By 2030, The Economist projects 1 billion Chinese, or 70 percent of the population, will live in urban centers compared to 50 percent in 2014. This presents a great challenge to the cause. In an effort to spread out the growth, Beijing has plans to move upwards of 5 million residents to neighboring Hebei Province, aiming to cap population to 18 million by 2020.

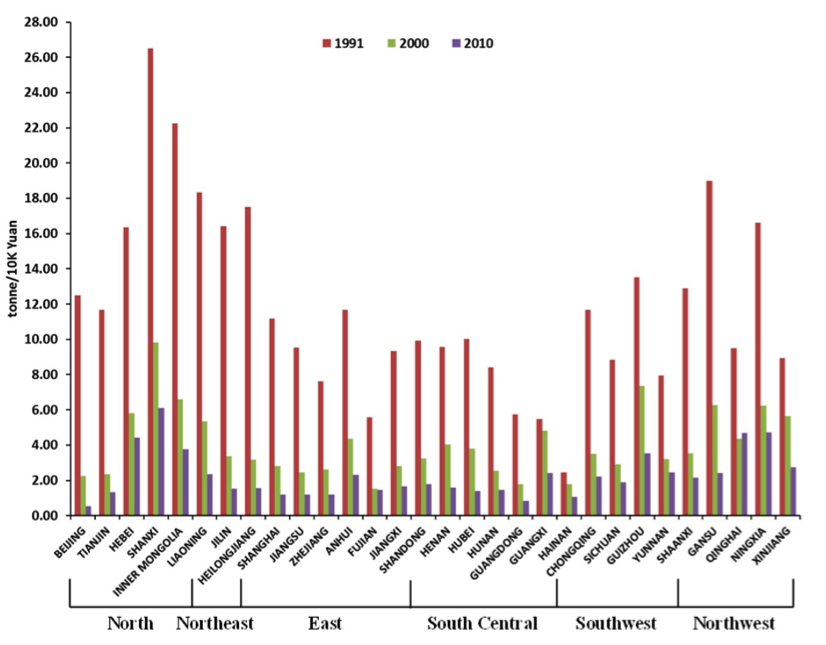

As the figure below illustrates, northern and northeastern provinces have the highest share of GHG emissions. However, time series analysis reveals that the gap is closing. While in 1991 the difference was significant, we are now seeing some northwestern provinces; particularly Gansu, Liaoning, Ningxia and Xinjiang emissions levels are on par with Shaanxi province (the historically highest emitter of GHG).

Figure: Time Lapse of GHG Emissions, by Province, 1991-2010

Source: Paper for Agricultural & Applied Economics Association, 2013

Any plans to reduce GHG emissions must take these trends into consideration. Opportunities lie in learning from the experiences from the east and establishing less polluting plants, more efficient buildings and greater public education to counter the potentially disastrous effects of emissions potential.

Although the bulk of our analysis in the China country paper focused on the power and the iron and steel industries, it is important to highlight two other sectors that will play a pivotal role in the reduction of GHG emissions in China, they are: transport and buildings. Both sectors relate heavily to end-user and consumer behavior and benefit from more stringent industry standards as well as greater incentives and education of the general public.

Transport

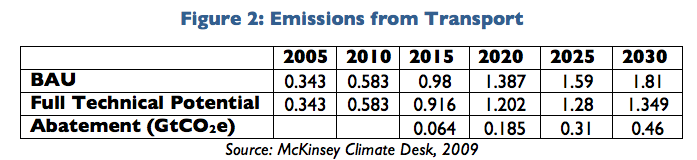

In 2009, China’s transport sector emissions climbed to over 470 MtCO2e, more than double China’s transport emissions a decade before.

