Beginning with Deng Xiaoping’s reform programs, Chinese cities have competed for the designation as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). Categorization of a city or province as an SEZ ensured tax exemptions, foreign capital, and greater independence to trade, turning cities like Shenzhen, Xiamen, Tianjin, and Shanghai into the industrial powerhouses they are today. However, as China has developed more and more as both an industrialized nation and as a greenhouse gas emitter, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) announced in 2010 the Low-Carbon Cities China (LCCC) program. Included in this pilot program are the five provinces of Guangdong, Liaoning, Hubei, Shaanxi, and Yunnan, and the eight cities, Tianjin, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Xiamen, Hangzhou, Nanchang, Guiyang, and Baoding.

What exactly is the LCCC program? At its most basic, it is to accelerate China’s low carbon, economic growth in tandem with China’s 12th Five Year Plan’s energy goals:

- 16% reduction in energy intensity,

- 17% reduction in carbon intensity,

- And an increase in renewable energy to 11.4% of total energy production.

Each LCCC program participating local or provincial government must produce clearly established operational goals, major tasks, and specific measures of controlling local greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, participants are required to explore economic incentive policies, including carbon trading schemes, of which Shenzhen city and Guangdong province have already implemented and now rivals the European Union Emissions Trading System in size.

However, many of the participating cities’ proposed low-carbon development targets include only two factors, energy and carbon intensity. Both of these indicators function as ratios. Energy intensity is an indicator of energy efficiency and is calculated by dividing units of energy used by the local GDP. Carbon intensity, on the other hand, is the rate of emissions produced divided by local GDP. If units of GDP produced rise at a rate greater than a rise in emissions or energy use, then these indicators will project a rise in efficiencies, while total emissions and energy use have also accelerated, rather than decreased in total terms.

Another issue with the LCCC program has been pointed out by China experts: these energy/GDP and CO2/GDP indicators are macro-level indicators and do not necessarily reflect end-use energy or carbon intensities that can help direct local authorities towards appropriate action against their local, unique emission patterns. Of which, the China Energy Group identifies five micro sectors which when combined constitute all of the macro-level indicators:

- Residential Buildings (final energy/capita): This indicator should account for variable energy use due to differing climatic zones across cities. Cities in the north use much more energy for heat production during the winter than cities in the south.

- Commercial Buildings (m2): Energy demand varies greatly among commercial buildings types, including retail, office, hotels, schools, or hospitals.

- Industry (final energy/industrial share of city GDP): Different industry sub-sectors, cement, chemicals, and steel, exhibit different energy intensities.

- Transportation (final energy/capita): Transportation modes such as subways, light rail, and buses produce lower carbon intensities than private cars and taxis.

- Electric Power (CO2 emissions/electricity produced): Cities with more coal use in energy production have higher carbonization of electricity supply than those with more renewable, natural gas, and nuclear use.

- Fuel Consumption (CO2 emissions/fuel consumed): Fuel use varies among cities, with some making the transition to lower carbon natural gas while others rely on higher carbon coal.

In many cases, this data is nigh impossible to collect in the Chinese context. Statistics on staff size is more available than statistics on commercial buildings floor area. Industrial data is only available at the national level. Information collection of transportation use for every transportation mode is challenging.

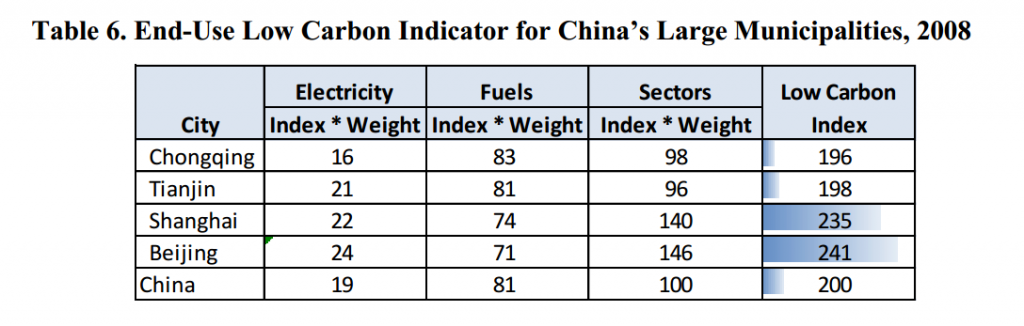

However, the China Energy Group compared these micro-level indicators among the four large municipalities in China, Chongqing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Beijing (the former two are members of the LCCC program while the latter two are not) and produced a “low carbon” index ranking for these cities, with a lower “low carbon index” value meaning a more “low carbon” ranking. Essentially, these results measure a city’s “low carbon” value with micro indicators based on population, rather than using ratios based on GDP.

The results of this study, which are of interest, is that the two municipalities in 2008 with the highest Low-Carbon Index, Shanghai and Beijing, did not become participants in the LCCC program. While China has extended its carbon trading schemes to both of these cities and this year’s smog apocalypse has promoted the emissions issue, perhaps full-fledged membership in the LCCC program might sponsor greater ambitions in reducing these cities’ carbon footprints.

Additionally, tools exist for the research, planning, and adoption of low-carbon development in Chinese cities and can help the design of clear, sector specific goals for LCCC program members. One product is the Benchmarking and Energy Saving Tool for Low Carbon Cities (BEST Cities), designed by the China Energy Group with support from the Energy Foundation China and the U.S. Department of Energy. The tool devises more than 70 different strategies for specific Chinese cities to reduce their energy use and carbon dioxide and methane emissions, by assessing energy use and emissions across nine sectors. Another such tool designed for the Chinese context is the World Resources Institute’s Greenhouse Gas Accounting Tool for Chinese Cities which covers five sectors and measures the six greenhouse gasses specified in the Kyoto Protocol. The use of these Low Carbon planning programs provides not only a scientific approach to emissions-reduction policy making, but also produces policy blueprints for replication by similarly situated cities.