Patricia A. Wilson

Patricia A. Wilson

Professor, the University of Texas at Austin,

Graduate Program in Community and Regional Planning.

What has been your experience working in informal settlements?

Over the last three decades, I have been working in informal settlements mostly in Latin

America and also in Africa and India. Examples of that work are in my new book called “The heart of community engagement. Practitioners stories across the globe.” So there you would see stories from El Salvador, Colombia, Mexico, colonia de Las Lomas -a rural area of Texas near the border with Mexico, rural India, and few others.

When will this book be available for the audience?

The big date is July 2nd, 2019.

How did you initiate your collaboration with a community? What are your most effective strategies?

In my experience, there have been several ways of how I started a relationship with the community. Sometimes comes through another practitioner who already has an established relationship and I go with them and get to know the community in that way. Generally, there are some intermediary organizations respected in the area, that provides the contact locally. Those contact points turn out to be pivotal in creating trust and openness to talking with my group of students from the University of Texas at Austin and me. That is the first step having a relationship to start with that introduce you to the community.

A great example of this was the very last one, in Monterrey, Mexico. That collaboration started with a non-profit organization that works there. The beauty of that relationship is the beauty of that organization’s philosophy of being very participatory in the approach to local informal community. So we saw eye to eye both agreed on that. I notice that Celina, the director of this local NGO -Barrio Esperanza- was worried of outsiders, especially universities, faculties and students getting involved because of some prior experiences that people would come in with the answers instead of coming with an open mind, open ears, and open hearths. I think, she was very relieved to find that we were coming with an open mind, open ears, and open hearths, and that’s how we were able to build a relationship of trust with her, and the work with her at side by side in engaging parts of the community that she not engaged before.

How did you plan your withdrawal? What have been the challenges associated with “leaving”?

The quick-in and the quick-out is the kind of approach that I don’t like. I like to build a long relationship with the community. So for example, in the two communities through I worked outside of Mexico City, two peri-urban informal communities, that relationship lasted for seven years. I went back every year, so they knew us, we knew them, and while different students I was bringing each time there was still a sense of continuity which created depth.

In some cases, it’s not known whether would be a follow-up opportunity, but I like to leave the door open to that and go with the longer term view in mind because that is what influences your ability to build a relationship and prevent a more instrumental, utilitarian, use of the opportunity. Thinking about the long term is useful even in the short term to decide what is it that is wanting to happen here. What is it that was being called to do there? How is it going partner locally? We require a long term view to understand what it is needed, and a long term views towards maintaining and cultivating a deeper relationship.

I remember one of our first sessions in the course, and you reflect on this analogy of “jump rope,” could you please share with us your thoughts again?

This analogy is very important and key I think to have the right attitude for engaging a community. If you can picture the jump rope going around with a person at each end and just draw an analogy in your mind, the moving jump rope is like the moving, changing system of the community that you are entering, how you enter a moving jump rope? I have seen people doing all kinds of things for entering in a moving jump rope, from telling people to STOP, “stop turning the rope let me get in there, and I’ll tell you when you start turning.” That is an example of imposing one’s own will on the community and not paying attention, then not respecting what it is happening in the community. The more agile way of entering a community is to stand and observe, listen, and look, then you perceive the rhythm of the rope coming around, the length and where the rope is hitting, you see the people and whether are excited or tired turning the rope, you get the sense of what is happening and as you begin to get that sense you enter into the jump rope in unison with that rhythm.

And you can be stressed by or enjoy the rhythm …

Exactly. And if you make a mistake, don’t worry. That is even in your benefit in how you handle it. If you laugh and realize the ridiculous how you look because you goof off and you step on the jump rope, then people see you as human, you are able to laugh at yourself, and so that’s good too, but they saw you get intended to get into their rhythm, that you tried your best, you are not trying to look superior, and you are just learning and willing to show yourself.

Thank you. So let’s talk about the role of UT in your work thus far… Have there been changes in the attitude of the university towards this type of work? How do you envision future collaborations? Are there changes you would like to see regarding the university’s role?

