As noted in part one of this series, the barriers to implementing sustainable land management practices, which are thoroughly outlined in our paper, are significant. But are they insurmountable? Our research and analysis tells us that though the road is long and difficult, there are actions that can be taken to put agricultural production on a more sustainable and climate-friendly trajectory. The implementation of many of these strategies requires developing country farmers (mostly smallholders) to bear uncertainty, risks and upfront costs. Thus the success of the interventions relies on influencing not only large companies and organizations, but also small farmer behavior, as they are the ultimate decision makers with respect to which mitigation options will be adopted.

As noted in part one of this series, the barriers to implementing sustainable land management practices, which are thoroughly outlined in our paper, are significant. But are they insurmountable? Our research and analysis tells us that though the road is long and difficult, there are actions that can be taken to put agricultural production on a more sustainable and climate-friendly trajectory. The implementation of many of these strategies requires developing country farmers (mostly smallholders) to bear uncertainty, risks and upfront costs. Thus the success of the interventions relies on influencing not only large companies and organizations, but also small farmer behavior, as they are the ultimate decision makers with respect to which mitigation options will be adopted.

Financial Recommendations: (1) To combat farm-level adoption constraints and short-term planning horizons, strengthening insurance offerings and microcredit could help overcome barriers. Expanding internationally supported credit and savings schemes and price supports for small farmers could assist rural populations manage the increased variability in their environment and farms that results from the adoption of new sustainable practices. (2) Reducing subsidies in developed and transition countries such as China and Brazil to reduce the use of fertilizers and limit the density of farm production is another effective strategy. Other incentive systems for developing countries could be implemented including subsidies for the adoption of sustainable land management technology transfers or practices that would otherwise be too expensive for farmers to adopt. (3) In more developed countries focus should be on large farmers and private organizations with greater influence on the agricultural commodity supply chains. Brazil has seen cautious success in this area with the 2006 Soy Moratorium.

Technical Recommendations: (1) Governments should invest more in agriculture technologies universities and support field research work of local professors to develop country-specific technical solutions. For instance, policies to reduce emissions from rice cultivation and fertilizers may be beneficial to China and Indonesia but will do little in Brazil where the majority of emissions comes from enteric fermentation and manure-related activities and only 5% comes from fertilizer use. (2) Governments should bolster institutional linkages between countries through agriculture and science ministries. Bilateral information and technology sharing through through organizations like FAO and USDA is one avenue of achieving this.

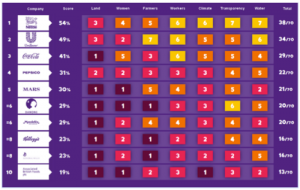

Market Recommendations: (1) To encourage private sector investment, governments of the technology providers  (i.e. U.S., EU) can propel technology transfer through domestic arrangements with the private sector, such as tax breaks and other measures. (2) Consumers and environmental advocacy groups should continue to put pressure on large companies targeting specific areas for improvement along the supply chain of global food and beverage, pinpointing policy weaknesses and celebrating improvements in social and environmental performance. For example, Oxfam’s “Behind the Brands” campaign examines the sourcing and supply chain policies of the ten largest food and beverage companies and pushes them to rethink their “business as usual.”

(i.e. U.S., EU) can propel technology transfer through domestic arrangements with the private sector, such as tax breaks and other measures. (2) Consumers and environmental advocacy groups should continue to put pressure on large companies targeting specific areas for improvement along the supply chain of global food and beverage, pinpointing policy weaknesses and celebrating improvements in social and environmental performance. For example, Oxfam’s “Behind the Brands” campaign examines the sourcing and supply chain policies of the ten largest food and beverage companies and pushes them to rethink their “business as usual.”

Political Recommendations: This is perhaps the most difficult area to influence but we have still included some general recommendations. (1) Improving transparency through independent information collection and monitoring can allow for better coordination and policy evaluation. Brazil has seen success in the forestry area using independently developed landsat technology and Indonesia is currently experimenting with WRI and other private organizations to develop land mapping and monitoring technology. (2) As national level policy will be more concerned with maintaining food security, it should use investments in abatement activities as an incentive to encourage policy conformity. These abatement incentives would include technology transfers as well as co-benefits such as increasing productivity and decreasing soil degradation. In countries like China where decision-making is centralized, this can mean very quick policy changes to adopt these practices.

The cultural barriers described in the previous installment of this series are by nature persistent overtime and slow to change. Influencing small farmers to think long-term can only be accomplished through short-term actions that prove effectiveness and profitability. The above recommendations will do this over time. As before, this list is neither complete nor exhaustive. However, it represents starting points that can and should be pursued to put agricultural development, which is expected to grow rapidly, on a different trajectory.