With nearly sixty percent of total disaster-related deaths — more than two million since 1970 — the Indo-Pacific is the most disaster-prone region in the world. This number should not come as a surprise considering the region’s massive population, the number of people living at or near coastal areas, and the number of developing nations in the Indo-Pacific. Worse yet, the region is becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate-related disasters bolstering growing concern about other threats such as rising sea levels, fishery depletion, and water salination. We needn’t look far for examples: In 2015 and 2016 Cyclones Pam and Winston — the two strongest storms ever recorded in the South Pacific — battered Oceania, a subset of the larger Indo-Pacific comprised of small island developing states (SIDS). More recently, Australia’s intense bushfires provided a reminder that climate change affects more than just small, poor island nations.

The Indo-Pacific’s susceptibility to severe natural and climate disasters makes the efficiency and effectiveness of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) all the more important. International HADR efforts are essential to providing immediate relief to poor, isolated, and/or developing nations in the wake of disasters.

This post strives to outline American HADR in the Indo-Pacific, compare US efforts with China’s growing HADR role, and assess the implications for American and Chinese HADR efforts in the region; in assessing each of these topics, I will extend the conversation to consider the implications for Oceania given the threats facing the low-lying atoll and isolated SIDS in that region. In doing so, this post relies greatly on past work by our partners at the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance, particularly Adrian Duaine and researcher Taylor Tielke.

American HADR

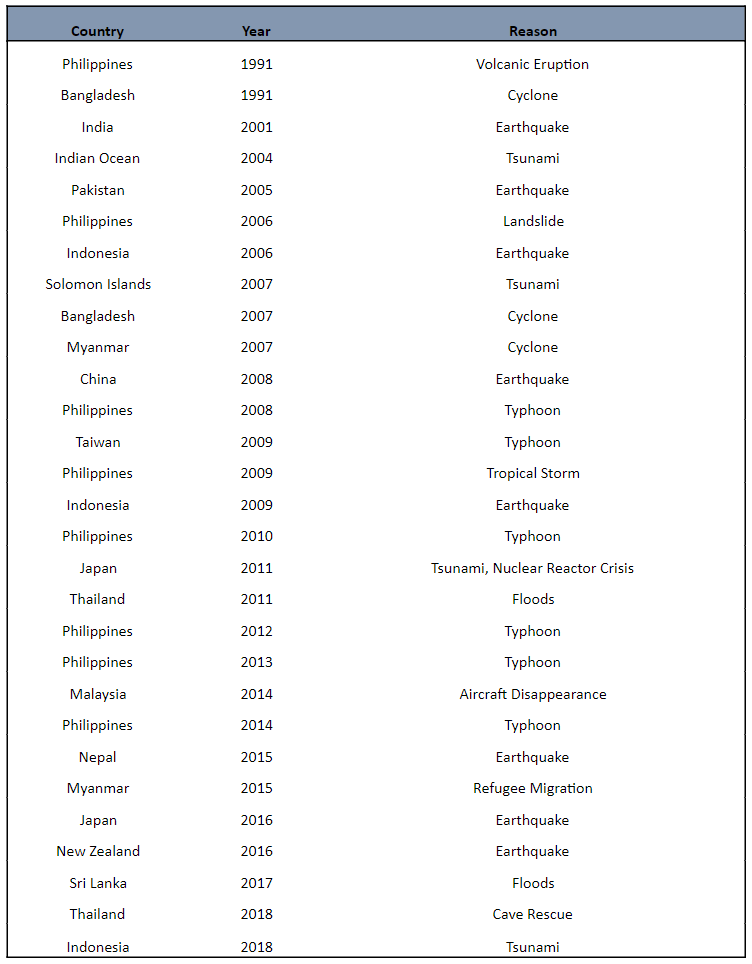

The US has played a dominant leadership role in Asia since the end of World War II. The US’ strong military presence in Asia combines with its inclination to help in times of crisis to make the country one of the most committed and effective international HADR providers. Between 1991 and 2019, the US armed forces responded to 36 natural disasters in 15 countries in the Indo-Pacific region. These interventions include responses to a wide variety of disasters.

US Military Responses to Disasters in the Indo-Pacific: 1991-2019

Created with information from CFE-DM

However, these 36 instances are included in the mere 10% of US global disaster responses that involve the deployment of US military assets. The vast majority of American disaster assistance comes as non-military relief from USAID’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, congressionally appropriated disaster aid, and private and civilian response groups. Again, it is important to underscore how American leadership in HADR in the region stems from available military assets in the region, a willingness to intervene, and a multitude of other American mechanisms that bolster HADR efforts.