The presence of the Institute of the Latin American Studies and its reputations for being known as a major center of Latin American Studies with the finest library possible in the hemisphere was a major attraction to me when I accepted the offer of the University of Texas. LAS even sweeten the deal to make it very attractive to me to come to UT because they are interested in Latin Americanist to come in, even though I was coming into a community on Regional Planning, on the opposite side of campus, they really wanted to grow the Latin Americanist faculty on campus and they are very well known in that. So it was a crucial attribute for me to come here. Then, as a young assistant professor, it was very meaningful to me to get this support and the coaching from the leadership in Latin American Studies, I was getting mentorship from them about how things were done atUT and how an Assistant Professor could handle herself at UT. So that kind of collaboration that doesn’t have the pitfalls that somebody in your very milieu in your department may have. That support was valuable.

Then, of course, the research funding that I obtained through the Institute of Latin American Studies was very crucial for me as an Assistant professor getting my fieldwork going. I specialized in Peru and Chile, and throughout ILAS I was able to get grants to go to Mexico, and places that I wasn’t an experienced researcher in, so that helps me spread my wings more broadly in Latin America. Also, through on-campus activities on Latin American Studies, I met scholars from throughout the atmosphere Latin Americanist, and that was valuable. It was very important to me be connected with LAS as a non-professor, and over time I could always call on LAS for support of many different kinds, my research, my teaching, getting good students from other departments who are Latin American students to take my courses and to have a broad set of colleges to work with.

How did the collaborations with those colleges have to be and how do you envision the collaboration with them?

Well, I remembered one such collaboration that was something that never has come my way by on my own, that was to work in Nicaragua during the Sandinista government. Of course, this variants collaboration opened up writing and publishing opportunities. I also got involved in governance in LAS being in the faculty governance committee. How did this collaborations change over time? Different directors of ILAS have had different interest, and I thrived most when they have had an interest in social science, but in large ILAS directors, regardless their particular specialties learned to bring together multidisciplinary groups so that’s been an assets during the years, so faculties, administrations, and students, especially when I do fieldwork courses to find to get critical mass of students who speak Spanish and have prior fieldwork it is a wonderful asset that really deepens the tenure of the field project.

Many of these communities have experienced violence, displacement, invasion, disruption, etc. After these traumatic experiences, how do you work “repairing” the damage done to the social fabrics? (Is part of your/our work as students/ut role?)

It is impossible not to be aware of the damage to the social fabric. After the violence in Peru, where I had worked for many years including doing my dissertation fieldwork there, when Sendero Luminoso was powerful and threat where even in the urban areas in Lima it was very difficult to teach classes there and research and while Peru was my most beloved country of Latin America for many years I had to pull out of there because of the threat to safety for students and myself. That was sad; it was a couple of decades before I returned to Peru.

The most recent example in la Campana, in Monterrey, Mexico, that is a community that was not very long ago torn by the drug cartel wars, and of course it takes a long time for social cohesion and trust to rebuild, and it took quite a while in our last field project to get to the point where the community members were willing to talk about that because it is so personal so tender, but they did, we reach that level of confianza o confidence to be able to talk about that and to keep that always in mind that there is a background of violence fear and oppression, and incredibly difficult challenges. It is very important. There is another time in an informal community outside of Mexico city where they were very excited to tell me about their new venture=1942 it took as a long walk to this pristine valley, and they were delighted to show us the new land they were settling, and it was obvious that this was a land take over, and there was trust in a difficult situation and again I had to withdraw because that was a volute situation and the primary concern was students safety, so we were)=drew=2019 even though we were worked with that community for several years before they attempted the land take over.

How do you perceive the responses of students to these challenging situations?

Well, students have a life change experiences doing this field projects because whatever other they created in their minds breaks down and when they feel accepted by others and accept them is a feeling of a indescribable satisfaction that motives many of my students to continue on in that line of work of in community engagement, community development. So it is a very heartwarming response, and also it is eye-opening to really understand situations that people are facing, and it is very humbling to know how little you can really do to help, but the main thing is you also get to see how you can provide support and collaboration to what they are doing.

