Honiara is Solomon Islands’ capital city situated along the Guadalcanal coastline. Much like other island cities in Oceania, Honiara is at risk of natural hazards heightened by climate change. But the stress on Honiara is aggravated since over ⅓ of its residents inhabit vulnerable informal settlements. That means, over ⅓ live on most-likely hazardous lands and lack basic utility services. With a history of colonialism, ethnic conflicts, and governmental malfunction, along with rapid urbanization, Honiara is “living daily with disasters.”

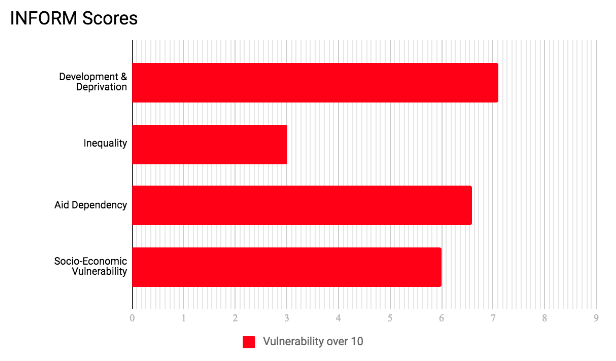

Solomon Islands is part of Melanesia and is a conglomeration of around 1000 mostly-small islands including six major ones: Guadalcanal, Makira, Malaita, Choiseul, Santa Isabel and New Georgia. The country has a tropical climate with rainfall concentrated mostly in November through April. Data from the Index for Risk Management (INFORM) shows that Solomon Islands is particularly vulnerable to earthquakes, tsunamis, and tropical cyclones (figure 1).

Source: Index for Risk Management (INFORM) 2020

The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, also known as Rio+20, which took place in Rio De Janeiro in 2012, recognized that Small Island Developing States (SIDS) have particular characteristics that make them more vulnerable than other states. Specifically, their small size, remoteness, lack of resourcefulness, and high exposure to natural hazards make it harder for these islands to achieve sound sustainable development. The Solomon is one such state. Not only is it particularly vulnerable to climate and geology-driven disasters, it also struggles to recover from its history of colonialism, ethnic conflicts, and weak governmental policies pertaining to disaster risk preparedness, infrastructure, and access to healthcare among other things (figures 2 and 3).

Source: Index for Risk Management (INFORM) 2020

Source: Index for Risk Management (INFORM) 2020

30 thousands years ago, Papuan-speaking settlers inhabited the islands; but it was not until 1886 that Solomon Islands was colonized by Great Britain and Germany who divided the country into two. During World War II, Japan invaded Solomon Islands turning Guadalcanal into one of the most violent scenes the Asia Pacific has ever witnessed. In 1978 the islands gained full independence.

Within the Solomon Islands, big cities have become the go-to destinations for residents wanting better livelihoods. Honiara in particular, is Guadalcanal’s biggest city situated north of the island. It is mostly made up of mountain ranges and rainforests with a lengthy coastline which makes it more vulnerable to storm surges, sea level rises, flooding, and coastal erosion.

However, the biggest catalyst for Honiara’s vulnerability today is the rapid urbanization it is witnessing as a result of rural-urban migration. Said urbanization has strained the city’s already weak infrastructure and made it harder for local authorities to meet new demands of jobs and provide basic services such as proper waste collection and a working sewer system. Rapid urbanization is, however, was not the consequence of migration. Between 1999-2003, the Solomon Islands experienced ethnic conflict caused by tensions between Malaitans migrants who have been migrating to Honiara over the course of decades and original Isatabu landowners who were supported at the time by the Solomon Islands government.

Both sides mobilized to paramilitary organizations; the Malaitan Eagle Force (MEF) and the Isatabu Freedom Movement respectively.

Tensions escalated when 20,000 Malaitans were expelled from the island in 1999. Shortly after that, the MEF established a military police, forced the prime minister to resign, and founded a post office overprinting new Malaitan stamps. A peace agreement was ultimately reached in October 2000 and a peacekeeping force led by Australia fully restored order in 2003. However, because of this conflict, businesses shut down and a large portion of the population was additionally displaced.

Migration and displacement increased the likelihood of establishing informal settlements. In fact, there is a 12% yearly increase in informal settlements in Honiara amid less than an adequate governmental response. As of 2017, around 28,000 people, that is almost 40% of Honiara’s population, reside in informal settlements most of whom are Malaitans.

Informal settlements are especially vulnerable to climate disasters because they are usually located on lands that are unfit for formal development. Clean water ans sanitation is also a big problem in Honiara’s informal settlements. According to Amnesty International:

Informal settlements in Honiara have mushroomed, putting much pressure on infrastructure and services within the city and consequently denying its occupants access to clean water and sanitation. For instance, more than 4,000 people living in four squatter settlements in Honiara have to share piped water from only one broken pipe that is located in the valley in Kobito 1 settlement.6 Those collecting drinking water have to walk up to 1-1.5 kilometers to collect water from the broken pipe twice daily. Each person carried 10-12 bottles of water (of between 1-2.5 liters each and weighing in total 15-20 kilos) back to their households.

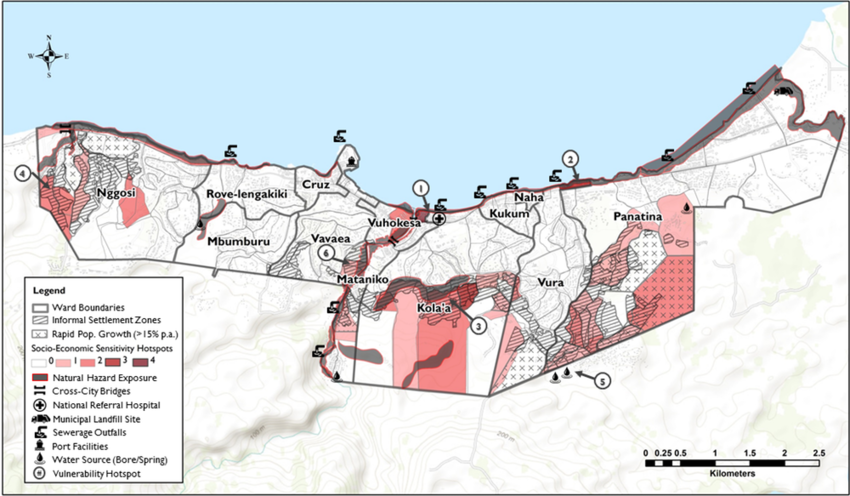

The UN Habitat map below (figure 4) highlights Honiara’s vulnerability hotspots which in most cases overlap with areas where informal settlements have been established.

Source: UN Habitat – Cities and Climate Change Initiative 2014

In turn, rapid urbanization coupled with low governmental capabilities and resources, is adding fuel to the fire. Today, Honiara is the most densely populated area in the Solomon Islands counting 2,953 persons per square kilometer. While the Honiara City Council already administers a wide range of services including education, trade and commerce, youth and transports, and law enforcement, it is unable to resolve housing prices or regularize informal settlements. Given the past ethnic conflict, regularizing informal settlements is hard as customary settlers fear losing claim to the land and all stakeholders fear renewed tensions.

However, to ensure all residents are resilient in the face of climate change and natural disasters, especially in informal settlements, social ethnic controversies and grievances must be addressed. Once addressed, a much wider coordination with all the relevant stakeholders is possible and is likely to yield better results. Currently, the city council is envisaging extending the city’s boundaries; whether or not this will make the residents more resilient or will be a pull factor for more informal settlements and increased vulnerability is yet to be determined.