The citizens of Austin, Texas have touted the capital as a “green city” and the city council adopted a Climate Protection Program in 2012 toward that end. One of the plan’s 5 major goals was to reduce energy use by 800 MW and increase Austin Energy’s renewable portfolio to 35% of its power mix by 2020. To meet this ambitious goal, Austin Energy has employed three strategies:

1) Implementation of a nationally-recognized green pricing program

2) Purchase power agreements for renewable energy installations in Texas

3) A robust solar rebate program

Before explaining these programs in depth, it is important to understand the quirkiness of Austin’s electricity market. Most electricity in and around the city limits is provided by one municipally owned utility (MOU), Austin Energy, whose management is accountable to the city manager and the city council – both of whom are accountable to the people of Austin. This model stands in stark contrast to most electric utilities in Texas, which have historically been Investor Owned Utilities (IOUs), meaning that their management is accountable instead to their shareholders.

Before the Texas electricity market was deregulated by the Texas Legislature in 2002, all electricity customers (rate payers) in Texas were served by one of the state’s many regional monopolies, both MOU and IOU. Thus, if you lived in Dallas, chances were that you paid your electric bill to the only IOU in the area- TXU. TXU owned and serviced everything from power plants and transmission lines to the meters going into your home and place of business. Before deregulation, TXU functioned similarly to the MOUs, CPS in San Antonio, and Austin Energy in Austin, except the rate payers had no say in the way TXU conducted its business. Texas Senate Bill 7 reformed this system by creating the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) to oversee the entire Texas grid, including reliability, operations and fair competition among the newly created Retail Electric Providers (REPS) who were now competing as “utilities” in previously IOU-dominated areas. While TXU was forced to compete for previously captive customers and significantly reduce its market share, MOUs were not subject to market deregulation, though they were still expected to connect to the Texas grid under ERCOT’s jurisdiction. In effect, Texas created one grid which operated under different market principles.

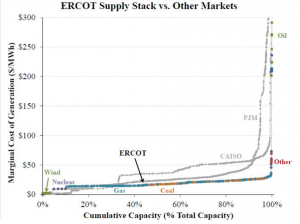

Today, ERCOT guarantees that the lights will stay on by providing a marketplace where utilities can buy and sell electricity from each other in a real-time spot market based upon supply and demand. As of 2010, Texas has 108,258 (MW) of installed electric capacity. Because it is highly unprofitable for utilities to fuel power plants without customers to buy the electricity they produce, many of these power plants do not run all the time, and others stay on only in times of high demand in case their power may be needed (known as “spinning reserves”). On a hot August day in Texas around 5 pm, it is not unheard of for ERCOT to anticipate loads above 63,000 MW as tired commuters come home and blast their air conditioners. Anticipating this demand, ERCOT will issue an auction the day before in order to meet this 63,000 MW target. The state comptroller’s website provides an excellent summary of this process: “Wholesale generation companies own the power-generating plants and sell electricity to the REPs; the transmission and distribution companies own the power lines the electricity flows through; and the retail segment comprises the REPs that sell electricity to end users.” These REPs begin by purchasing electricity with the lowest marginal cost of generation ($/MWHh) and will stop purchasing once they have reached 100% of anticipated capacity.

Source: Brattle Report (p. 18)

Because the ERCOT supply curve is based purely upon supply and demand without mandatory reserve margins (known as an Energy-Only market), it is dominated by low price resources like wind, nuclear, natural gas, and some coal which all cost less than $30/MWh. As the grid approaches peak demand though, prices can spike to as high as $3,000/MWh without warning. After the Enron debacle in 2001, these spikes are not usually caused by blatant market manipulations thanks to stricter federal regulations. Instead, most unplanned outages are the result of power plant maintenance or downed transmission lines from bad weather.

For eight years after deregulation, municipally owned utilities functioned outside of this Energy-Only market. Utilities like Austin Energy would generate what they needed for their customers and purchase anything above that margin from the ERCOT market as needed. Electricity rates were determined by the City Council. According to the Brattle Group (page 32): “[MOUs] do not require the same return on investment as [IOUs], because the costs of a generation investment are borne by their end-user customers regardless of prevailing market conditions. These entities engage in long-term planning for power supply and may directly invest in new generation projects or may sign long-term contracts to buy power from other generation owners.” But in 2010, ERCOT issued “Nodal” reforms which drastically changed this system. In the new system, rather than dispatching its own power plants to provide power to its own customers, Austin Energy now buys and sells all of its energy through ERCOT based upon the lowest-cost dispatch method discussed earlier. Thus, after 2010, any push for renewable energy within Austin Energy would now have to compete with other (usually cheaper) sources of electricity in the greater ERCOT market.

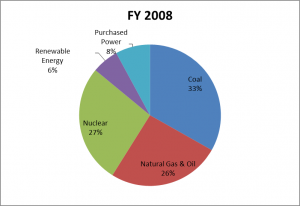

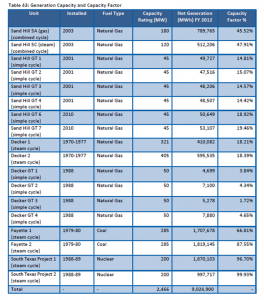

Austin’s Climate Protection program mandates that Austin Energy generate 35% of its total electricity from renewable energy sources by 2020. Austin Energy is working towards this goal through power-purchase agreements from generation facilities outside of Austin and through solar investment within the city. Here is what Austin Energy’s portfolio looked like in 2008 and 2012. (In the Appendix, I have added more detailed information about Austin’s power plants.)

