In the midst of Turkey’s efforts to prove itself as a leader in the Middle East, it has lagged behind the rest of the world in regards to climate change. Turkey was a late comer to the Kyoto Protocol, only becoming a member in 2009. Even then, there was a delay as they did not consider their new membership to come into effect until after the first commitment period ended in 2012. Climate change does not seem to be a high priority in Turkey – in fact, joining the Kyoto Protocol was seen in large part as politically necessary, especially in regards to its bid to join the EU. Yet, as with many countries, there are other interests that may pave the way for emissions reductions as co-benefits.

A 2009 report showed that Turkey’s emissions had risen 98% since 1990. For context, such a dramatic increase is more similar to high profile China and India with 186% and 152% respectively, than to the United States’ 6% increase. Yet even the US is seen as dragging its heels in regards to its target emissions reductions. By comparison, in 2009 the EU was 12% below its 1990 level.

Increasing Energy Demand

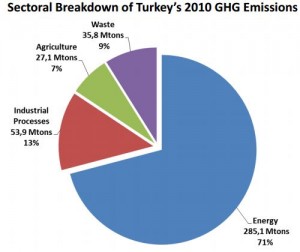

from Ministry of Environment and City Planning presentation

The doubling of Turkey’s emissions in the past two decades has been a result of major economic growth. The most significant factor in the increase has been energy, which contributes over 70% of Turkey’s total greenhouse gas emissions. The link between energy and the economy and fear that addressing climate concerns will “hinder competitiveness” are the main reasons why Turkey has not taken any significant action towards emissions reductions.

Though Turkey does not see GHG emissions as a reason to tackle their use of energy, it is concerned about its growing dependence on foreign imports. While many countries are now addressing this issue, Turkey’s increase in energy demand is particularly high. A 2011 BP world energy statistics report listed Turkey’s 2010 increase as 9.4% compared to an average of 3.5% for OECD countries and 7.5% for emerging economies. Most of the country’s energy demand is supplied by imports, with a dependency rate of 92% on oil and up to 98% on natural gas. As such, Turkey has placed energy supply security among its top priorities.

Energy Diversification

Moving towards energy independence does not automatically mean climate friendly production. One of Turkey’s front line attempts towards a local energy source is through coal. In January 2013, Turkey entered into a $12 billion agreement with Abu Dhabi to develop several power plants in southeast Turkey where lignite coal is plentiful (though as of August the future of this deal is uncertain). Yet there are also significant endeavors to increase Turkey’s energy production through renewable and sustainable means. Fatih Birol, the Chief Economist of the International Energy Agency who is himself a Turk, has highlighted the role of nuclear, solar, and wind power, all of which are now being addressed in Turkey.

The push for nuclear power is being driven by the government itself. Prime Minister Erdo?an foresees that nuclear power stations will reduce the need for natural gas imports by two-thirds. He hopes for as many as three nuclear plants, with agreements currently in place for two. However, the first is not even due to begin construction until 2019 so there will be no immediate effect of this government initiative, on either energy security or emissions reductions.

In the meantime, Turkey has turned to shale gas as a promising option. Over the past year there has been major activity regarding future shale gas usage, including a conference that hosted several energy firms. In June, the Energy Minister indicated that exploration is underway with the expectation that there are major reserves available, particularly in central Turkey but also in the southeast and Thrace regions. While fracking is currently contentious, many see it as a good transition fuel in comparison to the emissions of coal and oil. As Turkey continues to pursue shale gas as a local solution to its energy demands, there may be a parallel benefit of reduced energy emissions.

Finally, there are non-government sponsored forays in other renewable sources. Mostly backed by foreign investments, these do no constitute a concerted effort, yet they are exciting developments none-the-less. A 52 unit wind farm, the largest yet in Turkey, is currently underway as a joint endeavor between a Turkish and a German firm. GiraSolar is a US-Dutch firm that has been installing solar panel systems across Turkey, as well as investigating a 100MW solar energy plant. If built, this would be the largest solar plant in Europe. Finally, GE is building a new plant in south-central Turkey that will implement a new hybrid system, known as FlexEfficiency, that incorporates solar, wind, and natural gas. GE expects the plant to be 69% efficient, compared to typical natural gas efficiency of 30-50%.

While Turkey has shied away from pursuing climate change initiatives in deference to the economy, its new focus on energy security may be a back door for emissions reductions. While there is more that could be done to link the two, at present it is a step in the right direction that energy security and emissions reductions are not at odds with each other.