This blog was updated on 7 March 2020 from its original version.

China’s lending levels and loan-issuing practices are increasingly topics of analysis for governments and policy wonks. Assessing China’s intentions, its massive Marshall Plan-esque foreign development strategy — the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) — and stories of debt trap diplomacy requires an understanding of the international norms, history, and characteristics of lending. This post discusses those aspects and then examines Oceania’s standing as an indebted region.

Historical perspective on Chinese lending:

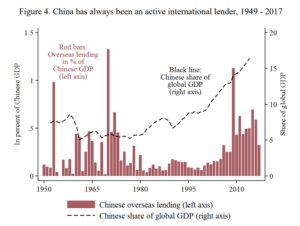

The People’s Republic of China has almost always engaged in international lending. Between its founding in 1949 and the 1970s, China’s lending as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP) ranged widely between 10 and 125%. Such lending is surprising considering China was both an extremely poor and walled-off nation during that period. As is the case with many other nations, China’s lending was geared towards seeking geopolitical interests, namely lending large to fellow communist states.

Recent History:

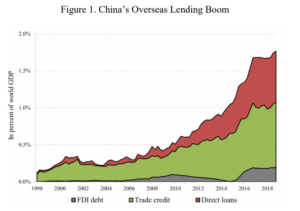

China’s role as an international lender has increased along with its economic might. In the early 2000s, increased lending became an important aspect of China’s “Going Out” policy, which sought broader global engagement. Today, the BRI represents a more substantive “reaching out” policy that relies heavily on development lending on a global scale. Overall, these efforts have seen the number of China’s debtor nations increase to more than 100 (over 150 BRI countries), the majority of which are low-income, developing nations. China now accounts for one quarter of all bank lending to the developing world, making it a bigger lender to that bloc than both the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Chinese Lending Practices Today:

Today, China’s lending stands out not only because of its recent surge in the amount lent, but also because of its unique characteristics compared to most other prominent international creditors. The most obvious difference is that nearly all of China’s lending is official state lending coming directly from state apparatuses such as the Export-Import Bank of China. This is in contrast with lending from other nations and institutions that also utilize private, development, and philanthropic channels for lending.

China’s lending terms are often very different from other creditors. Many international creditors, especially development institutions, offer concessionary lending terms given their altruistic missions. China, however, has been accused internationally of issuing concessionary loans in order to undercut other investors. China accomplishes two things by doing so. First, China secures deals — especially in Africa — that advance its geopolitical aims, namely replacing Western influence. Second, Chinese lending often goes toward massive infrastructure projects that come with requirements to use Chinese supplies and labor; this helps China employ thousands of its own workers and finds a use for some of the excess supply of cement and steel its state-owned enterprises create.

In addition to questions about its concessionary loans, China has also been criticized for issuing loans that use higher risk premiums, shorter maturity periods, and has required collateral clauses for instances of default in their lending deals. The latter has become and issue recently when BRI countries have failed to pay up. Recently, China has started to write off debts and reform lending practices considering many of its partners and prospective partners have voiced their concerns about these practices.

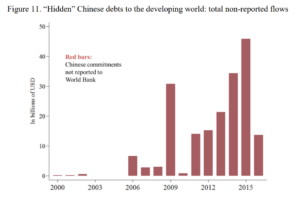

Another divergent characteristic is the opaqueness of Chinese lending. China is not a member of the OECD’s Export Credit Group nor the Paris Club, entities that seek to improve lending practices, coordinate efforts, and improve lending data and transparency. China’s central bank does not publish its bond purchases and recent BRI deals, as well as other bilateral lending, lack public details. Experts at the Kiel institute have developed a methodology to estimate ‘hidden’ debts issued by China. Their analysis estimates that nearly half of China’s lending goes unreported and that hidden debts add up to more than $200 billion. They also report that the phenomenon of hidden loans has drastically increased since 2010.

Analysis and Application to Oceania:

Overall, China’s lending is increasing to a substantial level, it is fundamentally different from other lenders, and it is opaque. These characteristics, combined with China’s rise to great power status, leave many people feeling unsure or uneasy about China’s intentions. On one hand, a growing power is extending its reach to new regions simply because it is now capable of doing so, and it is going about the process in accordance with its ideology and internal practices. On the other hand, that power is lurking behind the scenes, skirting international norms, and making predatory deals that trap partners — all the while collecting strategically significant assets as collateral. Perhaps only time will reveal which interpretation is correct.

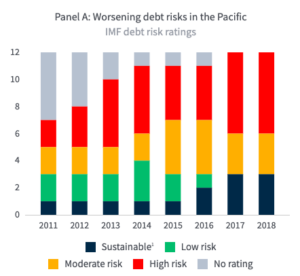

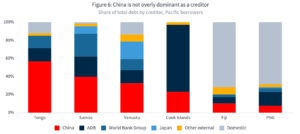

Analyzing Oceania offers little definitive evidence for either argument. In total, six Oceanic states are indebted to China: Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu, the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea. All of them are among China’s top 50 debtors in terms of debt as a percent of GDP. Further, each is an official BRI country, leaving the door for more financing wide open. The Lowy Institute has identified seven other Oceanic states as potential borrowers for China.

A recent analysis of Chinese influence in Oceania concluded it would be unfair to explicitly categorize Chinese lending in the region as ‘debt trap’ diplomacy. A main reason for this conclusion is that debts to China do not make up a dangerous portion of any of the nations’ debt portfolios. However, Lowy experts also found that Chinese lending to the region nearly doubled between 2011 and 2017, and that the sheer amount of those loans and the debtor nations’ ability to handle such levels of debt are problematic. Hardly an acquittal.

Again, it is hard to tell if Chinese lending is predatory or not. In Oceania, making a determination will take time. Will debtors sell more bonds to China? Will China pursue BRI projects in the region? Will skeptical nations look to Australia, the US, and New Zealand instead of China? As my colleagues have pointed out, the region is also important militarily and strategically. Will China try to encroach? Or, as others have pointed out, will foreign involvement — lending, investment, and aid — all help address climate change in a very vulnerable region? For now, your guess is as good as mine.