Maritime, aviation and land-based traffic due to trade and commerce and tourism compose the moving facade of international transport, one of the fastest growing sources for GHG emissions globally. In fact, though international transport describes the interaction of two or more economies, and cannot be traced back to a single set of physical boundaries, international transport was ranked sixth behind China, the United States, Japan, Russia, and Canada as a global source of GHG emissions in 2011 and 2012 according to the EDGAR database, moving from 1.04 to 1.06 Megatonnes of CO2 equivalent annually.

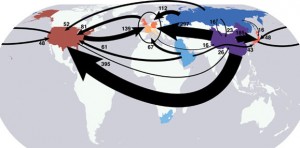

This map accompanying a study recently released by the Carnegie Institute displays the carbon supply chain in terms of net importers and exporters in a spectrum of red to blue, respectively:

Data collection on GHG emissions often avoid addressing international transport by tucking it into emission tallies for transport by sub-sector, or within counts for road, maritime, aviation, and rail. This is because it is difficult to quantify responsibility for emissions split between producing and consuming nations, especially between multiple stops and trading partners on an inter-regional supply chain. Only the International Transport Forum offers data on worldwide emissions from transport, and most of this takes the form of aggregate fuel usage statistics derived from International Energy Agency reports.

Disentangling the magnitude of emissions produced from transporting goods in international trade from production emissions can also prove troublesome. Especially in countries like China, India, and other countries that are net exporters of manufactured goods and agricultural products, goods made and packaged in-country now travel further than they ever have before, and many net importing countries do not factor emissions from production and transportation into their carbon budget. Recent attempts to investigate the relationship between territorial consumption emissions have uncovered that developed nations like the US and UK, where net emissions have reportedly decreased since 2005, import a lot of carbon-heavy goods, and stand to increase their budget substantially if imported carbon from these exports were included.

Emission Imports and Exports

In fact, a recent study conducted by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) took GHG emissions from Chinese goods exported to countries like the UK and the US in 2004 and subtracted this from China’s overall carbon budget, causing it to decrease by about 25%. According to the CCC report, total UK CO2 emissions have increased by about 10% since 1993 if imported or consumed emissions were factored into its total carbon budget. To its credit, the Chinese government has made progress in improving the energy efficiency of Chinese manufacturers by enforcing strict even eliminating tax breaks for companies exporting fuel-intensive products like pesticides, zinc, and silver according to a recent report released by the Worldwatch Institute.

Targeting corporate and consumer responsibility, especially in developed countries that are importing a lot of carbon-heavy goods, may be the key to correcting this imbalance. At the 2012 Earth Summit in Rio, the asymmetrical relationship between territorial and consumption emissions was attributed to the global race to the bottom that has occurred gradually over the past decade, as companies move production centers to developing countries with less stringent environmental standards than the EU or the United States. Carbon-footprint labeling could increase awareness at the consumer level, but what controls exist to correct this at a higher level in business and policy?

Solutions for Reducing Imported Emissions

Cristea, et al argue that a system for assessing the magnitude of emissions from good production and shipping is long overdue, and that it must address emissions by individual product, trade pairing, and position along the supply chain. Through a case study of international trade in 2004, researchers built a database of production output and transport emissions for all listed origin-destination trade flows occurring world-wide, and then calculated the contribution of international transport’s to total emissions, trends in GHG concentrations due to international trade flows, and changes in these patterns due to GDP variations, and tariff liberalization. Calculating the use of transport services occurs in a bottom-up fashion, and the use of transportation services by product type, trade flow, and mode of transport are expressed in kg/km.

Results for total emissions using this bottom-up method correspond to International Transport Forum calculations, and key findings include the differing values between source and destination emissions along the supply chain. Increased trade by itself does not lead to a substantial increase in worldwide emissions, but as trade shifts to distant trading partners, and centers of production move increasingly to China and India, use of air cargo and maritime shipping barges causes GHG emissions to increase 23 to 42 percent faster than trade. In addition, increases in emissions from aviation and maritime modes of shipping corresponded in part to tariff liberalization. Tariffs tend to favor proximate or regional trade pairings or clusters, which tend to rely on road or rail for shipping goods.

The findings of Cristea, et al echo the recommendations of the UN Framework on Climate Change in 1999 addressing international transport. The first recommendation consists of accurately allocating emissions due to the production and transport of goods to trading partners, and including them in each country’s GHG emission totals. The second includes approaching international transport as a distinct entity and linking it to patterns of carbon concentration and global trading schemes. The third recommendation rests in effectively applying taxes on carbon output and user fees on fuel consumption.

Balancing between reducing emissions and not imposing any negative impacts on trade does not have to be difficult- all of the above sources generally recommend moving away from fuel-intensive modes of transport like aviation shipping, for example. In the tug-of-war between rising economic powers like China and India, and well-established ones like the US and the EU, it will be interesting to see how recalculating GHG emissions totals inclusive of those coming from the consumption of exported goods will lead to lasting, equitable policy change.