China has many reasons to celebrate the halfway mark of its twelfth Five Year Plan, implemented in 2011 with goals set for 2015. Serving as the economic and social development initiatives of the Communist Party of China, the Five Year Plan reflects upon the leadership’s priorities and ambitions. Such priorities range from Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward in the country’s Second Plan, originating from the leader’s pursuit of collectivization and heavy industry, which resulted in one of the world’s deadliest famines, to the current plan, which centers on reducing China’s reliance on exports and increasing the country’s domestic demand in order to ensure more stable, long-term growth.

One new development in China’s economic planning is the inclusion of energy and the environment, starting in 2005. The Maoist era emphasis on heavy industries such as steel and concrete, caused a spike in China’s energy intensity (the energy used to produce a unit of GDP). However, following China’s economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China’s energy intensity fell as Chinese factories switched from the energy intensive steel and concrete to the less energy demanding textile production. As China’s industrialization intensified in the 80’s and 90’s, a demand for heavy industry grew again until in 2002, energy intensity began to increase again. This development, along with issues of pollution and public health, greenhouse gas emissions, energy security, and Chinese participation in the Kyoto Protocol, nudged China’s leadership to take one of the largest initiatives in renewable energy.

What big developments has the twelfth Five Year Plan set? On the demand side, the Plan targeted a national 16% reduction in energy intensity and 17% reduction in CO2 intensity (ratio of CO2 per unit of GDP produced) by 2015 (compared with 2010 levels), instituting a range of targets on each province in relation to its production and consumption activities, placing higher quotas on the more developed eastern provinces and lower quotas on the more rural western ones. Furthermore, the National Development and Reform Commission has designated the seven cities and provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Guangdong, and Hubei to participate in a pilot carbon trading program, allowing firms to internalize their costs of carbon emissions and encouraging reductions where they are least costly. Finally, China hopes to increase its non-fossil fuel share in primary energy from 9.4% to 11.4% in 2015 and to 15% in 2020. Of this, most of the increased shares of electricity generation will be in hydro-electric, wind, solar, and biomass. While China is accused on the international stage of being the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gasses, it is also the world’s number one in terms of installed capacities of hydropower, wind, and solar water heaters.

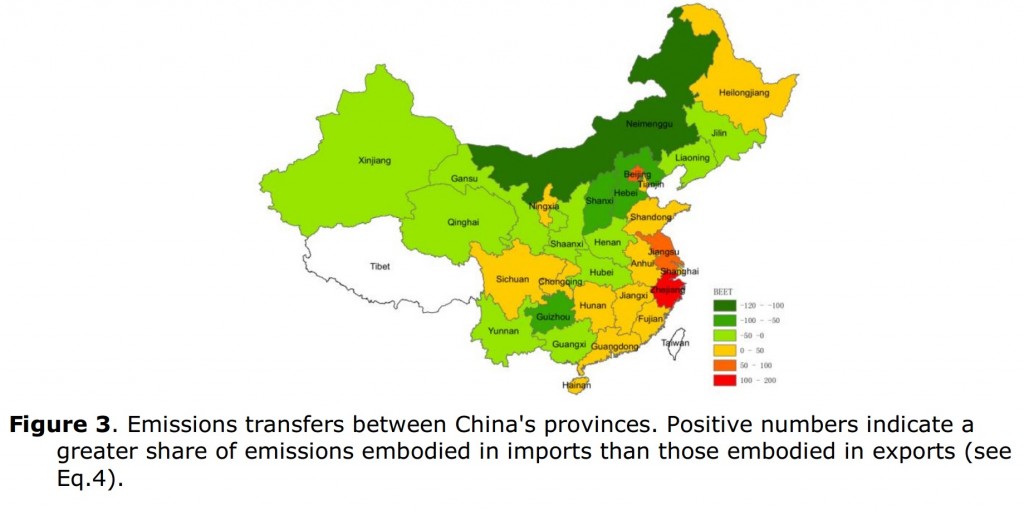

Unfortunately policy making is like the Greek hydra – for every solution we propose, two more problems arise. China’s method of determining provincial emission intensity reductions are based on political negotiations and might not necessarily take into account production-based emissions intensities or consumption-based emissions intensities. Production-based emissions intensity is as defined earlier, the territorial emissions to a unit of economic activity, while consumption-based emissions intensity adds the net import of emissions to the equation. In the case of China, many eastern provinces, such as Zhejiang and Jiangsu, import their goods from cheaper factories in central and western China, which would correspond to a higher consumption-based emissions intensity. In fact, while carbon emissions are highest in eastern China, the coast’s emissions intensities are the lowest, so enforcing higher quotas on the coastal provinces could shift emission production to the more inefficient central and western provinces.

The same possibility lies with a national carbon trading program. Furthermore, a criticism of China’s pilot emissions trading system is that industries will miss out on cheaper investment opportunities in nonparticipant regions, having to accept the more expensive abatement investment.

On the energy supply side, the future is just as unforeseeable. On the one hand, growth in wind power has exploded since the eleventh Five Year Plan, with actual electricity generation equaling 44.7 GW in 2010 (nearly nine times the target generation). Hydroelectric and solar also outperformed their 2010 targets. On the other hand, when taking hydroelectric power out of renewable’s energy share in China, the 2010 renewable energy percentage drops from 9.4% to 1.2%. Much of the existing renewable power is produced by China’s controversial dam projects. If a dam were to fail due to an earthquake, similar to Sichuan’s 2008 quake, the government might be forced to find alternative methods of energy production. This possible situation resembles Japan’s proposal to end its own nuclear production after the Fukushima disaster.

Finally, China’s current renewable production relies on an electrical grid that has not expanded enough to compensate for renewable energy’s growth. The percentage of on-grid wind capacity fell from 73.2% to 64.1% from 2006 to 2011. In 2011, photovoltaic’s on-grid capacity was 2.14 GW, much lower than the total installed capacity of 3.1 GW. Because of its late development, China’s grid system is neither flexible nor smart, making it difficult to integrate renewable energy into thermal production. Therefore, if China hopes to better achieve its goals in the twelfth Five Year Plan, it must address these issues to reassure the international community that it is serious on energy and climate change.