The Green Choice program allows Austin Energy customers to voluntarily pay a renewable energy charge in place of the fuel charge for comparable energy generation facilities. This fund supports additional electricity production from renewable resources. According to NREL, Austin’s program is among the top in the nation and sells 744,443 Megawatt hours per year (MWh/year) to support 6% of Austin Energy’s load capacity.

According to Austin Energy’s 2012 Annual Report, 789 MW of installed renewable capacity came from Purchase Power Agreements (PPAs). They receive 100 MW from a biomass plant in Nacogdoches and 30 MW from the Webberville solar farm near Austin, but the remaining 630 MW originates from wind turbines in West Texas or near the Gulf Coast. This is driven by the lowest marginal cost deployment mechanism described in detail earlier. It is cheaper for Austin to purchase wind power from 500 miles away on the same grid than to produce the same amount of solar nearby.

Perhaps Austin’s most innovative program to encourage renewable generation closer to home is the “Value of Solar” pricing approach, which differs considerably from existing solar incentives. In Germany, the utility will pay a flat fee, known as a Feed-in-Tariff, to producers of solar electricity intended to lower the total cost of owning a system and thereby increase the number of systems within the country. The problem with Feed-in-Tariffs is that they artificially manipulate the price of solar electricity and can become top-heavy and expensive if too many people opt-in to the system. A federal Feed-in-Tariff is also a political non-starter in the United States. A more popular model in the US is known as net-metering. In a net-metering system, the energy produced by the solar PV array on the rate payer’s roof will be used before the energy from the electric grid. If the rate payer is not using much electricity but the sun is shining on a hot day, then any excess electricity produced will be sent back to the grid and the electric meter will literally run backwards. Instead of ever receiving a check from the utility for their power, consumers in a net-metering agreement will reduce their electric bills, sometimes to zero, and the PV system will pay for itself over time in reduced electric bills.

Austin’s Value of Solar is a one of a kind program because, due to the quirkiness of the ERCOT market, solar is worth different prices at different times and in different locations. As illustrated earlier, during times of peak demand, a REP may be willing to pay more for solar in an urban market in order to meet increased demand. Thus, solar power generated in the winter when demand is low may only be worth $30/MWh, while solar at 5:00 pm in the summer may be worth $50/MWh. Unlike net-metering, Value of Solar customers in Austin Energy will have two meters – one for energy coming in (consumed) from the ERCOT grid, and another tracking energy produced from the solar PV array which will feed into the ERCOT grid. In return for this solar power generated, the rate payer will receive a credit to their electric bill, similar to net metering. However, unlike net-metering, the amount that Austin energy credits the rate payer for solar is much higher than the price they originally paid for the electricity their system would have displaced in a net-metering system.

This Value of Solar concept was developed by Clean Power Research using a sophisticated system of algorithms taking into account loss savings, energy savings, generation capacity savings, fuel price hedge values, T&D capacity savings, and environmental benefits.

Rebate Amount ($) = PV Rating (kW dc – stc) x Inverter Efficiency (%) x Rebate Level ($/kWdc)

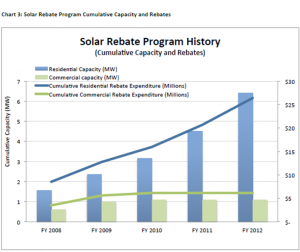

As of October 1, 2013, rate-payers in Austin who generate solar electricity will receive $0.128 in credit for every kilowatt hour that they produce from their systems. Compare this rate with the average electricity rates for Austin Energy at $0.098 per KWh and the average price of electricity in the state of Texas at $0.115 per KWh. As with any algorithm, there are considerable assumptions built into the model, such as an 8% reduction in capital costs for solar PV systems every year. Currently, a 6 KW PV system can cost about $13,000 to install before rebates and incentives (though most homeowners make money on them after 7 years) and because of this up front cost, distributed rooftop solar PV remains a niche market. Even after giving out over $25 million in solar rebates since 2008, the original 2.3 MW of rooftop solar in Austin has only increased to 8.3 MW in 2012.

There is considerable debate over the merits of the Value of Solar Tariff, but one issue which many installers and homeowners expressed at a recent Austin City Council Meeting, was the fear that the credits they were accruing from their PV systems would disappear at the end of the year. In its current implementation, any leftover credits accrued during the year will disappear on January 1, 2014. There is considerable discussion about moving the rollover date or simply abolishing it entirely. Alternatively, by allowing rate-payers to trade their unused credits on an open market (similar to carbon credits) or roll them into the Green Pricing Program, Austin Energy may finally find the perfect mix of financial incentives which could serve as the initial spark for an explosion of scalable, distributed solar PV in the US market.

Appendix:

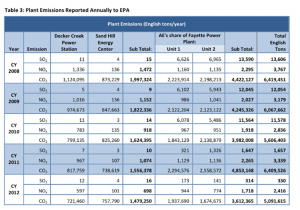

[All Tables come from the Austin Energy 2012 Annual Performance Report: http://www.austinenergy.com/About%20Us/Newsroom/Reports/2012AnnualPerformanceReport.pdf]

Leave a Reply