Absent from the above list are US military responses to some of today’s most vulnerable Oceanic states and some of the most destructive, recent climate-related disasters. The US Department of Defense’s lone response to a disaster in Oceania came in 2007 when an 8.1 magnitude earthquake struck in the Solomon Islands, displacing over 30,000 people.

Admittedly, the US’ limited number of direct military responses in Oceania is not indicative of a total American absence on the ‘blue continent.’ In fact, the US plays a large role in Oceania in other ways, namely through aid and development assistance. The US has also supported its close allies France, Australia, and New Zealand and their nearly 30-year-old FRANZ Agreement that provides first responder services to natural disasters in Oceania. However, the lone response to the earthquake in the Solomon Islands is indicative of the challenge distance poses to more active US involvement. While the US does have significant military assets in the Oceania, those with the largest number of service members and HADR resources remain on the periphery of Oceania in Guam and the Philippines, making responses to disasters and climate-related events in Tokelau, for instance, very challenging. As it turns out, challenges other than distance are threatening the US’ role in the region.

US Outlook

The importance the US places on retaining its title as the preeminent power in Asia and the Indo-Pacific is well known. However, mounting fiscal challenges and the rise of China threaten its dominant grasp over the region.

Abroad, US military resources around the globe have been strained by drawn out conflicts in the Middle East; this has lessened the US’ ability to have the best equipped, most up-to-date, and forward-facing defense assets in Asia. At home, budgetary concerns quickly followed the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and the subsequent fiscals stimulus. The Budget Control Act of 2011 put caps on defense spending, among other things, further limiting the US’ ability to project power globally. The 2018 National Security Strategy put both words and money behind renewed engagement in Asia. However, the Trump Administration has moved away from the Obama-era diplomatic and economic partnership building ‘pivot to Asia’ instead focusing on an ‘America First’ agenda. Plus, America’s underlying fiscal issues remain unaddressed.

The context underlying all of this is the rise of China as an economic and military power. The American responses to these challenges — renewed freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea, reorganizing their Pacific assets, and a new development financing institution show geostrategic, military, and economic competition with China tops the US’ list of priorities — not addressing climate change or improving HADR.

Overall, the US still holds its strong military position, and HADR capabilities as a result, in the Indo-Pacific region. However, there are serious threats to both, and China is catching up.

Chinese HADR

There are two key challenges to gaining an understanding of China’s HADR efforts. First, Chinese HADR is opaque. China, not known for its transparency, can be extra secretive regarding HADR for two reasons. The CCP’s legitimacy and maintenance of internal stability have been threatened not only by disasters themselves, but also through public criticism of the government’s responses. The latter can be worsened if international or multilateral HADR teams enter China and provide better relief services than the People’s Liberation Army. China had issues on both of these fronts and blocked criticism from citizens and made it tougher for international organizations to enter the country after a deadly earthquake hit Sichuan province in 2013.

So, what does the lack of transparency mean? Today, the ongoing Coronavirus outbreak provides an answer. The lack of transparency internally and internationally negatively affected the Chinese response to the outbreak. Health experts have pointed out that the CCP’s secrecy — the layers to who knew what and when, and the decisions to silence whistle-blowers — is what allowed the virus to become a global pandemic in the first place. The conclusion here is that some of China’s domestic practices are incongruent, perhaps even antithetical, with providing effective, efficient HADR domestically or internationally.

China’s Increased Role

The second challenge to fully understanding China’s HADR efforts is the fact the country’s efforts are new, and there is a small sample size from which we can extrapolate. As we will see, some have concerns about China’s HADR intentions and level of commitment even though China has put forward a concerted effort to increase its HADR role.

In 2004, Hu Jintao, general secretary from 2002 to 2012, made the case that China’s role in international HADR efforts was part of a broader ‘historical mission’ on which China would increase its global role. Along with other international commitments to helping fight terrorism, transnational crime, and other global problems, Jintao signaled China would, as part of its ‘going out’ policy, take seriously its responsibility to help in the aftermath of disasters. Since then, the PLA has provided HADR in 16 instances in 13 Asian countries.

Chinese HADR Responses Abroad 2002-2019

Created with information from CFE-DM

To do so, China has built up its Medical Rescue of China International Search & Rescue Team (CISAR). As an example of CISAR’s capabilities, it deployed a 68-member team in the aftermath of the 2015 Nepal earthquake. In two weeks of work, the team treated hundreds of victims and helped clear damage. Another example of China’s commitment to HADR is their deployment of Peace Arks, two hospital ships christened in 2008 and 2019, specifically for international emergencies. With regards to Oceania, the Peace Arks have made voyages to Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Fiji, and Tonga since 2019.