Thank you so much for your time and your answers Professor Wilson.

Bjørn Sletto

Bjørn Sletto

Associate Professor

Graduate Adviser for Community & Regional Planning

What has been your experience working in informal settlements? Where have you worked and what sort of projects?

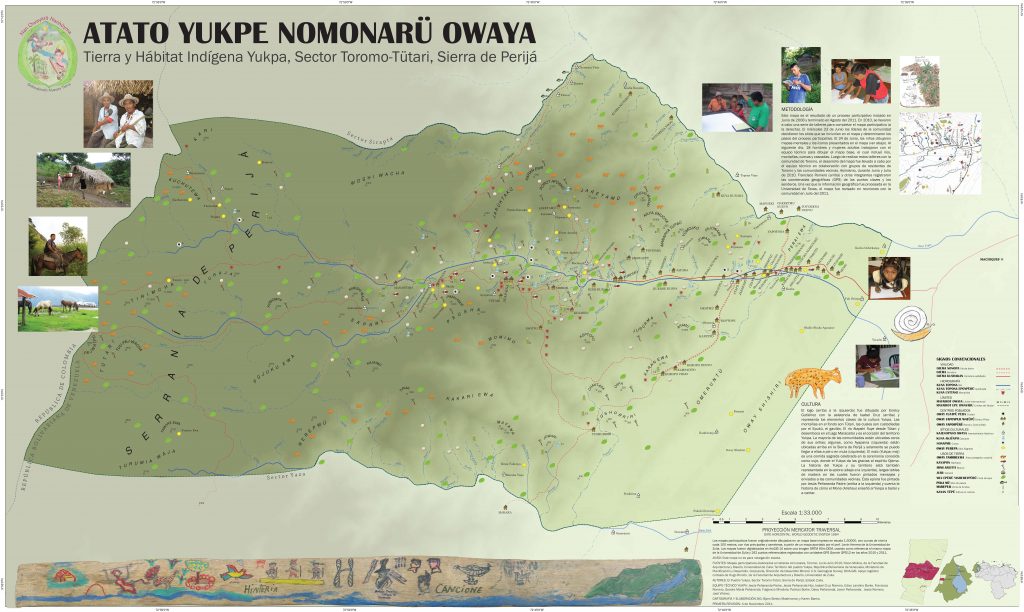

Should we include indigenous communities? So I think, we can start with the work in Venezuela. In the indigenous communities among the Pemon, in eastern Venezuela.

That work was focused on indigenous territoriality, meaning I wanted to participate, be an alley, in their struggle to obtain rights to their original lands. The specific work I did was to help codesign and lead a participatory mapping project. Figuring out ways in which we can sort of democratically and nonviolently as possible transform this mental knowledge these memories into something that can be represented on paper. So, in other words, the map you see on the wall, behind you, never existed before. Nobody ever used a map among the Yukpa. Spatial knowledge was always transmitted orally and learned through walking and hunting and experiencing the places. The point is for the map to be rhetorically powerful and have it appear to have scientific validity so it can carry weight in the negotiations with policymakers. So that’s what I was doing there.

In some ways the work I did afterward with my students -in 2008, in an informal settlement in Santo Domingo- in Los Platanitos is this process of transforming, with all the problems and challenges that it entails, transforming these memories and experiential knowledge and perceptions and values that people have but have not articulated in writing.

The point has been to transform the knowledge into a form or representation that might carry some weight politically. So, in other words, you have to know what sort of information residents want to communicate. We had the parameters from the law, from the constitution that said “you have to document your sacred sites, and your land use areas” okay so we had a starting point and we know the end goal, a map that we could use for negotiating land rights claims.

