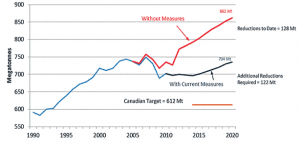

As a whole, Canadians are acutely aware of the dangers posed by climate change. The governments of Canada’s ten provinces and three territories are working to strengthen their individual efforts and mitigate their contribution to the country’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Environment Canada, the lead federal agency on greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions, notes that the federal government is taking a sector-by-sector approach to the issue and has already implemented regulations in two of the sectors with the highest levels of emissions: transportation and electricity. Also, Canada remains a Party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and is committed to reducing its emissions to 17% below 2005 levels by 2020 under the non-binding Copenhagen Accord (which Canada signed onto in December 2009).

However, the remaining 122 Mt emissions gap Canada must fill in order to meet its 2020 target, couple with stalled progress at the federal level on the release of its long-promised oil and gas regulations, have led many to question the federal government’s continued commitment to climate change mitigation efforts. Compounding the issue is Canada’s decision to formally withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol in 2011, which relieved the country of any binding obligations to reduce its GHG emissions. Existing concerns regarding Canada’s recent lackluster federal climate policy were exacerbated by Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s statement of support for the Australian government’s plan to repeal its carbon tax. This absence of action on federal climate change policy resulted in Canada ranking near the bottom of the most recent Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI), an instrument that compares the climate protection performance of the world’s top 58 emitting countries.

Source: Environment Canada, 2013

Conversely, the preceding setbacks at the federal level were partially counterbalanced in 2013 by actions taken by Canada’s provinces. Several recent climate policy achievements made at the provincial level include the rollout of Quebec’s cap-and-trade system; Ontario’s phase-out of coal-fired thermal activity; British Columbia’s decision to keep its carbon tax after undergoing thorough review in 2012; Alberta’s plan to raise its fine for heavy emitters after its Specified Gas Emitters Regulation (SGER) expires in September 2014; and, Saskatchewan’s ongoing plans to adopt SGER-style regulations in 2015. These successes are particularly notable given the fact that the provinces above have the highest GHG emissions levels of all of Canada’s provinces (Alberta and Ontario top the list at 249.3 MtCO2e/36% of total emissions, and 166.9 MtCO2e/24% of total emissions, respectively).

Despite these advancements, however, experts predict that Canada will fail to meet its 2020 emissions reduction goal without swift regulatory action aimed at reducing emissions from the oil and gas sector. Moreover, Canada’s electricity and transportation sectors are projected to continue to produce a large portion of the country’s total GHG emissions.

While not nearly as effective as a national carbon tax or cap-and-trade system, a multi-level approach will be essential to ensuring continued progress in Canada’s efforts to reduce its GHG emissions. The federal government would ideally spearhead this effort by targeting the geographical areas and sectors with the highest levels of GHG emissions, thus reinforcing Canada’s collective commitment to combatting climate change. However, the economic benefits afforded by the oil and gas sector, as well as the inherent fragmentation of Canada’s provincial policies, are likely to continue to serve as obstacles to achieving progress in this area. Given these challenges, Canada’s approach to reducing its GHG emissions is likely to remain uncertain over the coming months.