The National Climate Change Strategy published in 2010 cites long term goals of at 30% of renewable energy in the total electricity production by 2023. (By 2012, the share of installed capacity was increased to 39%. but there is still much growth necessary to meet the intended 2030 total generation capacity.) Such a scenario would include the full potential of hydro power (up to 40,000 MW), 20,000 MW of wind generation, and 600 MW from geothermal production. Solar energy is also noted as a promising source. The Strategy anticipates that this proposed share of renewable energy would reduce BAU electricity generation emissions by 7%.

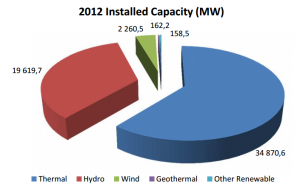

Figure 1: The World Bank’s 2013 Assessment of Turkey’s Renewables

The Turkish government has been strongly promoting nuclear energy while renewable energy, such as wind, geothermal, wind, and solar, are left for private and foreign investors to take advantage of. In order to make renewable energy investments more appealing, Turkey passed a 2005 law which ensured that any renewable energy produced would be incorporated into the electricity grid with a feed-in tariff (FIT). However, due to a flat purchase rate across all renewable sources, as well as a rise in the standard energy price as compared to the tariff, this 2005 scheme has not generated as much buy-in as was anticipated.

A 2011 revision of the renewable energy law established an updated Renewable Energy Support Mechanism for investors. Two key revisions were FIT prices that varied by the type of renewable and a more consistent, predictable market system that eliminates the issue of price competition. Other benefits include exemption from fees and taxes. Turkey hopes that these incentives will attract more investors to jump start the renewable industry.

Among the renewable sources, Turkey’s hydropower has benefited the most from investments. By the beginning of 2012, hydropower licenses were established for a capacity of approximately 30,000 MW. Half of these licenses were operational, the other half were under construction.

Wind power farms have also been attractive to investors. On November 1st, 2007, the day license applications were accepted, total proposed capacity was about 80 GW (twice Turkey’s total generation capacity in 2007). After serious considerations of how to judge applications as well as remain within the limited wind transmission capacity, licenses were first awarded in December 2010. By 2012, the licensed capacity was roughly 7500 MW, with 1700 MW in operation and 5,800 MW under construction.

There is huge potential for solar power in Turkey. That said, the licensing process in only just beginning, as solar energy was not a viable commercial enerprise until the 2011 revisions in the Support Mechanism. Having learned from the debilitating influx of wind license applications, a cap of 600 MW has been placed on 2013 solar licenses. Des

pite the slow beginning while Turkey irons out its regulatory system, a total of 3000 MW is anticipated by 2023.

Due to the unique geological make up in Turkey, its geothermal resources are greater than any other European country. The projected capacity is 2000 MW. That said, in 2012 only seventeen licenses had been awarded for 369 MW. Of this, 114 MW was operational with another 255 MW under construction.

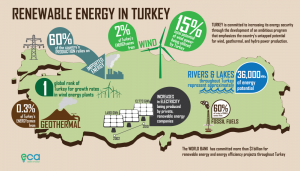

Figure 2: Turkey’s Energy Production (thermal includes natural gas and fossil fuels)

Figure 2: Turkey’s Energy Production (thermal includes natural gas and fossil fuels)

Leave a Reply