So, what they want to communicate has been difficult and I think it has shifted over time, as new realities have emerged. A lot of it has been sort of communicative. That’s a theme that comes up as I talk through this. It’s about communicating historical uses and occupations and meanings of the land of indigenous people similarly a little bit in LP documenting the space and how they want it to improve. And us serving as this role of ally, translator, communicator.

What have been your most effective strategies doing that, doing your work in these communities?

I think it has to do with making connections with people. I spend a lot of time just sort of developing relationships without pushing. Without, trying to not be the anxious scholar that I am. I try to sort of taking it easy, listen and be present and patience. All those sorts of techniques for establishing rapport, so you get to a point where people really share their opinions, really share what they want from you. And actually, critique, criticize you or explain to you if you are doing something wrong. And I think that is a weird challenge for someone who is in such a position of power as a white male in a place like this where there is sort of an automatic difference and suspicion. It’s a weird sense of being polite and sort of differential and at the same time like “I don’t trust this white dude”. That type of skepticism is totally understandable, given the history of these places. And if you don’t sort of deal with those issues of positionality and who you represent you are just not going to forge the relationships or trust that are necessary.

How did you plan your withdrawal? What have been the challenges associated with leaving?

I totally know what you are talking about. I have not had to withdraw from Los Platanitos yet. I don’t really have a strategy to withdraw, my strategy is to not withdrawal from Los Platanitos but maybe withdrawal means to slow down so maybe ease up a bit. And I think my strategy is to do my own visits. Like this summer I am going to bring 3 students because I have 3 grants left. One of them has established relationships there but I’m not going to abandon them. In the case of Venezuela, there was a period of 2 years where I withdrew slowly by visiting less frequently. This was the case on both projects, there was a clear agreement in writing as to what I was supposed to contribute. So there was a contract established with the chiefs and the big project was to produce this map. There was no statement about what I was going to do following that.

Many of these communities have experienced violence, displacement, invasion, disruption, etc. After these traumatic experiences, how do you work “repairing” the damage done to the social fabrics? (Is part of your/our work as students/ut role?)

In Los Platanitos, Dominican Republic, it was a stable situation and then the displacement happened, and I don’t know, I never had to prepare for anything like that with students. I guess I just followed the same strategies as before, just preparing the best I could in the classroom, talking through all the possible challenges, and hopefully having the opportunity in the field for people to talk and listen to people. I didn’t know what else to do, you know? It was difficult. It would have been different if it was, for instance, a brand new community, like let’s say I somehow had taken on a project in a place I didn’t know…then my thinking would have been very different because then I wouldn’t have had the confidence that you would be received well. I had my relationships with people, so I sort of knew what to expect; it was terrible but I sort of understood that people felt comfortable enough with me in the community, you know? That made it more feasible to do, but it’s really hard. I think to bring a class into a place like Los Platanitos, I would not have done it if I didn’t have that relationship. I would have felt, “I don’t know these people, they don’t know me. I can’t do this.” But people in Los Platanitos were waiting for me… it was even more important to manage expectations because of this severe disruption… it’s not just difficult from the perspective of community members because frankly I think after 10 years what we can and can’t do, they are pretty well trained. They know what they can look forward to and what they can expect. But that’s under normal circumstances and now there are very different circumstances. They are particularly vulnerable to the point of desperation, more fragile than usual. Before they were vulnerable, but they had figured it out in a way they were uprooted, disrupted.

Have there been changes in the attitude of the university towards this type of work? How do you envision future collaborations? Are there changes you would like to see regarding the university’s role?

They feel that the university doesn’t appreciate it enough how time-consuming and emotionally draining it is to do these kinds of collaborative work working with communities. And that is pretty much generally true. I talk to a lot of professors about this kind of work.

Higher academia in the US is structured so that you have to publish to survive, publish or perish. When you do this type of engaged scholarship with students it leaves very little time in the day to write. So that’s just the very pragmatic part of it.

