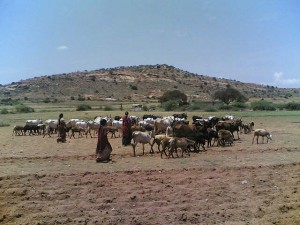

The process of implementing sustainable agricultural practices, that are in many cases cost effective and better for long-term production, is laden with countless financial, market, technical, political, and cultural barriers. Greenhouse gas mitigation in this sector will require change at the local level with small holder farmers as well as at the industrial level as large agribusiness companies will have to lead the way. The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) estimates that up to one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions come from agricultural production. Due to population growth trends, FAO projects that global agricultural production will have to increase by around 60% by 2050 to feed the world’s population. Overcoming barriers to agricultural GHG mitigation will only become more difficult and now is the time to act. Just what are a few of the barriers this sector faces?

Financial Barriers: (1) Developing world small holder farmers lack access to credit and other financial instruments to allow them to think beyond the upcoming growing season. As a result, large upfront investment costs will discourage them from adopting sustainable, GHG mitigating land practices. (2) Agricultural subsidies in both the developed and developing world for inputs (water, fertilizers, fuels, etc.) and outputs can distort the market and cause over or underproduction. As a result, we often see unsustainable farmland expansion and overuse of fertilizers and other inputs that have detrimental long-term environmental effects. Agricultural subsidies have doubled in Brazil in the past 4 years while those in India have also nearly doubled since 2005. Nearly $1.6 billion (90%) of Indonesia’s 2012 subsidies went to chemical fertilizer production. Not only do these subsidies stifle innovation and promote inefficient production, but they generally only help large-scale corporate agribusiness or fertilizer companies. Small holders are left out to dry.

Technical Barriers: (1) Because of education and governance constraints, there is a general lack of information access and trained human capital in most rural areas in the developing world. This prevents adoption of sustainable land management practices and results in little or no local production of inputs (fertilizers, pesticides, etc.) that comply with these sustainable practices. (2) There is limited technology transfer between developed and developing countries especially when the focus is not directly related to trade. As a result, national centers in developing countries are often unaware of or unable to implement methods that best suit their national needs and/or conditions.

Market Barriers: (1) The agriculture industry favors agrochemical companies and large industrial farm structures in places like Brazil, Indonesia, and China (the largest emitters). Investors in these areas are thus less likely to invest in what they perceive as riskier sustainable practices. (2) There is no carbon trading scheme for agriculture. A sophisticated carbon market for farmers could potentially make sustainable land management practices more profitable. However, corruption and governance issues will make this extremely difficult. The difficulties of implementing carbon trading even in the most developed countries is already apparent as seen with the weaknesses of the EU ETS.

Political Barriers: (1) Volatile policy and regulatory environments, in places like India and Indonesia, do little to promote agricultural practices that mitigate GHG emissions. Political decisions often give way to short-term pressures from special interest groups or industrial demands instead of long-term environmental planning strategies. For example, the Indonesian palm industry consistently exerts pressure on the president to prevent strengthening of the forest moratorium. (2) Fragmented federal systems make success in agricultural emissions reductions difficult in places like Brazil and India. India’s fragmented bureaucracy and regulatory system creates inconsistencies in data collection and policy implementation.

Cultural Barriers: (1) Smallholder farmers are in general more risk averse due to low capital, lack of credit, and poor investment opportunities. They may not be in a position to take on any unnecessary risk. This creates a psychological barrier to adopting unknown techniques. Uncertainty with respect to production, profitability, and implementation of conservation tillage and other sustainable land management practices are widespread. (2) Straw burning and slash and burn agriculture is less labor intensive and thereby more cost-effective than manually removing crop residue for small holders. Burning also can help control weeds and prevent blights and other plant diseases. Therefore, most developing country farmers favor burning as an effective way to manage and protect their production, as they are not immediately concerned with the long-term effects of this activity. Slash and burn is a huge problem in Indonesia with respect to palm production where there have been unconfirmed reports of large palm companies paying small farmers to burn peatlands with the goal of converting them to new palm plantations.

Cultural Barriers: (1) Smallholder farmers are in general more risk averse due to low capital, lack of credit, and poor investment opportunities. They may not be in a position to take on any unnecessary risk. This creates a psychological barrier to adopting unknown techniques. Uncertainty with respect to production, profitability, and implementation of conservation tillage and other sustainable land management practices are widespread. (2) Straw burning and slash and burn agriculture is less labor intensive and thereby more cost-effective than manually removing crop residue for small holders. Burning also can help control weeds and prevent blights and other plant diseases. Therefore, most developing country farmers favor burning as an effective way to manage and protect their production, as they are not immediately concerned with the long-term effects of this activity. Slash and burn is a huge problem in Indonesia with respect to palm production where there have been unconfirmed reports of large palm companies paying small farmers to burn peatlands with the goal of converting them to new palm plantations.

While this list is far from exhaustive, it represents some of the most important barriers that our team believes can be addressed. Part two of “Cultivating Sustainability” will focus on my colleagues’ and my recommendations on overcoming the above barriers.

Leave a Reply