accounts about the events with JMLA began to trend on Twitter, with a call for JMLA to support Black colleagues quickly circulating under hashtags #medlibs, #librarytwitter, and #POCinLIS. Following the backlash, JMLA issued an apology on December 16th, written by editor-in-chief Katherine Akers. In the statement she recognized that she had been cc’d on the emails, but had assumed “that the two parties would come to resolution on their own or that I would be directly contacted by one of the parties if my intervention was needed or desired.” She also acknowledged that the journal was not prepared to edit or publish pieces on diversity, equity, or inclusion and made a promise to make JMLA “a more diverse and inclusive journal with more equitable opportunities for BIPOC authors, reviewers, and editorial board members.”

The original article written by the five authors, “Starting with I: Combating Anti-Blackness in Libraries,” was successfully published by the University of Nebraska Medical Center under the Leon S. McGoogan Health Sciences Library in December of 2020.

The withdrawal and the subsequent apology from JMLA sparked deep conversations about how these calls for diversity and inclusion are often made without the systemic support and structuring needed to actually support BIPOC voices. As part of the discussion, Jasmine L. Clark, Digital Scholarship Librarian at Temple University, wrote a thought-provoking piece, “On JMLA, Conflict, and Failed Diversity Efforts in LIS,” which details organizational justice and cultural competence as they relate to the article and the breakdown of the editing process by JMLA.

There were many points in which the editor-in-chief or the associate editor could have engaged with the authors and ensured that their intentions and voices were protected. The decision to not engage can be representative of a larger, systemic problem of neutrality in libraries where we avoid conflict and confrontation in the workplace, often leading to the harm of our colleagues.

In their responses, all of the authors and Clark found that there was a lack of ownership by Akers of her responsibility to initiate mediation before the situation had reached the point of withdrawing the piece. They point to her role as editor-in-chief and the accompanying responsibility to create an equitable environment that would identify and address challenges that BIPOC might encounter when writing about social justice.

Moving forward, Clark recommends that within the LIS profession “a blend of ongoing DEIA education, organizational/personal assessment, and practiced social skills are required.” She states that concepts of organizational justice and assessment of power structures are often reserved for those in leadership positions, instead of being open to all levels of LIS professionals. She points out that the development of social skills is centered on public service and patrons, instead of how to engage with the colleagues we work with every day.

The events with JMLA are an opportunity to evaluate our own practices and to better equip ourselves in conflict mediation and organizational justice. As a white woman in a field where only 5.3 percent of librarians identified as Black or African American, I hold myself accountable and ask that my fellow white colleagues join me in enacting changes that will allow for diversity and equity, instead of just calling for it and placing that labor on those who respond. Below are some resources and articles that delve into the experience of Black librarians, microaggression in our field, and how we can do better, but I would like to personally recommend reading the original article of the authors in this post as it provides a detailed overview of the history of anti-Blackness in libraries and concrete steps for how to move forward.

Resource Highlights

Books

Articles

- Alabi, Jaena. “Racial Microaggressions in Academic Libraries: Results of a Survey of Minority and Non-Minority Librarians.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship, vol. 41, no. 1, Elsevier Inc, Elsevier BV, 2015, pp. 47–53.

- “‘This Actually Happened’: An Analysis of Librarians’ Responses to a Survey about Racial Microaggressions.” Journal of Library Administration, vol. 55, no. 3, Routledge, 2015, pp. 179–91.

- Dalton, Shamika, et al. “Navigating Law Librarianship While Black: A Week in the Life of a Black Female Law Librarian.” Law Library Journal, vol. 110, no. 3, American Association of Law Libraries, 2018, pp. 429.

- Kendrick, Kaetrena Davis. “The Low Morale Experience of Academic Librarians: A Phenomenological Study.” Journal of Library Administration, vol. 57, no. 8, Routledge, 2017, pp. 846–78.

- Kendrick, Kaetrena Davis, and Ione T. Damasco. “Low Morale in Ethnic and Racial Minority Academic Librarians: An Experiential Study.” Library Trends, vol. 68, no. 2, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019, pp. 174–212.

- Ossom-Williamson, Peace; Williams, Jamia; Goodman, Xan; Minter, Christian I.J.; and Logan, Ayaba, “Starting with I: Combating Anti-Blackness in Libraries” (2020). Journal Articles: Leon S. McGoogan Health Sciences Library. 9.

- Stewart, Brenton, et al. “Racial Climate and Inclusiveness in Academic Libraries: Perceptions of Welcomeness among Black College Students.” The Library Quarterly (Chicago), vol. 89, no. 1, University of Chicago Press, 2019, pp. 16–33.

- Sweeney, Miriam E., and Nicole A. Cooke. “You’re So Sensitive! How LIS Professionals Define and Discuss Microaggressions Online.” The Library Quarterly (Chicago), vol. 88, no. 4, University of Chicago Press, 2018, pp. 375–90.

Podcast

- LibVoices – podcast co-created and co-hosted by Jamia Williams which amplifies the voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color who work in archives and libraries.

Professional Development and Trainings

- We Here – “We Here™️ seeks to provide a safe and supportive community for Black and Indigenous folks, and People of Color (BIPOC) in library and information science (LIS) professions and educational programs, and to recognize, discuss, and intervene in systemic social issues that have plagued these professions both currently and historically.”

- Active Bystander Orientation – “Have you ever witnessed bullying, harassment, or an uncomfortable encounter in a professional context and wished you knew how to intervene? The 2019 DLF Committee on Equity and Inclusion recently put together an Active Bystander Orientation session to help address these questions”

- Conflict Mediation Guidelines – Stanford’s conflict training for the following situations: when you have been asked to mediate a conflict between two people or two groups or when a conflict breaks out between different sub-groups in a discussion.