Institutions would need to provide relief in one way or another for faculty members, like course release or some time off so you could do this while still publishing. Basically, providing the time for a faculty member to succeed. A lot of faculty members will tell you they just haven’t done this kind of work because they can’t because they are afraid that there is not going to be enough time left for them to publish, so they aren’t going to get tenure.

I think there is some time lip service paid to engaged scholarship or working with communities and diversity. I think there is a lot of rhetoric around that at the highest level of universities, and I think that is not often followed up with actual resources. I think the University of Texas has gotten much better at sort of providing resources, funding, supporting faculty lines with some course buy-out. I think it’s getting better now in recent years.

The international is even more difficult because you have more challenges in terms of preparing students and in terms of dealing with cultural challenges, language problems, homesickness, all sorts of things that can happen when you have students abroad. The paperwork is out of control!

On the one hand, you have the expressed vision of the university to foster international collaboration and student engagement and on the other hand, you have the administrative reality. It’s not a smooth process to do this.

Gabriel Díaz Montemayor

Gabriel Díaz Montemayor

Assistant Professor

Graduate adviser for Landscape Architecture

The first part of this interview is the transcription of the conversation that Gabriel Diaz had with the students in the studio to share his views of the project in La Campana and his professional experience in Mexico, especially in Monterrey.

What has been your experience working in informal settlements?

All my experience in participatory processes is in the North of Mexico.

One of the critical problem in the implementation of infrastructure of public investments, public space, public service, is the strong tradition of a top-down approach which is very difficult to shake off even when particularly in larger cities, probably not the same in smaller towns. Also, there are efforts in almost every large city to revert that in a more community-oriented process, I think is not sufficiently enforced. There is still a lot going on with top-down processes wish do not care about the opinion of the people and do not make people become part of the project.

One example, a most recent project that I designed with my firm in Mexico wish was commissioned to us to design a park. It was commissioned to us by the Municipal Planning Institute of the city, which had been making efforts in participatory planning yet when it came to delivering the project as public space it was disassociated that planning with the implementation of the design.

When we got the commission, we went to the site, and we realize that it was not just dirt right away, was a one mile long, 40 meters wide, which was planned to be a part of what was the weekend market place in this community. It was a very low-income community in the city of Chihuahua, Mexico. Nobody told that information. I think the municipal planning institute they even not knew.

We decided to do a participatory process to design, to produce the program to identify what was the people’s needs and then eventually establish the program of the park and it was implemented, I think successfully. It was successfully implemented because we kept the market going on, but we deliver specific program a service that otherwise was not given to us.

The problem I see in that, this is a progressive city like many other cities, and I would argue that this is also one of those cases of Latin American cities that I get to know that the planning is very aspirational, but the reality is very different.

We realize that we get lucky with this project because we fall in love with it. It was shelved for three years, and then another Mayor came into office and decided to build it. This mayor had much more focused social agenda than the previous one, which is demonstrated how the commission was given to us. I’m sure if any other firm not all other firms in the city, but I know quite several firms, because the low fees that you get to charge assigned in Mexico, they would go ahead and design whatever they want to design. They don’t care what is going there. Turn out of the park as rapidly as possible and do not have problems anymore. I don’t blame them at all. You ended up sacrificing a lot, and your fees are minimal. So, in another word, we lost money. But it was worth it; we had the luxury to do it.

The other example is a project for the United States for Aid and Development, USAID, to be the general consultant in a public space and neighborhood recovery project which was piloting a project intersecting three methodologies. One was crime prevention through environmental design, which is more spatially oriented. The other one was attention to youth at risk of becoming victims or perpetrators of violence and crime. The last area was the prevention of gender-based violence.

One was in Chihuahua city, my hometown, and the other one was in Guadalupe, in the metropolitan area of Monterrey. In Monterrey both local governments in collaboration with USAID selected this neighborhood to try to implement this pilot project which intersected social interventions with physical spatial interventions, right? I am more a designer more than a planner or community organizer, but USAID had an impetus to explore this relationship (social, spatial interventions) It was all understood as an experiment, a pilot project. So, we work on that for a year and a half, 18 months.

