BEIJING, China – In my last post, I wrote about different awareness campaigns in China, trying to gather elements that these campaigns shared to reach their target audiences. In many (if not all) of the cases, the message was aimed at the general Chinese population and intended to provoke feelings and emotions: love, compassion, concern. But is a message directed towards the general population appealing to people’s feelings the best way to target China’s main consumers of illegal wildlife products?

This week, my colleague Jessica Carrillo and I will be in Beijing interviewing members of environmental organizations that conduct public awareness campaigns in China. Among other things, we are interested in finding out how is it that these organizations select their target audience, develop the campaign itself (how do they select their spokesperson, how do they frame the message, what type of media is used to transmit the message, etc.), and how (if) do they measure the effectiveness of their campaigns. We especially want to know whether there have been attempts to reach men between 20-50 years old, with high educational and economic backgrounds. According to recent surveys and reports, this particular group is the culprit behind the rise in consumption of illegal wildlife products in China.

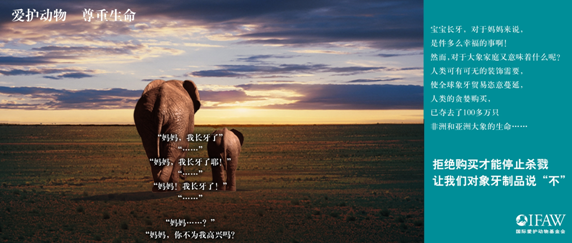

As the crème-de-la-crème of Chinese society, my theory is that this sector might not be as easily moved by IFAW’s campaigns portraying an elephant mother and baby, and similar emotion-driven campaigns. For them, ivory is an investment more appealing than gold—not only due to its monetary value, but also because of its value as a status symbol. Eating salamanders and pangolins, as well as healing their bodies with tiger bone and rhino horn, is part of their identity as important and powerful business leaders and politicians. What would their subordinates think of them if they did not participate in fancy banquets with exotic (i.e. illegal wildlife) meats? Until very recently, their reputations would have likely been jeopardized and their hopes of escalating the business and political ladders might have been at risk (for an interesting study on the world of Chinese “new-rich” read John Osburg’s “Anxious Wealth“).

In this sense, the Xi administration appears to have been more effective than environmental organizations in striking the chords of this entitled group. Instead of trying to persuade their hearts and minds, since 2013 the Chinese leadership has pushed further its anticorruption crackdowns, “incentivizing” these consumers through punishments that might cost them their jobs. These policies mainly aim to curb the lavish lifestyles that high and low party officers (and indirectly, crony businessmen) had begun to get used to. Although the anticorruption campaign addresses a broader range of issues than simply illegal wildlife consumption, since extravagant banquets are on the list of banned activities, hotels and restaurants that used to serve illegal wildlife products have been hardly hit. As a consequence, shark fin soup consumption, for example, has declined.

What if the Xi administration were to expand the list of banned products and decided to include ivory, rhino horn and tiger bone purchases? Would it be an effective demand reduction strategy? How could environmental organizations contribute to increase the pressure on this sector of the Chinese society? What characteristics should campaigns have in order to alter the consumption behavior of this elite? Hopefully our interviews will provide some answers to these questions.

Leave a Reply