However, great strides in policy have been made to address transport emissions. In September 2013, the State Council released the “Action Plan for Air Pollution Prevention and Control” in response to the dangerous levels of smog. As part of the action plan, fuel standards were set by region, with the strictest standards for Shanghai and Beijing. Additionally, subsidies have been provided for the adoption of hybrid vehicles or to incentivize the use of public transportation, while some regions have promoted the use of liquefied natural gas (LNG) vehicles.[2]

Urbanization and spatial geography will play a key role in the transport sector. “You can almost see the end game,” states McKinsey China Director Jonathan Woetzel. According to Woetzel, the Chinese population will gravitate towards existing urban centers such that current cities will become bigger hubs with populations ranging between 10-50 million people, akin to Western Europe. As a result, rail transportation will become increasingly important, with emphasis on the 35 major cities in the next 10 years.

Within urban centers, in addition to growing existing municipal policy to curb personal vehicle use and increased fuel efficiency, investing in public transportation infrastructure will be key to GHG mitigation action. This is something we see happening in Beijing and Shanghai. But in anticipation of these growing hubs, public transportation will be increasingly important in growing second and third-tier countries. While historically policies have been reactionary (such as Beijing limiting the number of cars on the road during danger levels of air pollution), it’s time to become more forward thinking. The costs of damage control are beginning to greatly outweigh preventative measures.

For more detailed analysis of what can be done in the transport sector, refer to “The High Cost of Mobility: Reducing GHG Emissions from Transport” paper. The paper details a three-pronged approach to reducing GHG emissions in China which include:

Avoid: Determine more sustainable and equitable ways to limit demand for light-duty vehicle travel, such as distance fees.

Shift: Continue to explore using fiscal incentives, like tax breaks, to promote the use of electric vehicles and alternative fuel technology and plug-in infrastructure.

Improve: Encourage partnerships between domestic and international vehicle manufacturers, to accelerate diffusion of clean technology.

Buildings

As rural regions develop, the building sector will become increasingly important in the abatement of GHG emissions. China is, according to McKinsey, the “single biggest build out of infrastructure in the history of mankind… spending more as a share of GDP (approximately 8.5% annually) in the last 15 years and in absolute numbers; the market is clearly still going.” Urbanization will be the key issue in the coming decades. Infrastructure productivity is still lacking in China; experts liken it to western standards of the 1940s and 50s. Anticipating cities to grow and greater densification of clusters, “China still has 40-50 years of infrastructure productivity to catch up.” With the majority of the population slated to live in these mega urban centers, challenge will be to strike the perfect balance between productivity, improved urban quality of life and environmental soundness.

Although building emissions fell in the early 90’s due to improvements in heating infrastructure, since then, building emissions have been on the rise. Current Chinese building sector emissions stand at 1.343 GtCO2e (share of total) and are expected to rise to 2.443 GtCO2 by 2030 without abatement measures (project share of total). According to the Climate Policy Initiative, as of 2009, commercial and public service buildings accounted for 70% of sector emissions while residential buildings accounted for 30%.

Chinese policymakers are aware of this potential problem and are addressing it with a variety of policies ranging from heating restrictions, labeling of energy efficient household electronics to building standards for both residential and commercial properties. In Beijing, local communities are encouraging change in user behavior by providing free energy-saving light bulbs to allow users to experience the cost-savings from the simple switch.

China is a “cross the river by feeling the stones” country. Often employing pilot programs to test new strategies and policies before deciding whether to scale-up, the concept of “low carbon cities” is becoming more important. However, the current barriers exist in the measurement of achievements. Despite having commissioned several research firms to develop citywide emissions inventories, the buildings industry lacks a common methodology – an issue that resonates worldwide. A greater push for standardization of measurements will be the first step towards methodical abatement in this sector.

Tackling emissions in the buildings sector will require more stringent industry-wide standards and will also require changing consumer behavior. This will necessitate tremendous amounts of public education; similar to what the US has been experiencing since the 1980s. Now is the perfect time for the Chinese government to leverage the recent tangible costs (strange weather, dense smog, public health concerns) to educate and push for end-user behavioral changes which will make a noticeable difference in the fight against climate change.