The neighborhood in Chiguagua, I think was a successful implementation. But the one in Monterrey Metro in Guadalupe was a failure.

There are multiple reasons for that. One was the political environment; the political trust about the implementation of the project in Chiguagua was stronger than in Guadalupe. The mayors have a lot of power on how they tell everyone else within their power to focus their efforts. Then the Mayor in Guadalupe was not convinced about this kind of projects like this one.

Another tangential reason was that the mayor in Guadalupe was not seeking reelection on the contrary to the mayor of Chihuahua. And these neighborhoods are in very populated areas so, in other words, one mayor was seeking the votes the other one was not. That was an apparent reason.

Now, thinking about the space, the neighborhood in Chihuahua is an island at least two miles away from the closest urban area. An isolated neighborhood, which often happens in Mexico by the first twelve years of the century. Millions of subsidized homes were built in the country but outline areas far away from work, commerce, service centers, because that was the equation that profit makes sense: cheap land far away, nobody cares who is going to live there. I believe that many of these large developments make people poorer. Many of these subdivisions have a high abandonment rate. For example, in Juarez which there are 50% of abandonment. In this neighborhood, it was 30%, which is a lot. Three of every ten houses are abandoned, not empty, abandoned.

So, in spatial terms, the Chiguagua neighborhood was much more identifiable unit. People from there refers to Chiguagua as another city, like “yea, sometimes we go to Chiguagua.” Particularly for the kids, teenagers, the youth who were pretty much captive in the neighborhood. On the contrary, the adults, because they must work in the city.

In Guadalupe, in contrast, is already within an urbanized area but the problem there was that the definition of the area under study, the spatial definition of the community, was an arbitrary polygon which was determined by one factor only, which was violence and crime incidents. But they didn’t take into consideration the fact that every time we have drawn a line into the community is an arbitrary act. But you must do it, right?

Unfortunately, that polygon was divided into two halves. One half was a neighborhood of low to very low income and social, economic conditions. The other half, divided by the park, was a median-low income neighborhood. So, these two different social strata put together into the same bag were asked to cooperate and think about themselves as one community. (So, you have some people not willing to be invaded with others.) The first argument was to blame to the low-income side about violence and crime. So, the troubles arise about robberies, or like that. So it was impossible to think that as a community.

In my opinion and my area of expertise, the spatial thing is essential, and this was a mistake. We need to be very careful about how we decide on the spatial definition and where is the community. The community concept is dynamic. Also, there is one community at night another during the weekdays or weekends. Some flows are more complicated than that.

At the end of the USAID project, we did a final document. So, my job was to put together what has well documented the problem that was to them. That was a problem. We didn’t have a community to work with

Many of these communities have experienced violence, displacement, invasion, disruption, etc. After these traumatic experiences, how do you work “repairing” the damage done to the social fabrics? (Is part of your/our work as students/UT role?)

Well, we did not do with students, but it was part of the work repairing that damage. In the USAID project one of the perspectives implemented was the prevention of the gender-based violence, which we knew very well through our baseline studies that the most critical gender-based violence was happening in that particular context was domestic violence and most of that violence was male partners husbands, been violent with their partners, sons, and daughters. That was a very pointed problem. Even in the period of the romantic relationship is a normalized situation that girlfriends are subjects of violence by boyfriends. In Mexico, the statistics that we work with were telling us that 50% of women in Mexico have had some form of domestic or teen relationship violence in their lifetime. So is a common situation, which was one of the things we were trying to tell the people through the engagement of government entities address the problem and NGOs through workshops and theater shows in which we were trying to say that this is not normal. We were also open in our series of seminars to had some representative of different entities that take care of the victims of domestic violence. So, we tried women felt encouraged to use the resources available that we have for them. Most of the time this was goes silenced; people do not speak up. We try to raise awareness and offer the help that exists closer to the people.