China’s Peace Ark at Sea

To further these efforts, China recently created a digital application to facilitate better emergency data from disaster zones. Furthermore, while information and numbers vary drastically, it is clear China has also committed several hundred million dollars to non-military relief efforts in the region as well.

Overall, the Chinese appear to have used the ‘historical mission’ approach to drastically increase their regional presence and HADR efforts in the region. This of course was afforded by China’s rise as an both an economic power and a military power with the assets capable of providing HADR.

To what extent China will remain committed to HADR efforts in the Indo-Pacific remains unclear. While I have provided the case that China has stepped up its efforts, other examples show a paltry response that clouds what we can definitively ascertain. For example, China pledged just $161 thousand to Ebola-affected countries in 2014, compared to the hundreds of millions donated by other global powers. China upped its pledge to $120 million and sent more than health workers to the region under intense international scrutiny of their initial commitments. What does this tell us? Perhaps China does not care about international HADR, or perhaps just not outside of its neighborhood. Only time will tell.

HADR Cooperation Going Forward to Benefit Oceania?

What are the prospects for US-China HADR cooperation and collaboration going forward? Some evidence of HADR cooperation exists, showing that the US and China can collaborate amid bilateral tensions. However, those instances of cooperation are too small and too infrequent to suggest a more meaningful partnership will blossom. Plus, institutions of the US government have recently voiced the concern that the Chinese have used military-military exercises to spy on America’s tactics and capabilities.

One potentially tenable path for HADR cooperation might be through the two countries’ shared presence in existing Oceanic multilateral organizations, namely the Pacific Islands Forum and its 2016 frameworks for Pacific Regionalism and Resilient Development.

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) is the main multilateral body in Oceania; it was created in 1971, is based out of Fiji, and its membership includes 16 island-nation members plus Australia and New Zealand. The Forum has 18 dialogue partners, including the US and China, to help advance its broad agenda. The Forum though, has not lived up to its potential. In years past, efforts on climate change and economic development have been stifled by Australia throwing its weight to block meaningful climate action and outside donor countries (not limited to active dialogue partners) pushing the economic agenda in ways that do not address SIDS wants and needs.

SIDS nations in Oceania have addressed those issues by creating sub-PIF fora through which their voices and perspectives can resonate. The 2013 Pacific Islands Development Forum and the Smaller Islands States groups are comprised of the most vulnerable countries in Oceania. These two sub-organizations have afforded SIDS the opportunity to voice their concerns and needs on both developing a ‘blue’ economy in a ‘green’ way and HADR/climate capacity building.

To do so, the Framework for Pacific Regionalism establishes the methods and procedures through which PIF countries can improve their coordination on legal, governance, financial, and administrative matters. Building on that, the Framework for Resilient Development identifies low-carbon development, adaptation/resilience improvements, and HADR capacity building as goals while also providing actions, processes and monitoring and evaluation methods to achieve those goals.

What does the recent reorganization and action by PIF and its offshoots tell us? Two things. First, that SIDS are breaking free from the influence of outside powers pushing agendas asymmetric to the needs of vulnerable Oceanic states. Second, that those very countries are making a concerted effort to etch out their own path and make their collective voice heard.

What implications does this have for American and Chinese HADR and other involvement in the region? The transformation of PIF shows that unwelcome influence is becoming less and less tolerable to those states with the most to lose. While it remains to be seen if smaller countries can afford to kick an Australia out of PIF or reject Saudi money, the efforts to route around unproductive ‘partners’ is clear. As a result, SIDS in Oceania are likely to have a louder voice that makes clear what they seek from outside dialogue partners and great powers like the US and China.

In terms of requesting certain actions from partners, Oceania making more specific HADR ‘asks’ might run counter to the status quo of the US and China being involved in ways beneficial to their geostrategic aims, or when/where is cost effective for them. For China, this might mean Belt and Road investments need to become overtly sustainable and geared towards resilience building. Loans might need to be made in more transparent, reassuring ways. The Peace Arks should be on call for the next disaster, not parading port to port like the Great White Fleet.

The same lessons apply to the US side. The new BUILD Act and Development Finance Corporation should not simply seek to compete economically with China, but to invest in meaningful ways that enhance countries’ resilience capacities or domestic HADR resources.The sole incursion to the Solomon Islands cannot be seen as the boundary for how far the US will venture into Oceania on a HADR mission. The threat of not making these adjustments is opening a door for a geostrategic competitor to step further into the region and make friends.

Overall, the outside power(s) that recognize Oceania’s increasing vulnerability, SIDS’ consolidated voice, and choose to pay attention to the specific HADR needs in the region stand to gain not only by securing allies and competing for allies — but by doing what is right.