The other issue was the attention of youth in risk. We design a program to identify those teenagers that were most likely to become victims or perpetrators of violence. What we did is to establish processes, protocols, and workshops in which specialized consultants of NGOs interviewed youths to identified if they followed the indicators of being prone to violence. According to our baseline studies, we knew that violence has a high impact in the community even though it is a small percentage of the population that executes violence. Our task was to identify who were those so we could engage them within programs. In over 90% of the cases are males involved in violence. In many cases they are not attending school they drop off, so these programs aim to get them back to school, reinserted or to get them employed. To help them to develop skills.

How was received the help of USAID project, thinking about the history, stereotypes, and prejudices of the support coming from the US?

This is important because USAID was just technical support of the local government. It was not USAID doing the project. It was an agreement between USAID and the local municipal government to implement this project. So, the consultants and I on the ground we were paid as technical support by the USAID, but this was a local government project. We were there and did mention USAID, but in the public events that we held, the logos was the local government who invited. It was not a secret that USAID supported this, both mayors during the program did mention this in public meetings. When we used the USAID logo was in the context of our meetings with the municipal government and the NGOs that we were working together, not with the community but that was part of our structural work. I honestly think that a lot of people do not understand what USAID means. So, either was something probably more obvious, maybe it would be a different reception, but that was not the case. From the community, we did not receive any opinion in this matter.

What has been the role of UT in your work thus far? Have there been changes in the attitude of the university towards this type of work? How do you envision future collaborations? Are there changes you would like to see regarding the university’s role?

I think that UT is very supportive of this kind of endeavors. Maybe we need to work more in the School of Architecture in recognition of the important role of a socially oriented construction of the design. I mean that we should probably do more work to associate the idea of the design for and with communities. In that regard, I am in total agreement with the acceptance of this in the planning world, including myself. We must do work in the design realm towards the recognition and integration of this into how we design. There is still a primacy of the authorship idea. I am not saying it shouldn’t be space for architectural authorship just saying that the design for and with communities approach is something that is going on, it’s not an isolated idea. To me, that is an obvious way to farther link the sophistication of planning at the social, economic, and environmental precision and awareness of planning into the design. Be more responsive to the social criticality of design.

Let me put in this way; the authorship is fantastic to have it but also a responsibility for us as designers to understand that that particular approach has failed in many instances, it is not to serve the broader community, we need to find ways to maximize our impact as professionals. And the way to do it strengthens our methods, technics, and also compassion to work with communities.

How did you plan your withdrawal? What have been the challenges associated with “leaving”?

In my work in Chihuahua, for example, we had very clear parameters. We deliver and now is a public space, that’s it. In the USAID project case, all idea was about developing a pilot methodology and make it institutional leaving the technical capacity in the local government to continue to implement. It was successful in one of the cities that is still going on. We left one year ago the consultancy on the ground, and they are still working on with the public officer that we tried in the methodology and they are still making the project happened. Now, I know from anecdotal experience that for my college that was on the ground, who was the person that initiated all thing, it was difficult for her to withdraw because she has the mystic she becomes emotionally attached to a lot of people she met, but it was no longer part of her job, her consultancy stopped. She had hundreds of WhatsApp contacts in her cellphone asking her things about the project, letting her know about the success or failures, so that was difficult. I guess that must happen, right?

There was somebody left in her position a municipal government employee and that person too as well as the other neighborhood manager were hired, they were identified with our help. We told the municipality a profile of person needed. I think we did a very good job doing that. So, at this point, seven months we left, I know the project is still going. One of the things that happened was that the methodology was included in the municipal development plan, as part of the strategies, the problem is that every new municipal government puts together a new municipal development plan so hopefully it will remain I don’t see reason to take it away since has been successful but I would hold my breath on it because that depends on the particular kind of perspective or approach of the governments.

You must be clear about the expectations, other way people will be disappointed you can lie or miscommunicate this, we are here for this, and we are going to fall in love with the community, but you are not going to get married. Many of this communities had lost the ability to trust in initiatives like this because many others have not been clear about it, even if you say I’m here for your votes because the election is next year.